![[ภาพประกอบแสดงนางฟ้ากำลังดูแลสวน]](https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/67175/images/i28.jpg)

LEGEND LAND

Being a collection of some of the

OLD TALES told in those Western

Parts of Britain served by the

GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY, now

retold by LYONESSE

VOLUME ONE

Published in 1922 by

THE GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY

[FELIX J. C. POLE, GENERAL MANAGER]

PADDINGTON STATION, LONDON

CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

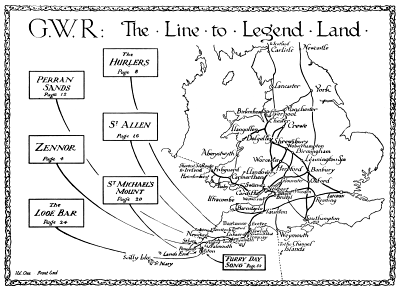

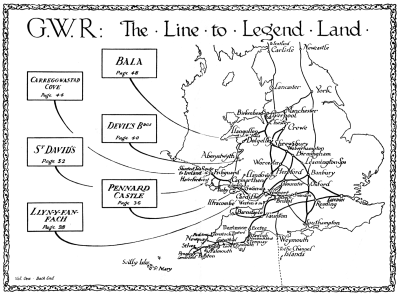

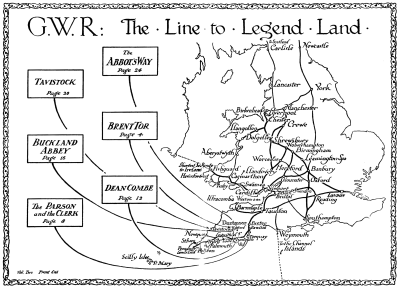

This is a reprint in book form of the first series of The Line to Legend Land leaflets, together with a Supplement, "The Furry Day Song."

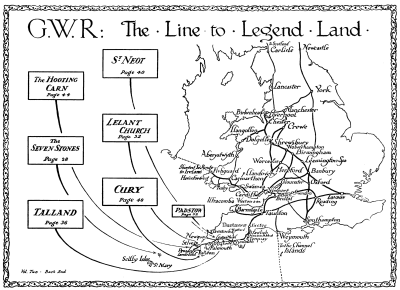

The Map at the beginning provides a guide to the localities of the six Cornish legends and the "Furry Day Song"; that at the back to the six stories of Wales.

Printed by Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Company Limited,

One New Street Square, London, E.C.4

FOREWORD

In those older, simpler days, when reading was a rare accomplishment, our many times great-grandparents would gather round the blazing fire of kitchen or hall on the long, dark winter nights and pass away the hours before bedtime in conversation and story-telling.

The old stories were told again and again. The children learned them in their earliest years and passed them on to their children and grandchildren in turn. And, as is natural, in all this telling the stories changed little by little. New and more familiar characters were introduced, or a story-teller with more vivid imagination than his fellows would add a bit here and there to make a better tale of it.

But in origin most of these old legends date from the very dawn of our history. In a primitive form they were probably told round the camp-fires of that British army that went out to face invading Cæsar.

Then with the spread of education they began to die. When many folk could read and books grew cheap there was no longer the need to call upon memory for the old-fashioned romances.

Yet there have always been those who loved the old tales best, and they wrote them down before it was too late, so that they might be preserved for ever. A few of them are retold briefly here.

All people should like the old stories; all nice people do. To them I commend these tales of Legend Land, in the hope that they may grow to love them and the countries about which they are written.

LYONESSE

THE MERMAID OF ZENNOR

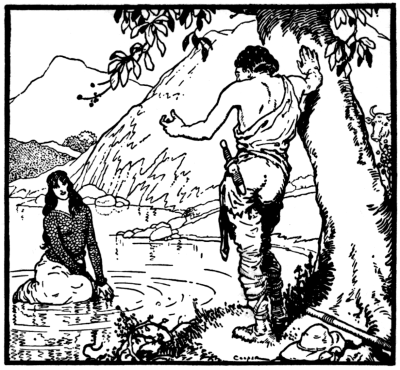

Carved on one of the pews in the church of Zennor in West Cornwall is a strange figure of a mermaid. Depicted with flowing hair, a mirror in one hand and a comb in the other, the Zennor folk tell a strange story about her.

Years and years ago, they say, a beautiful and richly dressed lady used to attend the church sometimes. Nobody knew where she came from, although her unusual beauty and her glorious voice caused her to be the subject of discussion throughout the parish.

So attractive was she that half the young men of the village fell in love with her, and one of them, Mathey Trewella, a handsome youth and one of the best singers in the neighbourhood, determined that he would discover who she was.

The beautiful stranger had smiled at him in church one Sunday, and after service he followed her as she walked away towards the cliffs.

Mathey Trewella never returned to Zennor, nor did the lovely stranger ever attend church again.

Years passed by, and Mathey's strange disappearance was almost forgotten when, one Sunday morning, a ship cast anchor off Pendower Cove, near Zennor. The captain of the vessel was sitting idling on the deck when he heard a beautiful voice hailing him from the sea. Looking over the side he saw the mermaid, her long yellow hair floating all around her.

She asked him to be so kind as to pull up his anchor, for it was resting upon the doorway of her house [6]under the sea and she was anxious to get back to Mathey, her husband, and her children.

In alarm, the captain weighed anchor and stood out to sea, for sailors fear that mermaids will bring bad luck. But later he returned and told the Zennor folk of Mathey's fate, and they, to commemorate the strange event, and to warn other young men against the wiles of the merrymaids, had the mermaid figure carved in the church.

And there it is to-day for all the world to see, and to prove, to those who do not believe the old stories, the truth of poor Mathey Trewella's sad fate.

Zennor is a lovely moorland village in the neighbourhood of some of the wildest scenery in Cornwall. To the south-west rugged moors stretch away to the Land's End. To the north a quarter of an hour's walk brings you to the coast with its sheltered coves and its cruel cliffs. Gurnard's Head, one of the most famous of all Cornish promontories, is less than two miles away. Grim, remote, yet indescribably fascinating, the country around Zennor is typical of that far western corner of England which is swept continually by the great health-giving winds of the Atlantic.

In its sheltered valleys flowers bloom all the year round. On its bold hill-tops, boulder-strewn and wild, there remain still the old mysterious stones and the queer beehive huts erected by men who inhabited this land in the dark days before Christianity.

Gorse and heather riot over the moorland. There [7]is a charm and peace about this too little known country that compels health and well-being.

Yet Zennor is only five and a half miles by the moorland road from St. Ives, that picturesque little fishing town that artists and golfers know so well. St. Ives, less than seven hours' journey from Paddington, is an ideal centre from which to explore the coast and moorland beauties of England's furthest west.

THE STONE MEN OF ST. CLEER

A thousand feet above sea level among the heather and bracken of Craddock Moor, four or five miles north of Liskeard, you may find to-day the remains of three ancient stone circles known as "The Hurlers." Antiquaries will tell you that the Druids first erected them, but the people of the countryside know better. From father to son, from grandparent to child, through long centuries, the story has been handed down of how "The Hurlers" came to be fixed in eternal stillness high up there above the little village of St. Cleer.

Exactly how long ago it was nobody knows, but it happened in those early days when pious saints were settling down in the remote parts of savage Cornwall and striving to convert the wild Cornish from their pagan ways.

