A SON OF THE SAHARA

BY

LOUISE GERARD

PREFACE

A beach of white sand, the whisper of palms answering the murmuring moonlit sea, the fragrance of orange blossoms, the perfume of roses and syringa,—that is Grand Canary, a bit of Heaven dropped into the Atlantic; overlooked by writers and painters in general. Surely one can be pardoned a bit of praise and promise for this story, laid, as it is in part, in that magic island.

The Canaries properly belong to the African continent. That is best proven by their original inhabitants who were of pure Berber stock. The islands are the stepping stone between Europe and the Sahara. Mysterious Arabs and a continual stream of those silent men who come and go from the great desert tarry there for a while, giving color and romance to the big hotels.

The petty gossip, the real news of the Sahara "breaks" there.—Weird, passionate tales; believable or not, they carry an undercurrent of reality that thrills.

From such a source came this story. Unaltered in fact, it is given to you, the life story of a man and a woman who turned their backs on worldly conventions that they might find happiness. If it is frank, forgive it. Life near the Equator is not a milk and water affair.

THE PUBLISHERS.

With Annette limp across his saddle, Casim Ammeh sped away.

PART I

A Son of the Sahara

CHAPTER I

In the days when France was pursuing a vigorous forward policy in Africa, a policy started by General Faidherbe and carried on by subsequent governors, one of the bravest among her pioneer soldiers was Colonel Raoul Le Breton.

He was a big, handsome man with a swarthy complexion, coal-black hair and dark, fiery eyes, by nature impetuous and reckless. With a trio of white sergeants and a hundred Senegalese soldiers, he would attempt—and accomplish—things that no man with ten times his following would have attempted.

But there came a day when even his luck failed.

He left St. Louis, in Senegal, and went upwards to the north-east, intending to pierce the heart of the Sahara. From that expedition, however, he never returned. The Government at St. Louis assumed that he and his little pioneer force had been wiped out by some hostile negro king or Arab chief. It was but one of the tragedies attached to extending a nation's territory.

When Raoul Le Breton went on that ill-fated expedition, he did what no man should have done who attempts to explore the Back of Beyond with an indifferent force.

He took his wife with him.

There was some excuse for this piece of folly. He was newly married. He adored his wife, and she worshipped him, and refused to let him go unless she went also.

She was barely half his age; a girl just fresh from a convent school, whom he had met and married in Paris during his last leave.

Colonel Le Breton journeyed for weeks through an arid country, an almost trackless expanse of poor grass and stunted scrub, until he reached the edge of the Sahara.

Annette Le Breton enjoyed her travels. She did not mind the life in tents, the rough jolting of her camel, the poor food, the heat, the flies; she minded nothing so long as she was with her husband. He was a man of rare fascination, as many women had found to their cost; a light lover until Annette had come into his life and captured his straying heart once and for all.

On the edge of the Sahara Le Breton met a man who, on the surface at least, appeared to see even more quickly than the majority of negro kings and Arab chiefs he had come in contact with, the advantages attached to being under the shadow of the French flag.

It would be difficult to say where the Sultan Casim Ammeh came from. He appeared one afternoon riding like a madman out of the blazing distance; a picturesque figure in his flowing white burnoose, sitting his black stallion like a centaur.

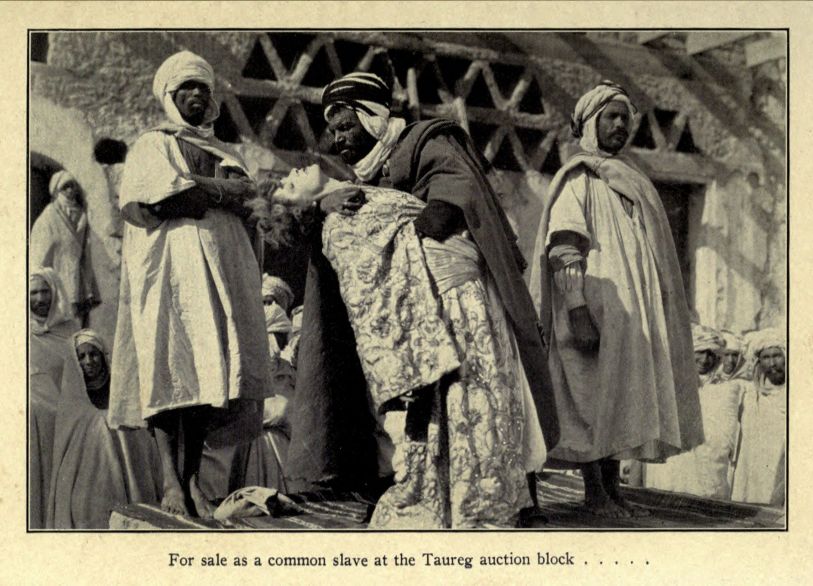

He was a young man, perhaps about twenty-four, of medium height, lean and lithe and brown, with fierce black eyes and a cruel mouth: the hereditary ruler of that portion of the Sahara. His capital was a walled city that, so far, had not been visited by any European. In his way he was a man of great wealth, and he added to that wealth by frequent marauding expeditions and slave-dealing.

With a slight smile he listened to all the Frenchman had to say. Already he had heard of France—a great Power, creeping slowly onwards—and he wondered whether he was strong enough to oppose it, or whether the wiser plan might not be just to rest secure under the shadow of its distant wing, and under its protection continue his wild, marauding life as usual.

As he sat with Colonel Le Breton in the latter's tent, something happened which caused the Sultan Casim Ammeh to make up his mind very quickly.

It was late afternoon. From the open flap of the tent an endless, rolling expense of sand showed, with here and there a knot of coarse, twisted grass, a dwarfed shrub, or a flare of red-flowered, distorted cacti. The French officer's camp was pitched by an oasis; a little group of date palms, where a spring bubbled among brown rocks, bringing an abundance of grass and herbs where horses and camels browsed.

As the two men sat talking, a soft voice said unexpectedly:

"Oh, Raoul, I'd no idea you had a visitor!"

All at once a girl had appeared in the entrance of the tent She was small and slim, with two thick plaits of golden-brown hair reaching to her knees; a beautiful girl of about eighteen, with wide grey eyes and a creamy white skin.

Her voice brought Le Breton to his feet.

"What is it, Annette?" he asked.

"I thought——I'll come later," she said; the blushes mounting to her cheeks.

The Sultan Casim Ammeh got to his feet also. Not out of any sense of deference; he had none where women were concerned, but drawn there by the beauty of the girl.

"You needn't mind what you say in front of this man," her husband remarked. "He doesn't understand a word of French.

"Ill tell you later, Raoul, when there's nobody here." She would have gone, but Le Breton called her forward and, in Arabic, introduced her to his visitor.

Annette bowed to the lean, lithe, brown man in the white burnoose, and her eyes dropped under the fierce admiration in his.

The Sultan looked at her, all the time wondering why the white man was such a fool as to let this priceless pearl, this jewel among women, go unveiled, and allow the eyes of strange men to rest upon her with desire and longing.

Annette said she was pleased to meet him: a message her husband translated, and which brought a fierce smile to the young Sultan's face and made the wild desire in his savage heart suddenly blossom into plans.

So she, this houri from Paradise, was pleased to meet him! This fair flower from a far land! But not so pleased as he was to meet her.

And her husband let her say such things to strange men! What a fool the man was! Not worthy of this houri! He could not appreciate the treasure he possessed. Not as he, the Sultan, would, were she his.

Casim Ammeh despised Colonel Le Breton utterly.

As soon as the introduction was over, Annette would have gone.

"Don't run away, my pet," her husband said fondly. "I shall soon have finished."

But the girl went, anxious to get away from the Arab chief who watched her with such covetous desire and smouldering passion in his fierce black eyes.

When she had gone, the two men seated themselves again. But the Sultan gave no thought to the business in hand. He only wanted one thing now—the girl who had just gone from the tent.

Soon after Annette's departure he left, promising to visit Le Breton again within the course of a few days.

He kept his word.

Five days later he swept out of the desert with a horde of wild horsemen. And in less than half an hour there was only one of Raoul Le Breton's ill-fated expedition left alive.

The next day, with Annette limp across his saddle, the Sultan Casim Ammeh set off with his following to his desert stronghold.

CHAPTER II

The city of El-Ammeh lies about a hundred miles within the Sahara proper. It is a walled town of Moorish aspect, built of brown rock and baked mud. Within the walls is a tangle of narrow, twisted, squalid lanes—a jumble of flat-roofed houses, practically devoid of windows on the sides overlooking the streets. Here and there a minaret towers, and glimpses of strange trees can be seen peeping over walled gardens.