Then, as even to this day, the game of Hurling—a sort of primitive Rugby football—was a popular pastime with the people. Village used to play against village, with goals perhaps four or five miles apart. And the good folk of St. Cleer were as fond of the game as any of their neighbours—so fond, in fact, that they would play it on any and every occasion, despite the admonitions of their local saint and parson, after whom the village was named.

Again and again he would notice that his little church was empty on Sunday mornings while the shouts and noise of a hard-fought Hurling match drifted across the moorland in through the open church door. Again and again he would take his flock [10]to task for their godless ways and their Sabbath-breaking games. But it was of little use. For a Sunday or two they would be penitent and attend service. Then would come a fine morning, and a challenge perhaps from the Hurlers of St. Ive or North Hill, on the other side of the moors, and the young men would decide to chance another lecture from the patient saint, and out they would go to the hillside to do battle for the honour of their parish.

But even the patience of saints comes to an end at last, and good St. Cleer saw something more than words was needed to lead his people into the right way. And so it happened one Sunday morning, in the midst of a hot tussle on Craddock Moor, the outraged St. Cleer arrived in search of his erring flock.

He bade them cease their game at once and return to church. Some of them obeyed, wandering sheepishly off down the hill; some were defiant and told the worthy man to go back to his prayers and not to come up there to spoil sport.

Then St. Cleer spoke in anger. Raising his staff he told them in solemn and awful tones that it should be as they had chosen. Since they preferred their game on the moor to their service in church, on the moor at their game they should stay for ever. He lowered his staff and to the horror of all onlookers the defiant ones were seen to be turned into stone.

Many centuries have passed since then. Time, wind and rain have weathered the stone men out of all semblance of humanity. Some have been destroyed, but most still remain as an awful example [11]to impious Sabbath profaners. And there you may see them silent and still, just as they were struck on that grim Sunday in the dark long ago.

The glorious moorland, rugged and wild, stretches all about them—a wonderful walking country, where one may escape from all cares and wander for hours amid the bracken and sweet-smelling grasses and find strange prehistoric remains seldom visited by any but the moorland sheep and the wild birds. It is a country of vast spaces and far views. You may see on one hand the Severn Sea, on the other the Channel; to the east the upstanding blue hills of Dartmoor and to the west the rugged highlands by Land's End—and then trudge back at night weary but happy to Liskeard, described as "the pleasantest town in Cornwall," and find it hard to believe that only five hours away is the toil and turmoil of London.

HOW ST. PIRAN CAME TO CORNWALL

Some sixteen hundred years ago, so tradition tells, there lived in the South of Ireland a very holy man named Piran. Such was his piety that he was able to perform miracles. Once he fed ten Irish kings and their armies for ten days on end with three cows. Men sorely wounded in battle were brought to him to be cured, and he cured them. Yet the Irish grew jealous of his power and decided he must be killed.

And so one stormy, boisterous morning the pious [13]Piran was brought in chains to the summit of a high cliff, and with a huge millstone tied to his neck his ungrateful neighbours hurled him into the raging billows beneath. This horrible deed was marked, as the holy man left the top of the cliff, with a blinding flash of lightning and a terrifying crash of thunder, and then, to the amazement of the savages who had thus sought to destroy him, a wonderful thing happened.

As man and millstone reached the sea the storm instantly ceased. The sun shone out, the waves and the wind died down, and, peering over the edge of the cliff, the wondering crowd saw the holy man, seated peacefully upon a floating millstone, drifting slowly away in the direction of the Cornish shore, some hundreds of miles to the south-east.

St. Piran's millstone bore him safely across the Atlantic waves until at length—on the fifth day of March—it grounded gently upon the Cornish coast, between Newquay and Perranporth, on that glorious stretch of sand known to-day as Perran Beach. Here the Saint landed, and, taking his millstone with him, proceeded a little distance inland and set himself to work to convert the heathen Cornish to Christianity.

He built himself a little chapel in the sands and lived a useful and pious life for many years, loved by his people, until at last, at the great age of two hundred and six, he died. Then his sorrowing flock buried him and built over his grave St. Piran's Chapel, the remains of which you can see to-day hidden away in the sandhills of the Penhale Sands.

Although Cornwall can boast many saints, St. Piran has greater right than any other to be called the patron of the Duchy. To him the Cornish in the old days attributed a vast number of good actions, among them the discovery of tin, the mining of which has for centuries formed one of the chief Cornish industries.

This came about, according to the old story, from the saint making use of some strange black stones that he found, to make a foundation for his fire. The heat being more intense than usual one day, these stones melted and a stream of white metal flowed from them.

The saint and his companion, St. Chiwidden, told the Cornish people of their discovery, and taught them to dig and smelt the ore, thus bringing much prosperity to the country, the story of which eventually reached the far-away Ph[oe]nicians and brought them in their ships to trade with the Cornish for their valuable metal.

Good St. Piran has left his name all over the wonderful country south-west of Newquay. In Perranporth, with its rocks and caves and glorious bathing beach; in St. Piran's Round, that strange old earth-work not far away; in the parish of Perranzabuloe, which means Perran in the Sands; in Perranwell, near Falmouth, and even further south in Perranuthnoe, which looks out across the waters of Mounts Bay.

But although memorials of him are to be found over most of South Cornwall, it is the district of the [15]Perran Sands, where he landed, lived and died, that is his true home. There, where the soft Atlantic breezes or the fierce winter gales sweep in to Perran Bay, you may look out over the dancing sea towards Ireland and America with nothing but Atlantic rollers between, or wander amid the waste of sand dunes that comprise the Perran Sands and breathe in health with every breath you take.

Perranporth is on the edge of these sandhills, which stretch away north-east to within four miles of Newquay—all within seven hours' journey from London.

THE LOST CHILD OF ST. ALLEN

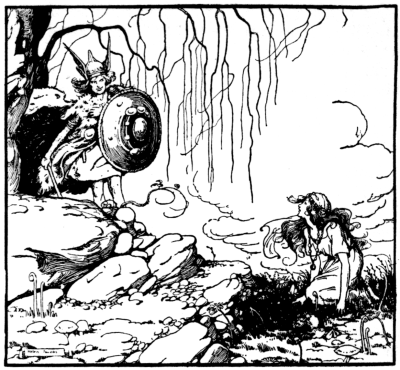

They never talk of fairies in Cornwall; what "foreigners" call fairies the Cornish call "piskies," or "small people." And all about the Duchy piskies still abound for those who are fitted to see them. The old folk will still tell you many strange stories of the piskies. One of the best known is that of the lost child of St. Allen. St. Allen is a parish on the high ground about four miles from Truro, and there, in the little hamlet of Treonike, or, as it is now called, Trefronick, on a [17]lovely spring evening years and years ago, a small village boy wandered out to pick flowers in a little copse not far from his parents' cottage.

His mother, looking from the kitchen door, saw him happily engaged in his innocent amusement, then turned to make ready the supper for her good man, whom she saw trudging home in the distance across the fields. When, a few minutes later, she went to call her boy in to his evening meal, he had vanished.

At first it was thought that the child had merely wandered further into the wood, but after a while, when he did not return, his parents grew alarmed and went in search of him. Yet no sign of the boy was discovered.

For two days the villagers sought high and low for the missing child, and then, on the morning of the third day, to the delight of the distracted parents, their boy was found sleeping peacefully upon a bed of fern within a few yards of the place where his mother had last seen him. He was perfectly well, quite happy, and entirely ignorant of the length of time that had elapsed. And he had a wonderful story to tell.