Along one side stands a domed palace; a straggling place, with horse-shoe arches, stone galleries and terraces. In front of it a blue lake spreads, surrounded by fertile gardens and groves of fruit trees. And the whole is encircled by the desert.

Annette Le Breton remembered nothing of her journey to El-Ammeh. Her life was a nightmare of horror that held nothing but her husband's murderer, whom she could not escape from. She was taken to the palace, and placed in the apartment reserved for the Sultan's favourite. A big room with walls and floor of gold mosaic, furnished with ottomans, rugs and cushions, and little tables and stools of carved sandalwood inlaid with ivory and silver.

On one side of the apartment a series of archways opened on a screened and fretted gallery, at the end of which a flight of wide, shallow steps led down into a walled garden, a dream of roses.

But it was weeks before Annette knew anything of this.

All day long she lay, broken and suffering, on one of the ottomans, and dark-faced women fawned upon her, saying words she could not understand; women who looked at her queerly, jealously, and talked about her among themselves.

A strange girl, this new fancy of the Sultan's! Who wanted none of the things he piled upon her—not even his love. A girl who looked as though life were a mirage; as if she moved in bad dreams,—a listless girl, beautiful beyond any yet seen in the harem, who seemed to have neither idea nor appreciation of the honour that was hers; who lay all day in silence, her only language tears. Tears that even the Sultan could not charm away.

In fact they seemed to fall more quickly and hopelessly when he came to see her.

Yet he did everything that mortal man could do to comfort her.

Jewels were showered upon her; jewels she refused to wear, to look at even; casting them from her with weak, angry hands, when her women would have decked her with them for her master's coming.

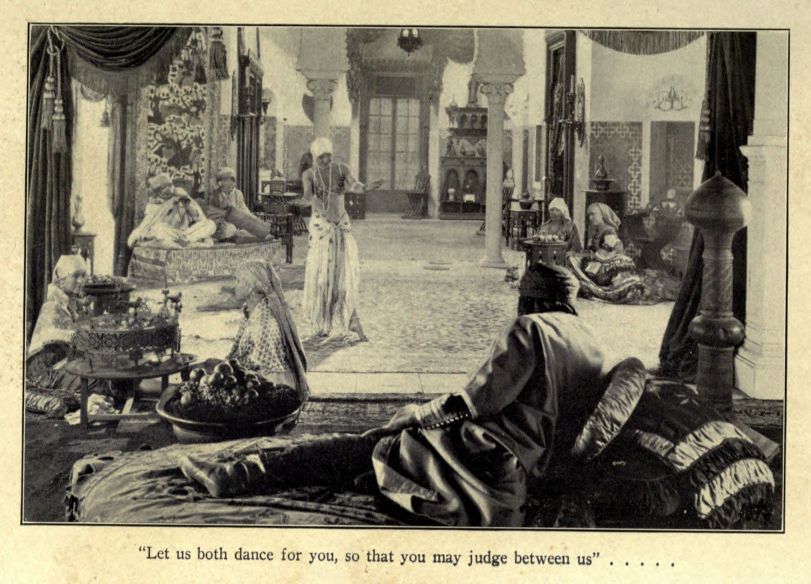

And never before were so many musicians, singers, dancers, and conjurors sent to the women's apartments. Hardly a day passed without bringing some such form of diversion; or merchants with rare silks, perfumes and ostrich feathers. The harem had never had such a perpetual round of amusements.

All for this new slave-girl. And she refused to be either amused or interested. She would look neither at the goods nor the entertainers. She just stayed with her face turned towards the wall and wept.

One day when the Sultan came to the harem to visit his new favourite, some of the older women drew him aside and whispered with him.

They suspected they had found a reason for the girl's strange behaviour.

Their words sent the Sultan from the big hall of the harem to the gilded chamber set aside for Annette, with hope in his savage heart, and left him looking down at her with a touch of tenderness on his cruel face.

He laid a dark hand on the girl, caressing her fondly.

"Give me a son, my pearl," he whispered. "Then my cup will be full indeed."

Annette shuddered at his touch.

She had no idea what he said. He and his language were beyond her.

As the long weeks ground out their slow and dreary course, Annette grew to suspect what her attendants now knew.

The weeks became months and Annette languished in her captor's palace; her only respite the times he was away on some marauding expedition. He loved rapine and murder, and was never happy unless dabbling in blood. Sometimes he was away for weeks together, killing and stealing, bringing slaves for the slave-market of his city, and fresh women for his harem.

During one of his absences Annette's baby arrived.

The child came a week or so before the women had expected it.

"The girl has wept so much," they said, "that her son has come before his time, to see what his mother's tears are about. And now, if Allah is kind, let us hope the child will dry them."

For a fortnight Annette was too ill to know even that she had a son.

When the baby was brought to her, she hardly dared look at it, not knowing what horror might have come from those ghastly nights spent with the Sultan Casim Ammeh.

But when she looked, it was not his face, dark and cruel, that looked back at her.

In miniature, she saw the face of Raoul Le Breton!

This son of hers did not owe his life to the Sultan. He was a legacy from her murdered husband. Something that belonged to her lost life.

With a wild sob of joy, Annette held out weak arms for her baby. Weeping she strained the mite to her breast, baptizing it with her tears. Tears of happiness this time.

Light and love had come into her life again. For Raoul was not dead. He had come back to her. Weak and tiny he lay upon her heart, hers to love and cherish.

She was lying on her couch one day, too absorbed in tracing out each one of her dead lover's features in the tiny face pillowed on her breast, to notice what was happening, when the voice she dreaded said in a fierce, fond manner:

"So, Pearl of my Heart, you love my son, even if you hate me."

Annette did not know what the Sultan said. But she held her child closer, watching its father's murderer with fear and loathing; afraid that he might put his dark, defiling hands upon her treasure.

But he did not attempt to touch either her or the child.

Seating himself at her side, he stayed watching her, tenderness on his cruel face, for the first time having pity on her weakness. The weakness of the woman who had given him the one thing his savage heart craved for, and which, until now, had been denied him—a son.

CHAPTER III

By the time Annette knew enough Arabic to make herself understood, and to understand what was said around her, she realized that if the Sultan learnt her boy was not his, this one joy of her tragic life would be taken from her. He would murder the son as he had murdered the father.

As the baby grew, her one idea was to keep its true parentage from her savage captor. If she could have done so, she would have kept his dark, blood-stained hands from touching her son. But this was impossible. When in El-Ammeh, the Sultan came every day to see the child, often sitting with it in his arms, watching it with an air of proud possession.

And fearsomely Annette would watch him, wondering why he never suspected. But he was too eaten up with his own desire for a son ever to give a thought to her dead husband.

The baby was given the name of Casim Ammeh. But Annette always called her boy by another name, "Raoul Le Breton."

And at the age of five he said to her:

"Why do you always call me 'Raoul,' not 'Casim,' as my father does?"

His father!

Annette's heart ached. His father had been dead these long years, murdered by the man her son now called by that name.

"The Sultan and myself are of different races," she said. "He calls you by his name. I, by one of my own choosing, Raoul Le Breton.'"

"Why do you always say 'the Sultan,' and never 'your father'?"

Sadly she smiled at her small questioner.

"Some day, my son, I'll tell you. When you are a man and understand things."

At five, Raoul Le Breton was a big, handsome boy, spoilt and pampered by the whole harem, and spoilt most of all by the man he proudly called "Father."

The Sultan in his flowing white robes, with his half-tamed horses, his horde of wild followers and barbaric splendour, was a picturesque figure, one to capture any brave boy's heart.

Annette did all she could to counteract her captor's influence, but, as the child grew, he was more with the Sultan than with her. What was more, he craved for men's company.

He soon tired of the amusements the harem could offer. He much preferred to be on his own horse, galloping with the Sultan or some of his men along the desert tracks about the city. And knowing Annette loved her son, and hated him, despite their years together, the Sultan did all he could to win the boy's affection and wean him from his mother.

He might have succeeded, except for one thing. The boy loved learning, and to hear of the great world that his mother came from; a world that seemed as remote from El-Ammeh as the paradise his Moslem teachers spoke of.

The Sultan was not averse to the mother teaching her son. He was a shrewd man, if savage and cruel. And that France from where the girl came was growing ever more powerful. It would be to the boy's advantage to learn all the arts and cunning of his mother's people.

The Sultan Casim gave Annette but one present that she took from him willingly; a sandalwood bureau with shelves and drawers and little sliding panels, an elaborately carved and handsome piece of furniture; stocked with slate and pencil, paper, quills and ink—such as the priests at the mosques used themselves. For this strange girl who hated him had more learning than all the priests put together.