While picking the flowers, he said, he had heard a bird singing in more beautiful tones than any he had heard before. Going into the wood to see what strange songster this was, the sound changed to most wonderful music which compelled him to follow it. Thus lured onward he came at length to the edge of an enchanted lake, and he noticed that night had fallen but that the sky was ablaze with huge stars. [18]Then more stars rose up all around him, and, looking, he saw that each was in reality a pisky. These small people formed themselves into a procession, singing strange fascinating songs the while, and under the leadership of one who was more brilliant and more beautiful than the rest they led the boy through their dwelling place. This, he said, was like a palace. Crystal pillars supported arches hung with jewels which glistened with every colour of the rainbow. Far more wonderful, the child said, were the crystals than any he had seen in a Cornish mine.

The piskies were very kind to him, and seemed to enjoy his wonder and astonishment at their gorgeous cave. They gave him a fairy meal of the purest honey spread on dainty little cakes, and when at last he grew tired numbers of the small folk fell to work to build him a bed of fern. Then, crowding around him, they sang him to sleep with a strange soothing lullaby, which for the rest of his life he was always just on the point of remembering, but which as certainly escaped him. He remembered nothing more until he was awakened and taken home to his parents.

The wise folk of St. Allen maintained that only a child of the finest character ever received such honour from the small people, and that the fact that they had shown him the secrets of their hidden dwelling augured that for ever afterwards they would keep him under their especial care. And so it was; the boy lived to a ripe old age and prospered amazingly. He never knew illness or misfortune, and died at last in his sleep; and those that were near him say that as [19]he breathed his last a strange music filled the room. Some say that the piskies still haunt the woods and fields around Trefronick, but that they only show themselves to children and grown-ups of simple, trusting nature. Anyhow, those that wish to try to see them may reach the place where the lost child was spirited away in an hour and a half's walk from Truro, Cornwall's cathedral city, which is at the head of one of the most beautiful rivers in the world.

The trip from Truro down the Truro river and the Fal to Falmouth at any time of the year is a pleasurable experience that can never be forgotten. Truro is an ideal centre for South Cornwall. Wild sea coast and moorland, and woods and sheltered creeks, are all close at hand, yet the city itself has the cloistered calm peculiar to all our cathedral towns.

The tourist neglects Truro too much, for as a lover of the Duchy once said: "It is the most convenient town in Cornwall; it seems to be within an hour and a half's journey of any part of the county."

THE GIANTS WHO BUILT THE MOUNT

St. Michael's Mount, that impressive castle-crowned pyramid of rock that rises from the waters of Mounts Bay, was not always an island. In fact, it is not always an island now. At low tide you may reach it from the mainland along a causeway. But once upon a time the Mount stood in the midst of a forest; its old name, "Caraclowse in Cowse," means "the Grey Rock in the Wood," and that was at the time when the Giants built it.

Cormoran was one of the Giants; he lived in this great western forest, which is now swallowed up by the sea, and there he determined to erect for himself a stronghold that should rise well above the trees. So he set to work to collect huge stones from the neighbouring granite hills, and his new home grew apace.

But the labour of searching far afield for suitable stones, and of carrying them to the forest and piling them one upon another, was a wearying task even for a giant, and as Cormoran grew tired he forced his unfortunate Giantess wife, Cormelian, to help him in his task, and to her he gave the most toilsome of the labour.

Was there a gigantic boulder in a far part of the Duchy that Cormoran coveted, unhappy Cormelian was sent to fetch it; and she, like a dutiful wife, never complained, but went meekly about her work, collecting the finest and biggest stones and carrying them back to the forest in her apron. Meanwhile Cormoran, growing more lazy, spent much of his time in sleep, waking up only very occasionally to admonish his wife or to incite her to greater efforts.

One day, when Cormelian had been twice as far as the Bodmin moors to fetch some particularly fine stones Cormoran had seen, and was about to set off on a third journey, she, noticing her husband fast asleep, thought to save herself another weary walk by going only a short distance and breaking off some huge masses of greenstone rock which existed in the neighbourhood and placing them upon the nearly [22]completed Mount without being seen. Although Cormoran had insisted that the stone be grey, Cormelian could see no reason why one stone was not as good as another.

So, carrying out her plan, she was returning with the first enormous piece of greenstone, walking ever so carefully so as not to awaken Cormoran, when, unfortunately, he did awake. He flew into a terrible rage on seeing how his wife was trying to delude him, and, rising with a dreadful threat, he ran after her, overtaking her just before she reached the Mount.

Scolding her for her deceit, he gave her a terrific box on the ear. Poor Cormelian, in her fright, dropped the huge greenstone she was carrying, and ran sobbing from her angry husband to seek refuge in the deepest part of the forest; and it was not until Cormoran himself had finished building the Mount that she would return to him.

And to-day, as you walk along the causeway from Marazion to St. Michael's Mount, you will see on your right hand an isolated mass of greenstone, the very rock that Cormelian dropped. It is called Chapel Rock now, because years and years afterwards, when pious monks lived upon the summit of the Mount and devout pilgrims used to visit their church to pay homage at a shrine, they built a little chapel, upon poor Cormelian's green rock, of which only a few stones now remain.

You may visit Chapel Rock and St. Michael's Mount from Penzance, which is between three and [23]four miles away and is the ideal centre for some of the most wonderful scenery in Cornwall. Both Land's End and the Lizard are within easy reach of this, England's westernmost town, where a climate that rivals that of the Mediterranean may be enjoyed in the depth of winter. Semi-tropical flowers and trees bloom in the open, and in February and early March—in what is, in fact, winter weather for those in less favoured parts—Penzance and its neighbourhood are surrounded by glorious spring flowers, the growing of which forms a very considerable industry.

London and our other big towns often get their first glimpse of coming spring in the narcissi and wallflowers grown around the shores of Mounts Bay, and packed off to the grim cold cities only a few hours away.

THE TASKS OF TREGEAGLE

The name of the demon Tregeagle is a household word in nearly every part of Cornwall. His wild spirit rages of nights along the rocky coasts, across the bleak moors and through the sheltered valleys. For Tregeagle is a Cornish "Wandering Jew"; his spirit can never rest, since in life he was the most evil man the Duchy ever knew.

His story, as the legend has it, is that he was a man who amassed great wealth by robbing his neighbours [25]in the cruellest manner. As he approached the end of his most evil life remorse seized him. There was no sin he had not committed, and hoping to escape from the just reward of so wicked a life, in the hereafter, he lavished money upon the Church and the poor, trusting to obtain the help of the holy priests to save him from the clutches of the Evil One.

The priests, ever anxious to save a soul, banded themselves together, and by constant prayer and powerful exorcisms kept the powers of darkness at bay, and Tregeagle died and was buried in St. Breock Church. But the demons were not so ready to give up what they felt was their lawful prey. An important lawsuit occurred shortly after his death, and as the judge was about to give his decision against the unjustly accused defendant, to the horror of all in court, the gaunt figure of the dead Tregeagle stalked into the room. His evidence saved the defendant.

Now Tregeagle being brought from the grave, despite the honesty of his mission, placed himself once more in danger of the demons. The defendant, who had raised the spirit, calmly left him to the Churchmen to put once more to rest, and after a long conference, presided over by the Prior of Bodmin, it was decided that the only hope of ultimate peace for the evil man's spirit was that he be set to some task which might last until the Day of Judgment. And so long as he worked unceasingly at that task he might still hope for salvation.

So the task appointed him was to empty out [26]Dozmary Pool, a gloomy lake on the Bodmin Moors, with a limpet-shell with a hole in it. For years Tregeagle laboured at this, until one day during a terrible storm he ceased work for a moment. Then the demons descended upon him. He fled from his pursuers, and only escaped them by leaping right across the lake—for demons cannot cross water—and rushing for sanctuary to the little chapel on the Roche Rock, where he managed just in time to get his head in at the east window. But the howls of the demons outside, and the roaring of the terrified Tregeagle within, made the life of the unfortunate priest of the Roche chapel unbearable, and he appealed to his brethren of the Church to do something about it. So they bound the wicked spirit with holy spells and took him safely across to the north coast, where another task was set him. He was to weave a truss of sand and spin a sand rope to bind it with. But as soon as he started on his work the winds or the waves destroyed it, and the luckless creature's roars of anger so disturbed the countryside that the holy St. Petroc was prevailed upon to move him once more, to a wilder part of the country, and the saint took him to the coast near Helston.

Here Tregeagle was set to the task of carrying all the sand from the beach below Bareppa across the estuary of the Looe river to Porthleven, for St. Petroc knew that each tide would sweep the sand back again and the task could never be completed. But the demons were always watching Tregeagle, and one of them contrived one day to trip him up as he was [27]wading across the river. The sand poured from the huge sack Tregeagle was carrying and dammed up the stream, thus forming the Looe Pool, which you may see to-day just by Helston, and the Looe Bar, which separates it from the sea.

Tregeagle's next task he is engaged upon to-day. He was taken to near the Land's End, and there he is still endeavouring to sweep the sand from Porthcurnow Cove round the headland of Tol-Peden-Penwith into Nanjisal Bay, and on many a winter night if you are there you can hear him howling and roaring at the hopelessness of his task.

These scenes of Tregeagle's labours are all situated amid most glorious scenery. Dozmary Pool, bleak and lonely amid the Bodmin Moors, the little chapel on the Roche Rock near St. Austell, and the beautiful Looe Pool by Helston, that attractive little town on a hillside, which is the tourist centre for that country full of colour, deep sheltered valleys, and magnificent coast scenery, the Lizard peninsula.

Porthcurnow, the miserable man's present abode, you will find nestling amid the grim cliffs near the Land's End. And if you doubt this sad history of the demon-ridden Tregeagle, go and look at the Looe Bar and explain if you can how otherwise so strange a place could have been created.

THE LADY OF LLYN-Y-FAN FACH

Not many miles from Llandovery, in the midst of glorious mountain scenery, is a lovely little lake known as Llyn-y-Fan-Fach, the scene of a very remarkable occurrence. Once upon a time a simple cowherd, eating his frugal meal by the edge of the water, observed with amazement, seated upon the calm surface of the lake, the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. So great was his admiration for her that he cried out, and she, turning to him, gave a rapturous smile and silently disappeared beneath the waters.

The peasant was distracted, for he had fallen deeply in love with the beautiful lady. He waited until dark, but she did not appear again; but at daybreak the next morning he returned once more, and was again rewarded by the sight of his enchantress and another of her alluring smiles.

Several times more he saw her and each time he besought her to be his wife, but she only smiled and disappeared, until at length one evening, just as the sun was setting, the beautiful lady appeared, and this time, instead of diving beneath the surface, she came to the shore, and, after some persuasion, consented to marry the youth. But she made one condition: if ever he should strike her three blows without cause she would leave him, she said, and their marriage would be at an end.

So the two were married happily and went to live at Esgair Laethdy, near Myddfai, the maiden bringing with her as dowry a large number of cattle and horses which she called up from the bottom of the lake.

For years the couple lived in great prosperity and happiness, and three handsome sons were born to them; then the day arrived when husband and wife were setting out for a christening, and, being rather late, the husband slapped his wife merrily on the shoulder, urging her to hurry. Sadly she reminded him that he had struck her the first of the causeless blows.

Years passed by, and the couple were at a wedding. In the midst of all the merry-making the wife burst suddenly into tears. Patting her sympathetically on the arm, the man inquired the cause of her weeping, and she, sobbing the harder, reminded him that he had struck her a second time.

Now that he had only one chance left, the husband was particularly careful never to forget and strike the third and last blow; but, after a long while, at a funeral one day, while all were sobbing and weeping, the beautiful lady suddenly began laughing merrily. Touching her gently to quiet her, the husband realised that the end had come.

"The last blow has been struck; our marriage is ended," said the wife, now in tears; and with that she started off across the hills to their farm. There she called together her cattle and other stock, which immediately obeyed her voice, and, led by the beautiful lady, the whole procession moved off across the mountains back to the lake.

Among the animals was a team of four oxen which were ploughing at the time. They followed, too, plough and all, and, they say, to this very day you may [31]see a well-marked furrow running right across the Myddfai mountain to the edge of Llyn-y-Fan-Fach, which proves the truth of this story.

The disconsolate husband never saw his lady again, but she used sometimes to appear to her sons, and she gave them such wonderful knowledge that all three became the most famous doctors in that part of Wales.

Llandovery, from which place you may visit the scenes of this legend, is a charming little town in East Carmarthenshire, situated in glorious surroundings of mountains, vale, and moorland, where some of the finest salmon and trout fishing in South Wales may be enjoyed. It stands in the beautiful Towy Valley, on a branch line which runs up into the mountain country from Llanelly. Llandovery is famous for its air, which is said to be the purest and most bracing in the district.

ST. DAVID AND HIS MOTHER

St. David, everybody knows, is the patron saint of Wales, but few know the unique little "village-city," the smallest cathedral city in the United Kingdom, St. Davids, in the far south-west of Wales; and fewer still the story of the holy David himself. This story really begins with St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland. As the old legends tell, St. Patrick sailed on his mission to Ireland from the neighbourhood of present-day St. Davids, and he liked the look of the country so well that many years afterwards he established there a sort of missionary college known as "Ty Gwyn," or the "White House," and here on the slopes of Carn Llidi some of the earliest of the old Celtic holy men and women were educated.

Among them, some fifteen hundred years ago, was a Welsh Princess named Non, daughter of Cynyr of Caer Gawch, a powerful chieftain of the district. Non was as pious as she was beautiful. There were few maidens in the land who could compare with her.

But on what seemed to be an evil day—although it became really for Wales a very lucky one—a barbarous chieftain from the north, called Sant son of Ceredig, espied the rapturous Non picking flowers on a lonely part of the hillside, and in the manner of those boisterous times he decided to carry her off and make her his wife. And so despite her struggles the unfortunate Non was kidnapped.

After some while she managed to escape from her fierce captor and returned to live in a little cottage on the cliffs just south of St. Davids, where subsequently [34]a son was born to her. At the time of his birth they say Non clutched at a stone in the wall of her cottage room, and the marks of her fingers remained on it for ever. This stone was seen by many people for years afterwards and was eventually placed over her tomb.

The little son grew up and was baptised David by a kinsman of Non's, one St. Ailbe. Like his mother, he was sent to the "Ty Gwyn" to school and he became a very pious youth. Then he was sent away to the holy St. Illtyd to be trained as a priest.