But, for all that, the youngster had to sit at their feet at appointed times, and be taught all the Sultan had ever been taught, to read and write, and recite scraps from the Koran, and to be a true Moslem.

Annette hated this wild, profligate religion, and into her son she tried to instil her own Roman Catholic faith.

But at eight years, although he learnt with avidity all her other teachings, he laughed at her religion.

"Yours is a woman's religion, little mother," he said one day. "It's all right for you—a religion that prays to a woman, but it is not suitable for men. Give me my father's religion. A religion where men rule. In that, one does not bow the knee to a woman. A good religion, my father's, fierce and strong, of love and fighting, not a puling thing where one prays to a woman and a babe. No, little mother, keep your religion, and be happy with it. I prefer my father's and my own."

"Raoul, my son, you mustn't forget the white side when you are with the Sultan," she said gently, a touch of chiding in her sad voice.

The boy looked at her speculatively, knowing already that his mother had no affection for the man he called "father."

"You should be proud, not sorry, to be the Sultan's wife," he remarked. "It is an honour for any woman to be loved by the Sultan. Even a woman as lovely and learned as you, little mother."

At twenty-seven Annette was even more beautiful than on the day the Sultan Casim Ammeh first saw her; but more fragile and ethereal. Although her captor's fancy often strayed to other women, he never lost his passion for her.

"Oh, my boy, you don't understand," she said sadly. "When you are a man I'll tell you, and then perhaps you'll think differently."

"When I am a man, I shall be like my father, but richer and more powerful, because I shall have more knowledge, thanks to you, my mother."

"I hope you will be like your father, Raoul, I ask for nothing better."

When her boy reached manhood Annette intended to tell him the truth, and to leave him to deal with the situation as he would.

At ten years, her son had as much general knowledge as the average French boy of his age, thanks to his mother's teachings. And he knew, too, a great deal more than she taught him.

He was a big lad for his years, handsome and quick-tempered, the Sultan's acknowledged heir. On every side there were people anxious to spoil him and curry favour with him. In the scented, sensual atmosphere of the harem, he learnt things his mother would have kept from him. But she was powerless among so many, all ready to flatter her boy and gain his good graces.

"When I grow up," he said to her one day, "I shall have a hundred wives, like my father."

"In the France I come from a man has but one. You must always remember that, Raoul."

"Only one! Then, mother, I call that a poor country. How can a man be satisfied with one woman? My father has promised me wives of my own when I am sixteen."

It seemed to Annette that in this profligate atmosphere her boy was drifting further and further away from her and his own nation; becoming daily more akin to the barbaric people around him.

Every day she felt she must tell him the truth. Yet every day she put it off. For her boy was only a child still, and in his anger and rage he would not be able to keep his knowledge from the Sultan; then evil would befall him.

It was written that many years were to pass before Raoul Le Breton learnt the truth about himself.

Soon after this episode the Sultan took the boy with him on some thieving expedition.

Whilst they were away, one of the deadly epidemics that occasionally visited El-Ammeh swept through the city, claiming among its many victims Annette Le Breton.

CHAPTER IV

With the passing years, the Sultan Casim Ammeh increased in wealth and power. He gave very little thought to France now. It was a vague power, too far away to trouble him, and only once had it really sent a feeler in his direction; that ill-fated expedition headed by Colonel Le Breton.

Emboldened by his success, he had extended his marauding. But, if he heard nothing more of France, France occasionally heard of him, in the form of complaints from various parts of the Protectorate, from other chiefs whose territory he had raided. The Government knew his name but it had no idea where he came from.

On one occasion the Sultan and his robber horde swept down to within a hundred miles of St. Louis. But there he met with a severe defeat. He retired to his desert stronghold, deciding not to adventure in that direction again. And he owed his defeat to strange guns such as had not come into his life before. Guns that fired not a couple of shots, but a whole volley; an endless fusillade that even his wild warriors could not face.

He went back to El-Ammeh determined to get hold of some of those wonderful guns.

Obviously it was out of the question to attack St. Louis where they came from. If they were to be obtained, they must be searched for in some other direction.

Sore with defeat, he brooded on the strange guns. And very often he talked of them to the boy he called his son.

Raoul Le Breton was about thirteen when the Sultan met with his first rebuff at the hands of France. And he had the welfare and prestige of the desert kingdom at heart, and was as anxious as the Sultan to possess this new weapon.

Far away in the south was the outpost of another European power; just a handful of white men struggling to keep a hold on a country an indifferent and short-sighted government was inclined to let slip.

Round and about the River Gambia the British had a footing. Among the men most determined to keep a hold on this strip of territory was Captain George Barclay.

He was a man of about twenty-eight, of medium height and wiry make, with a thin face and steady grey eyes where tragedy lurked. His confrères said that Barclay had no interests outside of his work. But they were wrong.

He had one thing that was more to him than his own life; a tiny, velvety-eyed, golden-haired daughter.

He had come out to North-West Africa in quest of forgetfulness.

At twenty-three, although he was only a penniless lieutenant, the beauty of the London season, the prospective heiress of millions, had thought well to marry him. It was a runaway match. For his sake Pansy Carrington had risked losing both wealth and position. She was only nineteen, and her guardian and godfather, whose acknowledged heiress she was, had disapproved of George Barclay; gossip said because he was madly in love with her himself, although he was nearly thirty years her senior.

However, whether this was so or not, Henry Langham had forgiven the girl. He had taken her back into his good graces, and, in due course, had become godfather to the second Pansy. "Grand-godfather," the child called him as soon as she could talk.

It had seemed to George Barclay that no man's life could be happier than his. Then, without any warning, tragedy came upon him after five years of bliss. For one day his girl-wife was brought back to him dead, the result of an accident in the hunting-field.

With her death all light had gone out of his life. To escape from himself he had gone out to Gambia; and his tiny daughter now lived, as her mother had lived before her, with her godfather, Henry Langham.

But it was not of his daughter Barclay was thinking at that moment; other matters occupied his mind.

He stood on the roof of a little stone fort, gazing at the landscape in a speculative manner.

The building itself consisted of four rooms, set on a platform of rock some three feet from the ground. All the windows were small, and high up and barred. One room had no communication with the others: it was a sort of guardroom entered by a heavy wooden door. To the other three rooms one solid door gave entry, and from one of them a ladder and trap-door led up to the roof which had battlements around it.

Below was a large compound, rudely stockaded, in which half a dozen native huts were built.

In that part of Gambia Captain Barclay represented the British Government. He had to administer justice and keep the peace, and in this task he was aided by a white subaltern, twenty Hausa soldiers, and a couple of maxim guns.

On three sides of the little British outpost an endless expanse of forest showed, with white mist curling like smoke about it. On the fourth was a wide shallow valley, with dwarf cliffs on either side, alive with dog-faced baboons. The valley was patched with swamps and lakes, and through it a river wended an erratic course, its banks heavily fringed with reeds and mimosa trees; a valley from which, with approaching evening, a stream of miasma rose.

Barclay's gaze, however, never strayed in the direction of the shallow valley.

He looked to the north.

A week or so ago word had come through that a notorious raider was on the move; a man whom the French Government had been endeavouring to catch for the last five years or more. What he was doing so far south as Gambia, the district officer did not know. But he knew he was there.

Only the previous day news had come that one of the villages within his, Barclay's, jurisdiction had been practically wiped out. A similar fate might easily fall to the lot of the British outpost, considering that the Arab chief's force outnumbered Barclay's ten to one.

From the roof of his quarters the Englishman saw the sun set. It seemed to sink and drown in a lake of orange that lay like a blazing furnace on the horizon; a lake that spread and scattered when the sun disappeared, drifting off in islands of clouds, gold, rose, mauve and vivid red, sailing slowly across a tense blue sky, getting ever thinner and more ragged, until night came suddenly and swallowed up their tattered remains.

A dense, purple darkness fell upon the land, soft and velvety, that reminded Barclay of his little daughter's eyes. And in a vault as darkly purple, a host of great stars flashed. Away in the forest an owl hooted. From the wide valley came the coughing roar of a leopard. Every now and again some night bird passed, a vague shadow in the darkness. In silver showers the fireflies danced in the thick, hot air. Down in the compound glow-worms showed, looking like a lot of smouldering cigarette ends cast carelessly aside.

Upon the roof, with gaze fixed on the misty, baffling darkness that soughed and hissed around him, Barclay stayed, until the gong took him down to dinner.

There his junior waited, a round-faced youngster of about nineteen.

The meal was a poor repast of tinned soup, hashed tinned beef, yams and coffee, all badly cooked and indifferently served.

During the course of the meal the youngster remarked:

"What a joke if we nabbed the Sultan Casim Ammeh, or whatever he calls himself, and went one better than the French johnnies."

"It would be more than a joke. It would be a jolly good riddance," Barclay responded.

"It's queer nobody knowing where he really comes from."

"You may be sure he doesn't play his tricks anywhere near his own headquarters. More likely than not, he and his cut-throat lot start out disguised as peaceful merchants, in separate bands, and join up when they reach the seat of operations. There are vast tracts of Senegal practically unexplored. They would give endless cover to one of his kidney."

"If you had the luck to bag him, what should you do?"

"Shoot him straight off, knowing the earth was well rid of a villain."

"But what's his idea in coming as far south as this? He's never been heard of on this side of the Senegal River before."

"Plunder. Guns, most likely. He's heard we're none too welcome, and hardly settled here, and thinks we shall prove an easy prey."

However, the little English force was not to prove quite the easy prey the Sultan had imagined when he came south in quest of new weapons.

The next night, without any warning, he attacked Barclay's headquarters.

He struck at an hour when all was darkest; not with his usual swoop of wild horsemen, but stealthily.

Unchallenged and unmolested, he and his following scaled the stockade and crept towards the tiny fort, vague shadows moving silently in the purple darkness.

But each night Barclay had laid a trap for his expected foe.

He knew the enemy force outnumbered his, and that his little handful could be starved out within a week, if the Arab chief wanted to make a siege of it.

Barclay had no intention of letting this come to pass.

He did a bold thing.

Each night, after dark, the little British garrison divided into three units. A Hausa sergeant and fifteen men were left on the roof of the fort. Barclay, two soldiers and one maxim gun, his junior, with two more soldiers and the other gun, crept out from the place, and hid in the dense undergrowth, at different points outside of the stockade; first removing a plank here and there in the enclosure to enable them to work their guns through.

Barclay's ruse succeeded.

Whilst the Sultan and his followers were busy trying to scale the fort and get at the handful of men peppering at them from its roof, without any warning there came an unexpected fusillade from, the rear. He turned and attacked in that direction, only to find a further fusillade pouring in on him from another point.

The Sultan sensed that he had fallen into a trap; that he was surrounded on all sides. Sore and furious he turned to go, more quickly than he had come. But before he had reached the stockade, the world slipped from him suddenly.

CHAPTER V

When the skirmish was over, Barclay and his junior, with half a dozen Hausas and a lantern or two, made a round of the compound, counting the dead and attending to the wounded.

His own garrison was practically unscathed, but his guns had played grim havoc with the attacking party; fully fifty dead and wounded lay within the stockade.

Barclay went about his task cautiously. He knew Arabs and their little ways. Giving no quarter themselves, they expected none, and would sham death and then stab those who came to succour them.

Among the prisoners was a lean, lithe man of about forty, who appeared more stunned than hurt from a bullet that had grazed his forehead. Barclay came across the wounded man just when the latter was coming back to consciousness. Although in dress he differed in no way from the rest of his following, the knives in his belt were heavily jewelled, and gems flashed on his brown fingers.

By the light of a lantern the Englishman scanned him, noting his array of jewels and his cruel, arrogant, commanding face, the face of a savage leader.

"My son," he said to the subaltern, "I believe your joke has come to pass."

"My joke!" the youngster repeated blankly.

Then the light of understanding came to his face.

"You don't mean to say this cruel-looking cuss is the Sultan Casim Ammeh!"

"I'd be surprised to hear he wasn't," Barclay responded.

Suspicious of his man, and knowing him to be no more than stunned, the captain had him handcuffed and locked up in one of the inner rooms of the fort.

When the wounded had been attended to they were left in the guardroom, and the little garrison retired once more within the fort.

The enemy had had such a thorough beating that Barclay did not expect another attack. For all that, he was taking no risks.

Just before daybreak, when the world was a place of curling white mist and greyness, there came a stampede of horses. And, above the thunder of hoofs, the wild Mohammedan war-cry.

"Deen! Deen Muhammed!"

That wild swoop and yell was the Sultan's usual way of attacking.

"It seems we didn't get our man last night," Barclay remarked, as the guns were trained in the direction of the sound. "According to report, this is his usual method of attack."

Out of the greyness of approaching morning a mêlée of wild horsemen appeared. Their leader was hardly the man Barclay had pictured to himself as the blood-stained Arab chief, but a smooth-faced youth in white burnoose, mounted on a huge black stallion.

More than this Barclay did not wait to see. He opened fire on the massed horsemen, his guns playing deadly havoc. Within a few minutes their ranks broke. In wild disorder they turned and stampeded back, soon to be lost in the screening mist.

"I don't think they'll face another dose," the junior remarked.

However, he was wrong.

Presently from out of the fog came the same wild war-cry and the thunder of hoofs. There was another charge with sadly depleted numbers.

For reckless courage Barclay had never seen anything to equal their youthful leader. Again and again he rallied his men and brought them on, until finally, with only about a dozen men, he swept through the deadly zone and on towards the fort.

In the very teeth of the Maxims his black horse literally flew over the high stockade. But the youngster was the only one who faced the guns. His following broke up and turned back under the fierce fusillade.

Although the leader got over the stockade alive, his horse did not. It crashed and fell dead beneath him. With a quick side spring—a marvellous piece of horsemanship—he avoided injury and, with drawn sword, rushed on towards the little fort.

The Hausas would have shot down the reckless youngster, but Barclay stopped them.

"We don't make war on children," he said in their dialect.

A closer inspection showed the leader of the Arab horde to be hardly more than a child; a handsome boy of about fourteen who, suddenly, realising that his followers had deserted him, now stood gazing round in a fierce, thwarted fashion.

On finding he was alone he did not retreat, although Barclay gave him every opportunity. Instead, he stood his ground and hurled a challenge in Arabic at the men clustered on the top of the fort.

Since there was no reply to that, he shouted again, this time in French.

"Who and what is the youngster?" Barclay asked. "He doesn't look any more Arabian than I do. And now he's yelling at us in pure Parisian French."

However, nobody could find any reply. So Barclay descended alone to interview the one remaining member of the Sultan Casim's forces.

He was hardly out in the compound before he wished he had not gone.

He had just time to draw his sword when the boy fell upon him.

Barclay was a skilled duellist, but in this wild youth from the desert he met his match.

For all his finesse and superior height and weight, the Englishman had his cheek laid open and his arm ripped up in the course of a minute. Things would have gone badly with him, except that a shot from his junior put the boy's sword arm out of action.

With a rattle his weapon fell to the ground, his arm useless at his side.

But, even then, there was no plea for mercy. With a proud gesture he threw up his head, facing his enemy in arrogant fashion.

"Kill me," he said in French, "but let my father live."

"Who is your father?" Barclay asked, as with a handkerchief he tried to stop the blood gushing from his cheek.

"The Sultan Casim Ammeh," the boy answered proudly.

The reply told Barclay that the man he had under lock and key really was the marauding Arab chief.

He scanned the boy closely.

Except for his coal-black hair and eyes and fierce, arrogant expression, there was no resemblance between father and son. If he had not heard to the contrary, he would have said the boy was as French as the language he spoke.

"I've no intention of killing you," Barclay remarked. "On the contrary, young man, I'm going to have your arm set and bound up before you bleed to death."

The blood was dripping from the boy's fingers, making a pool on the ground. But he paid no heed to his own hurt. All his thoughts were for the Sultan Casim.

"I'm not asking mercy for myself, but for my father," he said haughtily.

"I'm afraid that's useless, considering two Governments have condemned him."

"You will dare to kill him?"

Barclay said nothing. But his very silence was ominous.

A dazed, incredulous look crossed the boy's face.

As the Englishman watched him it seemed that, blood-stained murderer as the Sultan was, at least this big, handsome son of his loved him.

Like one stunned, the youngster submitted to being led into the fort, where his arm was set and his wounds bound up.

When this was done he said to Barclay:

"I'll give you wealth in jewels that will amount to three hundred thousand francs in French money if you will let my father go free and take my life instead."

Barclay made no reply.

"You will murder my father?" the boy went on, dreading the worst from Barclay's silence.

The word made the Englishman wince. For it did seem like murder with this fierce, handsome boy pleading desperately for his father's life.

Again he said nothing.

To escape from the sight of the pain and anguish his silent verdict had aroused, Barclay went from the room, leaving the youngster in the charge of a couple of soldiers.