His grandfather Cynyr, who was by no means a holy man, growing remorseful in his old age, was so much impressed by David's piety, that for the good of his soul he made over to him all his lands, and on this estate David founded a sanctuary for men of all tribes and nationalities, and, to mark the privileged ground, he caused a deep trench to be dug, and traces of this trench you may find to-day known as "The Monk's Dyke."

Here in his sanctuary the holy David lived his pious, peaceful life for many years, converting the heathen and performing miracles. And when at last he died his sorrowing companions built over his grave a great church to his memory, which years afterwards, when David had become recognised as a saint, was replaced by the wonderful old building which stands there now—St. David's Cathedral.

The remains of Non's old cottage on the cliff, which the monks afterwards turned into a Chapel, may still be seen, and because of her holy life she [35]also became a saint. Near to the ruined Chapel you will find, too, St. Non's well, or St. Nunn's well as it is sometimes called, from which the holy woman drew her water when she lived her lonely life at the time of St. David's birth.

Quaint little St. Davids lies far from a railway station, but a road motor service will take you there in a two hours' journey across magnificent country from Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire, or you may approach it along a wild, hilly road from Fishguard.

St. Davids is unique: it is literally both village and city. Situated right by the coast of picturesque St. Bride's Bay on one side and Whitesand Bay on the other, it occupies a position of peculiar beauty. Good bathing, fishing and shooting abound; there is a golf course, and, chief of its attractions, the glorious Norman architecture of its jewel-like cathedral, its ancient monastic ruins, its old cross and all the other relics of the careful work of the old ecclesiastical builders in the far-away days.

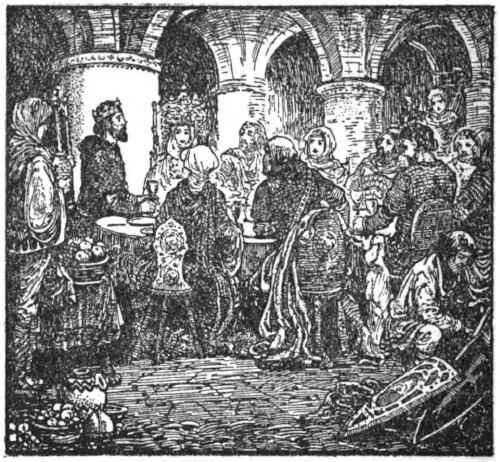

THE VENGEANCE OF THE FAIRIES

Overlooking the sea that washes the beautiful coast of the Gower Peninsula in Glamorganshire stands the ruined castle of Pennard. All about it is a waste of sandhills, beneath which, so the old stories have it, a considerable village lies buried. For it is told that in the old days, when the lands about Pennard were fertile and populous, the lord of the castle was holding a great feast one day to rejoice over the wedding of his daughter.

This happy event was being celebrated by the villagers too, and, unknown to lord or serf, by the "Tylwyth Teg," or the fairy folk who abounded in the neighbourhood, for the little people enjoy an innocent merry-making as much as do mere mortals.

And that night, long after the villagers had gone to bed, the festivities in the castle were continued. Wine flowed free and the revellers became more and more boisterous. From mere jesting they came to quarrelling, and, in the midst of their drunken orgy, there was heard an alarm. A sentry on the walls of the castle reported that he heard stealthy movements in the distance as of a large number of people approaching with care.

The frenzied warriors, fearing a surprise from their enemies, armed themselves and rushed from the castle to attack the intruders. They, too, could hear a gentle murmur in the valley below, and towards it they charged, uttering terrible threats, striking right and left with their swords at the unseen foe. But, apart from a few shadowy forms that quickly faded [38]away into the undergrowth, nothing was to be seen, and at length the knights and soldiers returned rather crestfallen, and much more sober, to their stronghold.

Now the truth of the whole matter was that the alarm had been caused by the festivities of the fairies, and they were so deeply incensed at having their party broken up by this violent intrusion of wine-maddened men that they determined to be revenged.

That very night the whole family set out for Ireland, where they descended upon a huge mountain of sand, and each one of the small people, loading himself with as much sand as he could carry, returned to Pennard and deposited it upon the village at the base of the castle, intending to bury both village and castle in sand.

To and fro the fairies went, intent upon their task of vengeance, and, when morning broke, those in the castle looked out to see what they thought was a violent sand-storm raging. By mid-day the village below the castle was overwhelmed, and those in the stronghold began to fear that it too would be smothered. But fortunately for them the Irish sand-mountain gave out, and the fairies' complete vengeance was thwarted. Still, they had destroyed the rich and valuable lands that belonged to the castle, and from that day its fortunes and those of its lords began to decline.

In proof of this story the old Irish records maintain that an extraordinary storm arose that night and blew away a whole sand-mountain.

Few tourists ever explore the beauties of the little Gower Peninsula, save holiday-makers from the neighbouring town of Swansea; yet it is a country of amazing charm, with a glorious coast and high ridges of heather and moorland. It is only about eighty square miles in extent, but it has over fifty miles of coast.

Remote from the world, this country, with its churches, castles, and many prehistoric remains, is an ideal holiday land.

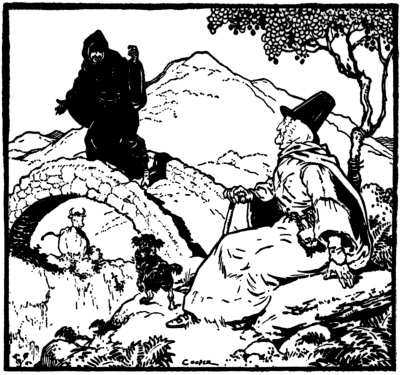

THE OLD WOMAN WHO FOOLED THE DEVIL

One of the most beautiful spots in all Wales is the Devil's Bridge—an easy excursion into the hills from Aberystwyth—which spans the gorge through which the Mynach cataract descends in four boiling leaps a distance of two hundred and ten feet. How this place received its name is an old story, which goes back to the days before the monks of sweetly named Strata Florida, who subsequently replaced the earlier bridge across the gorge.

The beginning of the story is told in an old rhyme which runs:—

"Old Megan Llandunach of Pont-y-Mynach

Had lost her only cow;

Across the ravine the cow was seen,

But to get it she could not tell how."

Such was the sad plight of old Megan, who was bemoaning the loss of her property on the wrong side of the gorge so many years ago, when there appeared to her suddenly a cowled monk, whose dark face was scarcely discernible, with a rosary hanging to his girdle, and a deep but pleasant voice.

Enquiring the cause of her distress, the monk, in sympathetic tones, promised to aid her. He would, he said, build a bridge across the ravine, so that she might recover her lost cow, if she would promise to give him the first living being to cross the bridge.

This seemed a natural enough suggestion to the sorrowing old dame, for the good monks of the neighbourhood were ever about the countryside, [42]seeking converts; so Megan agreed, and the monk set to work with amazing energy and skill to construct the bridge. And as he worked Megan sat on a boulder and watched him.

Before sundown the marvellous bridge was finished, and the smiling monk, walking over it, invited Megan to follow him and seek her cow. But Megan had been observant. She had noticed two or three things. One, that there was no cross attached to the monk's rosary; another, that while he was labouring at his building he had slipped, and his left leg was exposed through his long habit, and the knee was on the back of the leg, and not the front; also the leg ended not in a foot, but in a cloven hoof.