About noon that day, at the hands of the British Government, the Sultan Casim Ammeh met a well-deserved end. He met it bravely, (refusing to be blindfolded), with a slight, cruel smile facing the guns levelled at him.

It was evening before Barclay summoned up enough courage to meet his youthful prisoner. And when he did, it seemed he had never seen so much concentrated hatred on any face.

"So, you shot my father?" the boy said in a slow, savage manner.

Barclay had not come to discuss the dead malefactor. He wanted to learn more about the son—where he had learnt his excellent French; how he came to differ so in appearance from the Arab chief and his wild following.

"Your father has paid the penalty of his crimes," he said quietly.

"And you shall pay the penalty of yours!" the boy cried passionately; "for I shall kill you as you have killed my father. Your daughters I shall sell as slaves. Your sons shall toil in chains in my city. Your wives shall become the bondswomen of my servants. Remember, white man, for I do not speak lightly. I will be avenged. I, Casim Ammeh, whose father you have thought well to murder!"

The savage threats of a wild, heart-broken boy did not trouble George Barclay much. But his mind did go to his tiny four-year-old daughter, and he was glad she was safe in England and not within reach of this savage lad.

At that moment he was more worried about his youthful captive than the latter's wild threats.

He did not want to make a criminal of the boy; for, obviously, whatever wrong he had done was done under the influence of his savage father. And there looked to be the makings of a fine man in him, if only he had good guidance.

Barclay decided to put the case before the French Government, together with a suggestion of his own—that the youngster should be sent somewhere where he could be brought up to be of use to the country, not a constant thorn in its flesh, as his father had been.

But Captain Barclay need not have troubled himself with making plans for the future of the youthful Sultan of El-Ammeh, for that night the boy escaped, and his future was left in his own hands.

CHAPTER VI

After some two years out in Gambia, George Barclay returned to England. He returned with a scar across his right cheek.

That scar was the first thing his little daughter remarked upon when the excitement of reunion had died down.

Perched on his knee, she touched it with gentle little fingers and kissed it with soft lips.

"Who has hurt my nice new Daddy?" she asked distressfully.

Then there followed the story of the youthful Sultan Casim Ammeh.

"Oh, what a wicked boy!" she exclaimed.

Then she glanced across at her godfather who was sitting near.

"Isn't he a bad, naughty boy, Grand-godfather, to want to kill my Daddy and sell me as a slave?"

Henry Langham had listened to the story with interest, and very heartily he agreed with her.

"I shall tell Bobby," the little girl went on indignantly, "and he'll go and kill the Sultan Casim Ammeh."

"Who's Bobby?" her father asked.

"My sweetheart. Master Robert Cameron."

"So in my absence I've been cut out, have I?" her father said teasingly. "I'm dreadfully jealous."

But Pansy snuggled closer to him, and her arms went round his neck in a tight hug.

"There'll never be anyone as nice as my Daddy," she whispered.

George Barclay held the tiny girl closer, kissing the golden head.

Often during his months in England, Pansy would scramble on his knee and say:

"Daddy, tell me the story of Casim Ammeh. That naughty boy who hurt your poor face."

To Pansy it was some new Arabian Nights, vastly interesting because her father was one of the principal characters. Although she had heard it quite fifty times, she was ready to hear it quite fifty times more.

"But, my darling, you've heard it scores of times," Barclay said one day.

For all that he told the story again.

Quietly she listened until the end was reached. Then she said:

"I don't like him. Not one little bit. Do you like him, Daddy?"

"To tell you the truth, Pansy, I did like him. He was a very brave boy."

"I shall never like him, because he hurt you," she said firmly, her little flower-like face set and determined.

"Well, my girlie, you're never likely to meet him, so it won't make much difference to him whether you like him or not."

But—in the Book of Fate it was written otherwise.

CHAPTER VII

Somewhere off the Boulevard St. Michel there is a cabaret. The big dancing hall has red walls painted with yellow shooting stars, and, overhead, electric lights blaze under red and yellow shades. There is a bar at one end, and several little tables for the patrons' use when they tire of dancing. In the evenings a band, in seedy, red uniforms with brass buttons, fills, with a crash of sound, an atmosphere ladened with patchouli and cigarette smoke, and waiters, in still more seedy dress-suits, attend to the tables. Never at any time is the gathering select, and generally there are quite a few foreigners of all colours present.

One night, the most noticeable among the patrons was an Englishman, well-groomed and tailored, and a big youth of about eighteen in a flowing white burnoose.

They were in no way connected with each other, but chance, in the shape of their female companions, had brought them to adjacent tables.

The girl with the youngster was very pretty in a hard, metallic way, with the white face and vivid red lips of the Parisienne, and brown eyes, bright and polished-looking, that were about as expressionless as pebbles. She was attired in a cheap, black evening dress, cut very low, and about her plump throat was a coral necklace. Her hair was elaborately dressed, and her shoes, although well worn, were tidy.

By day, Marie Hamon earned a meagre living for herself in a florist's shop. At night, she added to her earnings in the recognized way of quite a few of the working girls of Paris. And this particular cabaret was one of her hunting grounds.

As Marie sat there "making eyes" at the youth in the white burnoose, the man at the next table remarked in French, in an audible and disgusted tone:

"Look at that girl there making up to that young nigger. A beastly spectacle, I call it."

Before his companion had time to reply the youth was up, his black eyes flashing, and he grasped the Englishman's shoulder in an angry, indignant fashion.

"I am no nigger!" he cried. "I'm the Sultan Casim Ammeh."

"I don't care a damn who you are so long as you keep your black paws off me!"

The youth's hands were not black, but deeply bronzed like his face, which looked darker than it really was against the whiteness of his hood.

"Take back that word," he said savagely, "or, by Allah, it shall be wiped out in blood!"

He drew his knife. The girls screamed. Excited waiters rushed towards the table. The mixed company stopped dancing and pressed forward to watch what looked like the beginning of a royal row. Such incidents were by no means unusual in the cabaret.

Only the Englishman remained calm. He grasped his opponent's wrist quickly.

"No, you don't," he said. "You damned niggers seem to think you own the world nowadays."

There was a brief scuffle. But the Englishman was big and heavy, and half a dozen waiters were hanging on to the enraged and insulted youth. His knife was wrested from his hand. He was hustled this way and that; and, finally, worsted and smouldering, he retired, to be led to another and more distant table by his female companion.

The episode was over in a couple of minutes. Disappointed at the lack of bloodshed, the spectators returned to their dancing. Relieved, the waiters went back to their various spheres. The Englishman seated himself again as if nothing had happened. At a distant table the youth sat and glowered at him.

"Who is that man?" he asked presently, pointing a lean forefinger at his late opponent.

Marie shrugged her plump shoulders.

"I've never seen him here before. He looks to me like an Englishman."

With renewed interest the youth studied the distant figure, hate smouldering in his black eyes.

So he was one of the nation who had murdered his father! This man who had insulted him.

But, for all his hatred of the Englishman, reluctantly he admired his coolness and his clothes.

The world had enlarged for Annette Le Breton's son since his first experience with the English.

On escaping from Barclay, with the remaining handful of the defunct Sultan's following, he had returned to El-Ammeh, at the age of fourteen its recognised ruler.

The boy was not lacking in sense. Defeat at the hands of both British and French made him decide to give up what had been the late Sultan's chief source of income—marauding. With a wisdom beyond his years, Casim Ammeh, as he was now always called, decided to go in for trading; and before many years had passed he saw it was a better paying game than marauding, despite its lack of excitement.

Then he extended his operations.

There were always caravans coming to his desert city, and a great demand for articles that came from the Europe his mother had told him of.

With one or two of his principal merchants he went down to St. Louis, but he did not go as the Sultan Casim Ammeh; that name was too well known to the French Government. Instead, he went under the name his mother used to call him, Raoul Le Breton. And under that name he opened a store in St. Louis.

There was a new generation in the town since his real father's day, and the name roused no comment. It was an ordinary French one. In St. Louis there were quite a few half-breed French-Arabs, as the youth supposed himself to be, living and trading under European names.

His business ventures were so successful that he opened several more stores at various points between St. Louis and his own capital; but the whereabouts of his own city he did not divulge to strangers.

At sixteen it had seemed to the boy that St. Louis was the hub of the universe; but at eighteen a craving that amounted to nostalgia drove him further afield—to Paris.

And he went in Arabian garments, for he was intensely proud of his sultanship and the desert kingdom he ruled with undisputed sway.