And cunning old Megan was taking no chances. Feeling in the pocket of her skirt she found a crust, and walking to her side of the bridge she called to a black cur that was playing about. Hurling the crust across the bridge she bade the dog fetch it. He ran over the bridge, and Megan, smiling at the monk, thanked him, and told him to take the dog as his reward.

The devil, realising that he had been fooled, disappeared in an awe-inspiring cloud of smoke and sulphur fumes; but the bridge remained, and its name to this day recalls the discomfiture of his evil plans. So, having fooled the devil, Megan was able to recover her lost cow.

Wordsworth and Borrow, among other famous writers, have immortalised the impressive beauties of the Devil's Bridge and its roaring cataract. It is [43]easily reached from that most attractive of Welsh seaside towns, Aberystwyth, and lies in a country dominated by great Plinlimmon, from the top of which a view of unrivalled beauty may be obtained.

All about this country of mountain and moorland are scenes of intense historic interest and natural beauty. It is a district bleak and bracing on the summits, warm and sheltered in the valleys, and as yet quite unspoiled by the crowd, as too is the charming town which is the centre of this country.

Aberystwyth retains the quiet charm of an old-world "watering-place," and glories in its wonderful climate and healing sea breezes that blow in across Cardigan Bay, which have won for it its reputation in winter and summer for being a British Biarritz.

THE WOMEN SOLDIERS OF FISHGUARD

They tell a story down in Pembrokeshire of how the Welsh country-women once defeated an invading army. It was in the days of the Napoleonic wars when, on a winter's afternoon, four hostile ships appeared unexpectedly off Fishguard Bay. On board were fourteen hundred soldiers intent upon an invasion of Britain.

The wild country of the far west of Wales was in those days even more remote than it is now. In the neighbourhood were but three hundred militiamen, and the invaders had an easy task in landing at Llanwnda, about two miles away from modern Fishguard, in a charming sheltered inlet known as Careg Gwastad Bay.

But the gallant Welsh determined to drive out the invader. They were furious, and, armed with scythes and other farm implements, they quickly gathered together. For such firearms as they had there was little ammunition, so they stripped the roof of beautiful little St. David's Cathedral of its lead in order to make bullets.

And the women of the country followed their men. Clad in their red cloaks and high black steeple-crowned hats, in the distance they had all the appearance of regular soldiers, and the leader of the defending forces was quick to realise this fact.

He marshalled them into something like military formation and marched them about in various places where they could be seen by the invading troops. Up and down hill the willing Welsh women trudged until darkness fell and they were tired out.

Meanwhile there was consternation in the invaders' camp. The commander knew that scarlet was the colour of our soldiers' uniform, and he could only conclude that overwhelming reinforcements were arriving from the interior. Believing his cause hopeless, he sent in a letter under a flag of truce to the British commander, offering to surrender, and within three days of landing the whole invading force was made prisoner.

There is an amazing sequel to this invasion, for it seems that most of the troops employed were criminals, released from French gaols, and other similar undesirable characters, and since they had failed in their primary object the French Government was none too anxious to have them back in France again, and refused to exchange them.

The British Government was no more pleased than the French to have so unsavoury a band of ruffians in its midst, and it had at last to force the Frenchmen to receive their own rogues back again. This was done by threatening that if the prisoners were not exchanged within a certain time they would be landed with arms on the coast of Brittany and left to do their worst.

The French preferred to have them in control and exchanges were promptly arranged, the discomfited invaders going back, it is assumed, to the safety of the French prisons from which they had been brought.

Careg Gwastad Bay, the scene of this landing, is but one of the many fascinating little inlets that [47]abound along the coast in the Fishguard neighbourhood. Excellent fishing—for sea fish, trout, sewin, and often salmon—abounds off the coast or in the streams. Fishguard is fortunate in possessing a modern steam-heated hotel close to the station—the Fishguard Bay—which is equipped with every modern luxury and comfort.

From Fishguard one can approach, too, that romantic and historic country known as Kemaes Land, which extends away to the borders of Cardiganshire, a country—bounded on the north by the cliffs that run down to the waters of Cardigan Bay—full of old churches, castles, and strange remains of earlier civilisations, standing remote upon its mountains and moorlands.

This is a land of flowers too, for its mild winter climate enables many plants to flourish in the open that must seek the security of greenhouses in the bleaker parts of the south.

HOW BALA LAKE BEGAN

There is a Welsh couplet, still well known in the neighbourhood of beautiful Bala Lake in Merionethshire, which, translated into English, runs:

"Bala old the lake has had, and Bala new

The lake will have, and Llanfor, too."

For there is an ages-old belief in the countryside that Bala will continue to grow bigger until it has swallowed up the village of Llanfor, now about a couple of miles from the water's edge.

According to the old story the site of the original town is near the middle of the present lake, at a spot opposite Llangower. There, years and years ago, a peaceful community lived a happy, prosperous life in their houses clustering around a well called Ffynnon Gwyer, or Gower's Well.

Only one very important thing had these long-ago people to remember, and that was to cover up their well every night, otherwise, as they knew from their fathers and grandfathers before them, the spirit of the well would grow angry with them and wreak some dire punishment upon them.

But one night, after some special festivities, the guardian of the well forgot his task. Too late this omission was discovered, for as soon as the last inhabitant was in bed, the well began to gush forth water.

Soon the whole village was in a state of alarm. The quickly rising waters began to flow into the cottages, and young and old rushed to Ffynnon [50]Gower, which they realised was the cause of their distress. There they saw a great stream of water gushing upward. In their anger they called upon the negligent guardian, but he, seeing the harm that had come of his forgetfulness, had fled, though it is said he did not escape the angry waters, for they overtook him and drowned him miserably.

A frenzied effort was made to cover up the well and stop the unwelcome flow, but it was useless, and the people of old Bala had to escape as best they could to higher ground. When morning broke they looked out to where their homes had been and saw, instead of their fields and houses, a great lake three miles long and a mile wide.

To-day the lake is five miles long; and they say that on clear days, when its surface is absolutely calm, you may see at the bottom, off Llangower, the ruins and chimneys of the old town that was overwhelmed so long ago.

And, as the old couplet tells, they say too that the spirit of Gower's Well is not yet appeased. On stormy days water appears to ooze up through the ground at new Bala, which is built at the lower end of the lake, and some day they believe that too will be swamped and the waters will cover the valley as far down as Llanfor.

Llyn Tegid is the old name for Bala Lake; it means the lake of beauty, and Bala well deserves that title. Its shores are verdant and beautifully wooded, commanding in many places magnificent distant views of the mountains which encircle it only a few miles [51]away. Its waters teem with fish; trout up to fourteen pounds and pike twice as big have been caught there—but the flyfisher must not expect always such giants. There is salmon-fishing to be had in the Treweryn river in September.

In the neighbourhood are places of wonderful beauty. Dolgelly, nestling beneath great Cader Idris, is easily accessible, as also is that charming seaside town of Barmouth. Bwlch-y-Groes, one of the finest mountain passes in the Principality, is only ten miles away, and an easy excursion takes one across another very beautiful pass to Lake Vyrnwy, which gives to Liverpool its splendid water supply, and provides anglers with magnificent baskets of Loch Leven trout.

All around is a paradise for artists and fishermen, and a country rich in mountain streams, wild woods, and wide, far views unbeaten in any part of Wales.