To his surprise, he felt wonderfully at home in his mother's city. It did not feel as strange as St. Louis had felt, but more as if he had once lived there and had forgotten about it.

He had been a couple of days in Paris, wandering at will, when on the second evening his wanderings had brought him in contact with Marie Hamon. She was by no means the first of her sort to accost him, but she was the first he had condescended to take any notice of. She had smiled at him as, aloof and haughty, he had stalked along the Boulevard St. Michel, and had fallen into step beside him. He had looked at her in a peculiar manner that was half amusement, half contempt, but he had not shaken her off.

She had suggested they should have dinner together, and he had fallen in with her suggestion; not exactly with alacrity, but as if he wanted to study the girl further. For all her plump prettiness and profession, there was a shrewd, sensible air about her. Afterwards, at her instigation, they had repaired to the cabaret.

As the youth continued to scowl at the distant Englishman, with the idea of preventing further trouble, Marie tried to get his mind on other matters.

"Casim, let's have a dance?" she suggested.

"I can afford to pay for hired dancers, so why should I posture for the benefit of others?" he asked scornfully.

She tittered.

"Well, get me another drink instead, then."

He beckoned a waiter and gave a curt order. However, he did not touch the cheap champagne himself. Instead, he kept strictly to coffee.

"Have a drop of cognac in it to cheer you up a bit," Marie said. "You make me feel as if I were at a funeral."

"I'm a Mohammedan, and strong drink is forbidden."

"You are the limit! I shouldn't quarrel with the good things of this life even if I were a Mohammedan."

"By my religion women have no souls," he replied in a voice that spoke volumes.

But Marie was not easily abashed.

"The lack of a soul doesn't trouble me in the least," she responded lightly. "A pretty body is of greater use to a woman any day. Do you think I'm pretty, Casim?" she finished coquettishly.

"I shouldn't be with you unless you were," he replied, as if her question were an insult to his taste.

For some minutes there was silence. As the girl sipped her champagne she watched her escort in a calculating manner.

"You've got lots of money, haven't you?" she said presently.

"Not as much as I intend to have," he replied.

"But enough to buy me a new frock?" she questioned.

"Fifty, if you want them."

Marie threw her arms around his neck.

"You nice boy!" she cried, kissing him soundly.

He resented her attentions, removing her arms in a none too gentle manner.

"I object to such displays of affection in public," he said, with an air of ruffled dignity.

"Come home with me, then," she suggested.

"Home" to Marie was an attic in a poor street. There Casim Ammeh went, not as a victim to her charms, as she imagined, but seeing in her a means to his own end.

The next morning as he sat at breakfast with the girl—a meagre repast of black coffee and rolls—from somewhere out of his voluminous robes he produced a string of pearls and dangled it before his hostess. Marie looked at them, her mouth round with surprise, for they were real and worth at least ten thousand francs.

"If I give you these, Marie, will you teach me to become a Frenchman?" he asked.

"Won't I just!" she cried enthusiastically, and without hesitation continued: "First of all we must get an apartment. And, mon Dieu! yes, you must cut your hair short."

The youth wore his hair long, knotted under his hood in the Arab fashion.

It was three months before Casim Ammeh left Paris. And he left it in a correctly cut English suit and with his smooth, black hair brushed back over his head. In the spick-and-span young man it would have been difficult to recognise the barbaric youth who had come there knowing nothing of civilised life except what his mother had told him and what he had seen in St. Louis; and, what was more, he felt at ease in his new garments, in spite of having worn burnoose and hood all his life.

The day before he left, Marie sat with him in the salon of the pretty flat they had occupied since the day they struck their bargain. And she looked very different, too.

Her evening frock was no longer of shabby black. It was one of the several elaborate gowns she now possessed, thanks to the young man. And she no longer wore a string of coral beads about her pretty throat, but the pearl necklace.

Although Marie had taken on the youth as a business speculation, within a few days she loved him passionately. She was loath to let her benefactor go, but all her wiles failed to keep him.

"When you're back in Africa you won't quite forget your little Marie who taught you to be a man, will you?" she whispered tearfully.

Her remarks made him laugh.

"I've had women of my own for at least a year before I met you," he replied.

It seemed to Marie she had never really known the youth who had come to her a savage and was leaving her looking a finished man of the world. He never talked to her of himself or his affairs. Although kind and generous, he demanded swift obedience, and he treated her always as something infinitely inferior to himself.

"Say you love me," she pleaded. "That you'll think of me sometimes."

"Love!" he said contemptuously. "I don't love women. I have them for my pleasure. I'm not one of your white men who spend their days whining at some one woman's feet pleading for favours. Women to me are only toys. Good to look upon, if beautiful, but not so good as horses."

"Oh, you are cruel!" she said, weeping. "And I thought you loved me."

"It is the woman's place to love. There are other things in a man's life."

Marie realised she had never had any hold on her protégé. She had been of use to him, and he had paid her well for it, and there, as far as he was concerned, the matter ended.

Being sensible, she sat up and dried her tears, gathering consolation from the fact that he had been a good speculation. There would be no immediate need to return to the florist's shop when he had gone. In fact, if she liked to sell the necklace, she could buy a business of her own.

"Shall you come to Paris again, Casim?" she asked.

"Oh yes, often. It's a good city, full of beautiful women who are easy to buy."

But he made a reservation to himself.

When he came again he would come under the name his mother used to call him—Raoul Le Breton, and he would come in European clothes. Then the English he hated would not be able to hurl that detestable word "nigger" at him.

CHAPTER VIII

In a select French boarding-school a girl sat reading a letter. She was about fifteen years old, a slender, lovely child, light and graceful, with a cascade of golden curls reaching to her waist, and wide, purple eyes. Her complexion was perfect. She had a vivid little red mouth, impulsive and generous, and a pink rose on each cheek.

On reading the letter, sorrow clouded her face. For it ran:—

"My Dear Little Pansy,

When you get this letter I shall be with your mother. I am leaving you the money she would not have. And it was worth having, you will agree, for it will bring you in about £60,000 a year. The only condition I make is that you take the name your mother refused, your own second name. And my one hope is that you will be more successful in love than I was.

Your affectionate 'grand-godfather,'

Henry Langham."

For some minutes Pansy sat brooding on her godfather's end. The poor old boy had been awfully ill for a long time, and now he was dead.

She blinked back a couple of tears. Then her thoughts went to the fortune she had inherited.

Presently she crossed to the mirror and looked at herself.

"No, old girl," she said to her reflection, "your head isn't turned."

Then she slipped the letter into her pocket and made straight for her great friend and confidante.

To the average eye there was nothing about Miss Grainger to attract a vivid, beautiful girl like Pansy Barclay—Pansy Langham as she would be now. Miss Grainger was middle-aged, grey-haired, thin and depressed-looking: the down-trodden English mistress, with no qualifications except good breeding.

She was poor and friendless, and life had gone hard with her, but these facts were sufficient to fill Pansy's heart with a warmth of generous affection and sympathy.

The girl's principal thought as she went along was not so much of the millions she had just inherited, but that she had always wanted to do something for Miss Grainger, and now she saw a way of doing it.

She entered the room that served the English mistress as bedroom, study and sitting-room, disturbing the latter in the midst of correcting an accumulated pile of exercise books.

"What is it, Pansy?" she asked, smiling at her favourite.

"Miss Grainger, you'll be pleased to hear I'm a millionaire."

The English mistress put down her pen carefully, and then sat staring at the child.

"Really, my dear," she said in a bewildered tone, "you have a way of saying the most surprising things in the most matter-of-fact manner. But, since you're saying it, it must be true."

"That's a character in itself," Pansy remarked, smiling, a smile that brought to view several bewitching dimples.

She produced the letter and handed it to her friend.

The English mistress read it through.

"Sixty thousand pounds a year!" she exclaimed. "It makes my head reel."

"Then yours can't be so firmly screwed on as mine. Mine isn't turned one little bit. I looked at myself in a glass to see."

"But what are you going to do with it all?" the governess asked helplessly.

"Spend it, of course. I take after my father and never shirk an unpleasant duty," she went on, a mischievous glint in her eyes. "To begin with, you, Miss Grainger, are going to be my companion, and we'll have a yacht and go all round the world together, and see and do everything that can be seen and done."

"You'll get married, Pansy," the governess said, looking lovingly at the beautiful flower-like, little face.

"Not much! You dear old antiquated thing. I'm not going to be tied by the leg in that fashion."

"As the English mistress, I must remind you that 'tied by the leg' is slang."

"When you're my companion you'll be talking slang yourself. I'm not so sure I won't make that one of the stipulations," the child went on teasingly. "It'll be such a change for you after thirty years of correcting stupid exercises."

"It will be rather," Miss Grainger said wistfully.

"And I shall come out at seventeen," Pansy went on. "I must start as early as possible if I'm to spend all that money. I shall write and ask my father if I may come out at seventeen. Do you think he'll refuse?"

"No man will ever refuse you anything, Pansy. You're too sweet and good and beautiful."

"And rich. Don't forget the rich. That'll be a tremendous draw."

Miss Grainger smiled at her favourite.

"I hope the man who marries you will pick you for your good heart and generous nature, not your looks and money," she remarked.

"Still harping on that old string, Mrs. Noah. Women don't get married nowadays if they can afford to stay single."

Then the school dinner-bell ringing sent Pansy from the room, but not before she had given an impetuous hug and kiss to her friend.

CHAPTER IX

Paris always has a welcome for millionaires. And it always had a specially warm welcome for Raoul Le Breton, the African merchant-prince. Not only was he fabulously rich, but he was young and remarkably good-looking. It was whispered that he had Arab blood in his veins, but he was wealthy enough for the majority to overlook this drawback.

Like many modern Frenchmen, he dabbled in "le sport." He was a brilliant tennis player, a worthy opponent at billiards, and he kept a stud of race-horses. There was hardly an actress of any repute and with any pretence to youth and beauty who had not had his patronage at one time or the other. Match-making mothers with marriageable daughters laid snares about his feet. With surprising agility he avoided their traps. None of the daughters proved sufficiently tempting to turn him from the broad, smooth way of gay Parisian bachelorhood to the steep and jagged path of matrimony.

Raoul Le Breton was about twenty-five when he paid his sixth visit to Paris. He came now for about three months every year. And he always came in style, with a whole retinue of Arab servants—silent, discreet men who never gossiped about their master. It was whispered also that out in Africa he had a whole harem of his own; moreover, that he was some big chief or the other. In fact, many things were whispered about him, for, on the whole, Paris knew very little except that he was wealthy and wild.

His French acquaintances tried to learn more of his doings through the medium of his own private doctor, a stout Frenchman who accompanied the young millionaire to and fro. But Dr. Edouard refused to gossip about his friend and patron.

In spite of his success, the young Sultan of El-Ammeh had not forgotten George Barclay.

On getting more in touch with civilisation and its ways he had tried to find out the name of the man who was responsible for the death of his supposed father. It was not an easy task. George Barclay had left Gambia five years before Raoul Le Breton set about his investigations. There had been a succession of men since Barclay's time, and the shooting of a native malefactor was not a matter of great note in the annals of a Government.

However, eventually Le Breton managed to establish the identity of the man he looked upon as his father's murderer.

But to trace George Barclay in England proved an even more difficult task than tracing him in Africa.

The Englishman had not stopped long in his country. In search of forgetfulness, he had gone from one place to another, holding posts in various parts of the Empire.

The Sultan Casim Ammeh was twenty-five when he heard that Barclay was in the Malay Straits.

The news came to him in Paris just when he was setting out for an evening's amusement in company with Dr. Edouard. The letter was brought to him as he stood in dress-suit, opera hat in hand, in his own private sitting-room at the palatial hotel he always patronised when in Paris.

On perusing it he turned to his companion, and said, with an air of savage triumph:

"Well, Edouard, I've managed to trace my man at last."

The doctor knew who the man in question was, for he, Edouard, was the Sultan Casim's one confidant. Rather uneasily he glanced at his patron. He wished the young man would be content with money and the many joys and pleasures it could buy—for Casim Ammeh was no longer a strict Mohammedan—and would not be always hankering after vengeance, a vengeance that might embroil him with England and bring his wild and brilliant career to an abrupt close.

"Where is George Barclay?" Edouard asked uneasily.

"In the Straits Settlements."

The doctor experienced a feeling of intense pleasure on hearing Barclay was in so remote a spot.

"It'll be difficult for you to get hold of him there," he remarked, trying to keep out of his voice the relief he was feeling.

"He won't stay there for ever. I've waited eleven years for my vengeance. I can go on waiting a little longer, until Fate thinks well to place him in a more accessible position."

With a savage expression Le Breton turned to a desk. Sitting down, he wrote to his agents telling them to keep him informed of George Barclay's movements.

PART II

CHAPTER I

The harem in the palace of El-Ammeh led into a large hall with carved doors and tiny arabesque windows, fretted and scrolled, with no one spot big enough to squeeze more than a hand through.

Generally speaking, the women of the harem preferred the large hall, where they could gossip among themselves and with their attendant women, to the little rooms that were their own private quarters.

But there was one special apartment that they all in turn had striven after and, in turn, had failed to attain. No one in the harem had seen the room except old Sara, and she had plenty of tales to tell about its magnificence. It was a big gilded chamber, with a ceiling like the sky on a desert night, and great golden, jewelled lamps. There was a wonderful bathroom, a fretted gallery that gave a wide view of the desert, a walled garden full of roses, and, above all, a door that led into the Sultan's private suite. The room had had no occupant since the days of the Sultan's mother, the Lady Annette, the first wife and favourite of his father. And Sara had been her special slave and attendant.

It could be reached from the harem. At one point behind the silken curtains a narrow stairway led upwards, and ended in a scented, sandalwood door. But the door was always locked, and only the Sultan had the key. It was common harem gossip that in that room he would place the one among his slaves whom he deigned to make his first wife.

Although the law allowed him four, and as many slaves as he fancied, so far he had no legal wife. It was strange, considering he was nearly thirty. But, in many ways, he differed from all the previous Sultans. According to old Sara, it was because his mother belonged to quite another race, and had come from a land as remote from El-Ammeh as Paradise, where the women were all white, a land that the Sultan now visited yearly.

For that land he was starting to-morrow.

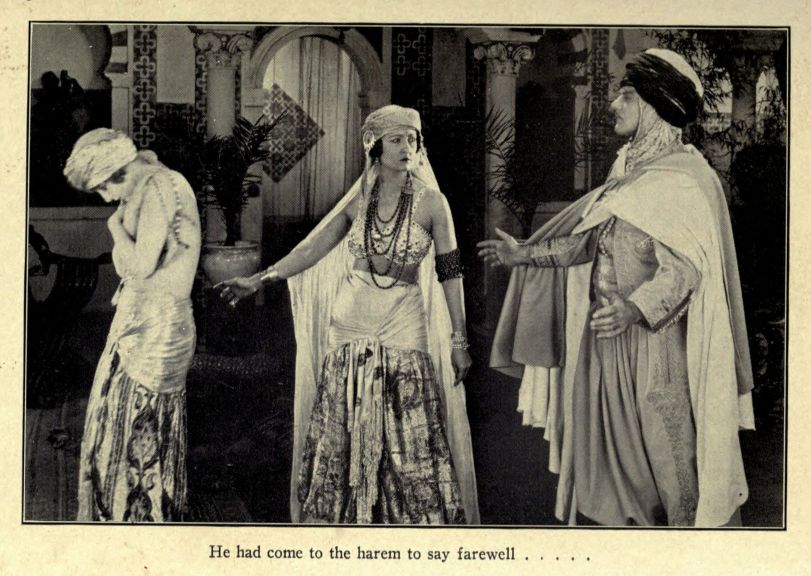

He had just been to the harem to say farewell to the half-dozen girls there, departing with promises of new jewels and novelties to please and amuse these toys of his on his return. And now he lingered with his newest slave and favourite, Rayma, the Arab girl he had bought but six weeks ago.

He had come to the harem to say farewell.....

Envious glances were cast towards the door behind which the Sultan Casim Ammeh and his new slave, Rayma, took farewell of one another.

One girl more than the others watched the door with hurt, angry, jealous eyes.

She was about twenty-three, with a full figure, a creamy skin, a profusion of long black curls, and great soft, languid eyes—a half-breed Spanish-Moorish girl of the true odalesque type.

Her attire was scanty. A red silk slip draped her from shoulder to knee, held on by ribbon straps; and on her hands and wrists and neck a quantity of barbaric jewelery flashed.

"I pray to Allah that on his travels our Sultan will find some woman he loves better than Rayma," she said, spite and jealousy in her soft voice.

"No, I don't pray that, Leonora," one of her companions remarked. "For you took him from me, and what am I now? Like you, a scent that has lost its savour; for it is but a shred of love that the Lord Casim has now for me. No; I pray may he know what it is to love and be denied, for too easily do women's hearts go to him. And no man values what comes to him cheaply. Our day is done, mine and yours, Leonora, as Rayma's will be when another woman takes his fancy. No, pray as I do, that he may love a woman who has no desire for him, who spurns his love—a woman whose people will not sell her, who is no slave put up for auction, as we were. May his heart ache, as mine has ached. May passion keep him sleepless, with empty arms and craving desire. May love prove to him a mirage that he can see yet never grasp!"