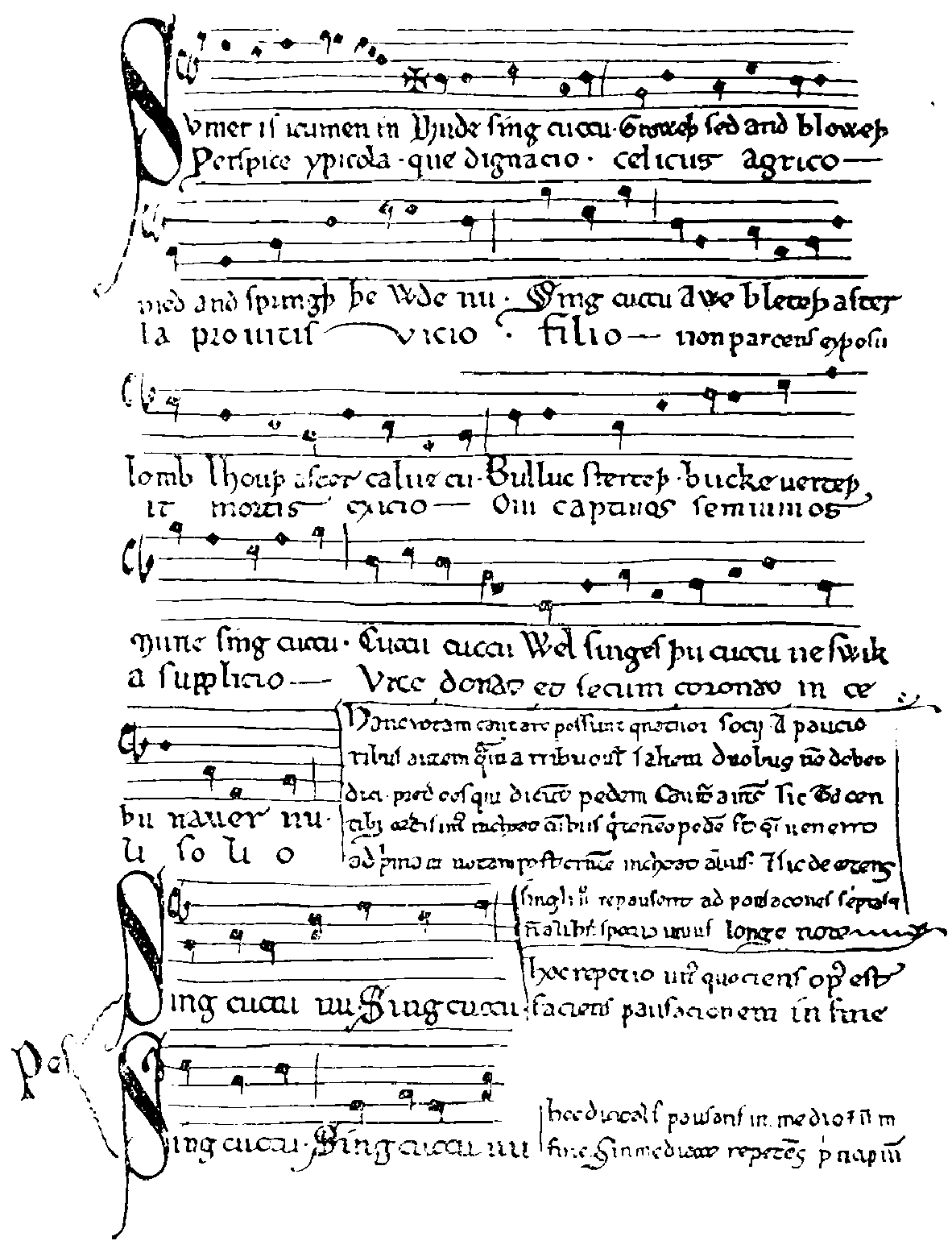

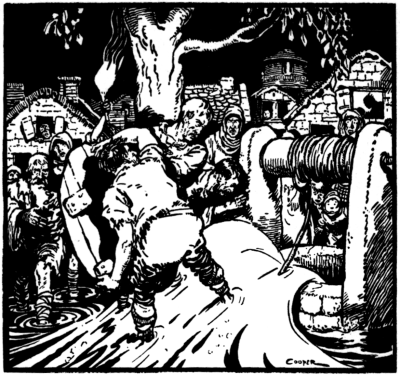

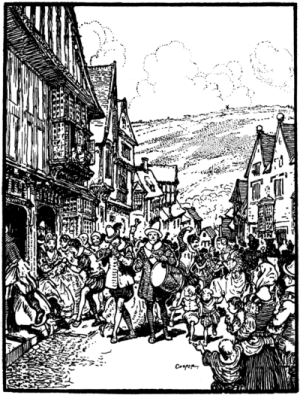

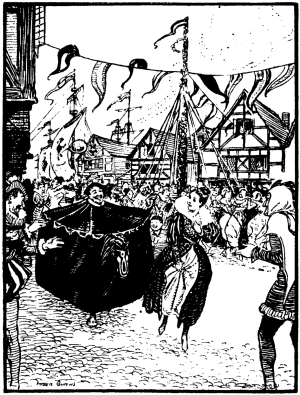

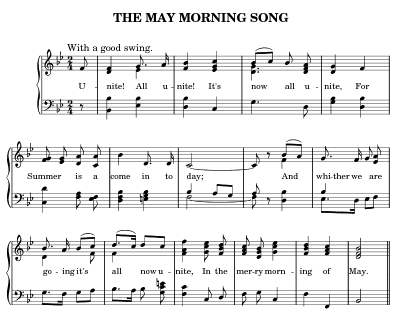

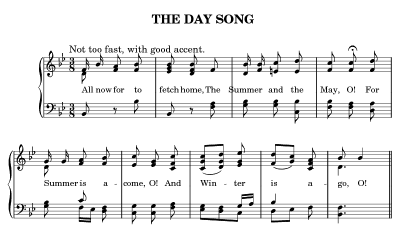

THE FURRY DAY SONG

The celebration of "Furry Day," on May 8th each year, at Helston, in South Cornwall, is one of the most interesting survivals of an old custom in the whole country. On "Furry Day" the whole town makes holiday. The people go first into the surrounding country to gather flowers and branches, and return about noon, when the Furry dance begins and continues until dusk; the merrymakers, hand in hand, dancing through the streets and in and out of the houses, the doors of which are kept open for the purpose.

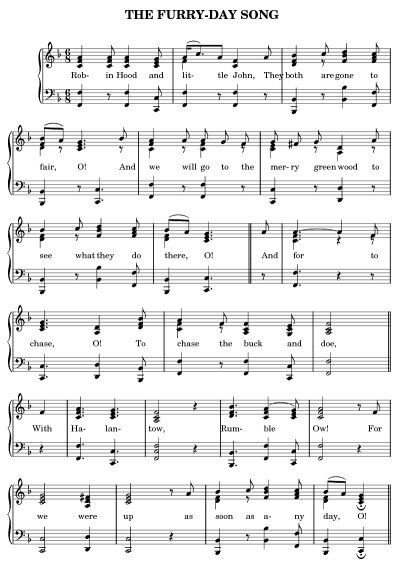

The origin of the word "Furry," and of the song and dance, is lost in the ages. Some authorities hold that these celebrations are a survival of the old Roman Floralia, others that it began in celebration of a great victory gained by the Cornish over the Saxons. The words and music, as they have come down to us, show many signs of Elizabethan origin. The music reproduced here is from a very old setting and contains many crude harmonies unfamiliar at the present day.