Unconscious of these wishes, the Sultan Casim Ammeh and the slave girl Rayma lingered together behind closed doors.

The moon shone into the little apartment, showing a big man in a white burnoose, and at his side a girl lay, looking at him with tearful, love-laden eyes.

She was about seventeen, with an amber skin and a cloud of straight black hair that reached to her heels. A cloud out from which looked a little oval face, with great black eyes and a small red mouth, a perfect type of Arab beauty.

"My Lord Casim, beloved, my heart breaks at the thought of your going," she said tearfully.

Smilingly he watched her, caressing her in an indulgent fashion.

"But, my desert flower, I shall come back again."

"But it is so far. And in that Paris there are so many women. I know, because Sara has told me. And all their arms will be stretched out to keep you there."

"No arms have kept me there for longer than three months," he replied.

"And mine! Mine are not strong enough to keep you here?" she sobbed.

He drew the sobbing little beauty into his embrace, and kissed her tear-stained face.

"Tell me, my jewel, what favour can I grant you before I go?"

"I want nothing but just to rest upon your heart for ever."

With a tender hand he stroked her long black hair, and tried to soothe away the tears; flattering tears, resulting from his coming departure.

"Don't go to Paris, Casim, beloved," she whispered. "Stay in El-Ammeh. Paris is so far, and I am so ignorant of all outside of the desert. Ignorant of everything except love and you. Think, my lord, only six weeks have we been together, and now you would go! Only six weeks since my father brought me from the desert to sell me to the Sultan Casim Ammeh. How afraid I was until I saw you. And then I was afraid I might not find favour in your sight. For my heart was yours the moment our eyes met. Only six weeks ago! Casim, don't go," she implored. "Stay with me, for my heart is breaking."

"Little one, there is business as well as love," he said gently.

"I think of nothing but love."

"Love is quite enough for any girl to think of."

"And those women in Paris, do they think only of love?"

"No; they think of money as well. That's why I prefer you."

She slipped her slim arms about his neck, pressing, her slight form against him, kissing him passionately.

"Let me live in the gilded chamber until you come back," she whispered, "and then I should feel the most honoured among your slaves."

However, he avoided this suggestion.

"We'll see about that when I return," he answered with an amused, indulgent air.

Then he held the girl closer.

"Now, before I go, Rayma, is there nothing you want? Nothing I can do for you?"

"There is one thing, my Sultan. Sell Leonora. I hate her. She's a great fat toad, always plotting and planning to steal your heart from me."

"I couldn't do that. I'm not quite like your desert men, remember. I can't sell a woman who has once pleased me. But, on my return, I'll find her a nice husband, if that will satisfy you."

There was a note in his voice that brooked no argument; and the girl, reared for the harem, was quick to notice it.

She gave a sharp glance at her owner. It seemed that a man she did not know stood behind her Sultan, indulgent master as he had proved. A man she had no hold over.

CHAPTER II

In one of the hotels in the Island of Grand Canary dinner had just been served. Around the door of the large dining-hall the manager, the head waiter and several underlings hovered, with an air of awaiting the arrival of some important personage.

Presently two people appeared in the doorway.

One was a middle-aged woman with grey hair and a prim expression. She was wearing a plain black silk evening dress, and she had the look of a retired governess. Her companion was of quite another type. She was a slender, graceful girl of medium height, with a mop of short, golden curls dancing round a small, frank face, that gave her the look of some lovely, delicate schoolboy. She wore a simple white silk frock, and her only mark of wealth was a large diamond hanging from a thin platinum chain about her slender neck; a gem in itself worth a fortune.

Evidently she was the personage expected. As she appeared the manager went forward to meet her. She smiled at him in a friendly, affable manner. With him at her side, she and her companion went up the big room, towards a specially reserved table, the head-waiter and a little group of others following behind.

As she came up the room, a man seated at one of the tables in the center of the room said to his neighbour:

"Who is that girl? The whole hotel is falling over itself to wait on her."

The speaker was a short, thick-set man, with a red face and fishy eyes.

"That's Pansy Langham, the millionairess," his neighbour replied. "She came over in her yacht from Teneriffe this afternoon. Barclay her name was before she came into her money."

"A millionaire, is she? That's the second one of the species in Grand Canary then. For there's a French millionaire staying in a villa at the back here. Le Breton, his name is. But what's brought the girl to these parts? There's not much here to attract a woman with money."

"She's here for her health, I believe."

"Not lungs, surely! She looks healthy enough."

"No, she had an accident about a couple of months ago. Some half-mad horse mauled her horribly, all but killed her. I remember reading about the case in the papers. They say she's a very decent sort, in spite of her millions. Gives an awful lot away in charity."

As the girl approached the table, the red-faced man screwed an eyeglass into one fishy eye and surveyed her from head to foot.

"She's not bad looking," he said in a condescending manner, as if it were his prerogative to criticise every woman who crossed his horizon. "But she's not a patch on the red-haired woman in the villa at the back here. Now, she's what I call a beauty."

He did not trouble to lower his voice, and his words reached Pansy.

She glanced in his direction and wrinkled her pretty nose, as if she were smelling a bad smell. And with no more notice than that, she passed on to her own table.

CHAPTER III

Just off the main road between the Port and the city of Las Palmas, Grand Canary, a villa stood. It was situated on a hill; a white, flat-roofed building, set in a pleasant garden. Long windows opened on a lawn surrounded by trees.

Out from one of the windows a flood of light streamed and mingled with the silver of the night. The apartment it came from was elaborately furnished, in an ornate French style, with gilded furniture, bevelled mirrors, and satin-covered chairs and lounges.

On one of the latter a woman lolled back amongst an array of soft cushions. She was big and voluptuous-looking, with a dead-white skin, a mass of flaming red hair, and eyes green as the emerald necklace she wore.

She had on an extremely low-cut, black satin dress, that suited her style and colouring. And she made a striking, if somewhat bizarre, picture.

But attractive and unique as she looked, the man sitting with her appeared more interested in the view from the window than in his companion.

From there, a glint of moonlit sea showed between the vaguely moving trees; a peaceful stretch that spread away to the purple, misty horizon.

He was a big man of about thirty, well groomed and handsome, with smooth black hair, close-clipped moustache, and dark, smouldering eyes that had a latent searching look at the back of them. He was in evening attire, with black pearl studs in his pleated dress shirt.

For some time the two had been sitting in silence; the man's gaze on the sea; the woman's on the man, in a hungry, anxious manner.

"You've got one of your restless moods on to-night, Raoul," she said presently.

"I get them frequently nowadays. Nothing ever satisfies me for long."

She smiled at him, a soft, slow smile.

"Yet I have satisfied you longer than most, for you are still here with me."

"It's not you so much, Lucille, as business that keeps me here."

"I believe you have no heart at all," she cried, a catch of pain in her voice. "You look upon all women as animals."

"You are a most handsome animal, you must agree," he replied.

"You talk as if you'd bought me."

"I don't know that I ever put it quite so crudely as that."

"Put it as crudely as you like," she cried in a sudden gust of temper. "You have taken all from me and given me nothing in return."

He made no reply. In a slightly amused manner his glance rested on her emerald necklace.

"You may look," she went on passionately. "But I want more than gifts. I want love, not just to be the creature of your passions."

"Then you want too much. There's no such thing as love between men and women. There's only passion."

"You are cruel," she moaned.

"Cruel! Merely because I refuse to be enslaved by any one woman, eaten up in mind and body and soul, as some of the men I know are? I wasn't brought up to look upon women as superior beings, and I've never met one yet to make me want to change my sentiments. They are here for my convenience and pleasure, and nothing more."

There was silence again.

Lucille sighed.

She knew she had no hold over him other than her sex, and never had had. Heroics, temper and entreaties had no effect on him whatsoever; he remained always unmoved and indifferent.

With a shrug she picked out a chocolate from a large box at her side. Then she changed the conversation.

"What's the business, Raoul? I'd no idea you had any here. I thought ours was a pleasure trip, purely—or impurely."

"The business is strictly private," he replied, a savage note in his voice.

A month before, on leaving Paris, when Le Breton had asked Lucille Lemesurier, the actress, to accompany him on his yacht and spend a week or so in Grand Canary, it had been for pleasure solely.

But a few days ago a letter had reached him.