There is one line of the song, "God bless Aunt Mary Moses," that most people will find incomprehensible. It refers to the Virgin Mary, "Aunt" being among the Cornish a term of great respect; "Moses" being a corruption of the old Cornish word "Mowes," a maid. "Mary Moses" means literally "Mary the Maid."

(Listen to MIDI version of the above)

Sheet Music: Page 1, Page 2.

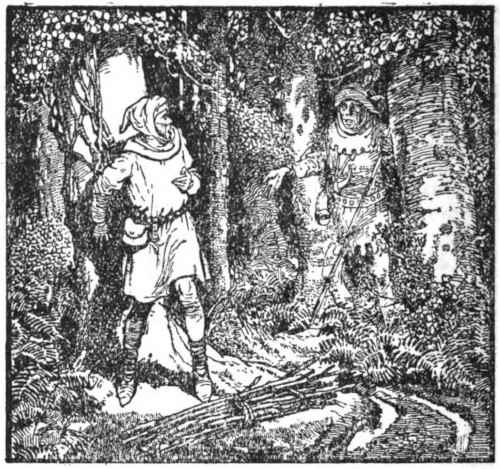

Robin Hood and little John,

They both are gone to fair, O!

And we will go to the merry green wood

To see what they do there, O!

And for to chase, O!

To chase the buck and doe.

With Halantow,

Rumble Ow!

For we were up as soon as any day, O!

And for to fetch the Summer home,

The Summer and the May, O!

For Summer is a-come, O!

And Winter is a-gone, O!

Where are those Spaniards,

That make so great a boast, O?

They shall eat the grey goose feather,

And we will eat the roast, O,

In every land, O,

The land where'er we go.

With Halantow, &c.

As for Saint George, O,

Saint George he was a Knight, O!

Of all the Knights in Christendom,

Saint Georgy is the right, O!

In every land, O,

The land where'er we go.

With Halantow, &c.

God bless Aunt Mary Moses,

And all her powers and might, O,

And send us peace in merry England,

Both day and night, O,

And send us peace in merry England,

Both now and evermore, O!

With Halantow, &c.

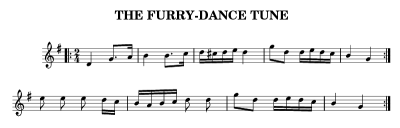

(Listen to MIDI version of the above)

Sheet Music: Page 1.

The simple air only of "The Furry Dance" is given here. It was probably originally played by a musician on the pipe, accompanying himself on the tabor.

Remote Cornwall is still full of queer old customs and survivals of other days. Helston, the "Metropolis" of that picturesque wild district near the Lizard, forms a perfect setting for this interesting relic of the past, and an ideal centre for those who wish to enjoy the beauties and mystery of one of the most remote corners of our island.

LEGEND LAND

Being a collection of some of the

OLD TALES told in those Western

Parts of Britain served by the

GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY, now

retold by LYONESSE

VOLUME TWO

Published in 1922 by

THE GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY

[FELIX J. C. POLE, GENERAL MANAGER]

PADDINGTON STATION, LONDON

CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

This is a reprint in book form of the second series of The Line to Legend Land leaflets, together with a Supplement, "The Padstow May Day Songs."

The Map at the beginning provides a guide to the localities of the six Devon legends; that at the back to those of Cornwall.

Printed by Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Company Limited,

One New Street Square, London, E.C.4

FOREWORD

The western parts of our country are richer in legend than any other part. Perhaps this is because of the Celtic love of poetry and symbolism inherent in the blood of the people of the West; perhaps because of inspiration drawn from the wild hills and bleak moors of the lands in which they live; perhaps because life is, and always was, quieter there, and people have more time to remember the tales of other days than in busier, more prosaic, districts.

Most of the Devon legends cluster around the grim wastes of Dartmoor, and, like that wonderful stretch of country, are wild and awe-inspiring. The devil and his wicked works enter largely into them, and there is reason to believe them to be among the oldest tales known to us. Possibly they were not new when the hut circles of the Moor were inhabited and Grimspound was a busy village.

Some of the Cornish stories told in this series, like the story of Lyonesse and of Parson Dodge and the Spectre Coach, have their beginning in historical fact; yet into the latter story has been woven a tale that is centuries older, in origin, than the days of the eccentric priest of Talland.

But old tales, like old wine, need nothing but themselves to advertise them. In their time they have entertained—who can say how many hearers through the ages? And they are still good—read or told—to amuse as many more.

LYONESSE

THE CHURCH THE DEVIL STOLE

Most travellers to the West know queer little Brent Tor, that isolated church-crowned peak that stands up defiantly a mile or two from Lydford, seeming, as it were, a sentry watching the West for grim Dartmoor that rises twice its height behind it. Burnt Tor, they say, was the old name of this peak, because, seen from a distance, the brave little mountain resembles a flame bursting upwards from the earth. Others—with less imagination and perhaps more knowledge—would have us believe that Brent Tor was once a volcano, and that it really did burn in ages long since.

But the old folk of the neighbourhood care less for the name of their Tor than for the strange story of the church that crowns its summit.

Ever so long ago, they will tell you, the good folk of the lower lands around the foot of the hill decided to build themselves a church. They had long needed one; so long that the Devil, who roamed about Dartmoor, had begun to consider that such an irreligious community was surely marked down for his own.

That is why, when he came upon the people one day setting to work to build a church, he was overcome with fury.

But he seems to have thought it all out carefully, and to have decided to let them go on for a while, and so, week after week, at the foot of Brent Tor, the little church grew.

At last it was finished, and the good folk were preparing great festivities for its dedication when, during one dark autumn night, the church disappeared.

In the greatest distress they bemoaned their sad plight, but they were quick to attribute the evil action to the Prince of Darkness, and to show him that they were not to be intimidated they decided to begin at once to build another church. Throughout the day they made their plans, and retired to rest that night determined to start on their pious work next morning.

But when they woke in the morning they saw with amazement their own church perched high on the hill above them. The Devil had stolen it, and to mock the villagers had replaced it on the hilltop, where, he thought, having dominion over the powers of the air, he would be able to defeat their designs.

The people, however, thought otherwise. They sent in haste for the nearest bishop, and with him proceeded to the top of Brent Tor. And, since St. Michael looks after hilltops, to him they dedicated their church.

Hardly had the service finished when the Devil, passing by, looked in to jeer, as he thought, at the foolish folk he had deceived. But on the summit of the Tor he met St. Michael.

The Archangel fell upon the Evil One and tumbled him straightway down the hill; then, to make sure of his discomfiture, hurled a huge rock after him. And there at the base of Brent Tor you may see the very rock to this day.

If you climb to the top of the hill you will get, on a fine day, one of the most beautiful views in the West. On one side is Dartmoor in all its rugged [7]glory; on the other, distant, blue and mysterious, the uplands of the Bodmin moors.

Lydford, from which you can best reach Brent Tor, is famous for its wild gorge. It stands on the edge of Dartmoor itself, and from it country of wonderful beauty may easily be reached. All around are hills and heather-carpeted moorland; yet a short railway journey will take you from this far-away village to busy Plymouth, Okehampton, or Launceston, the border town of Cornwall.

Here, where winds sweep from any direction across great wastes of moor, or from the sea, health and quiet are to be found more easily than in any popular holiday resort or fashionable spa.

THE PARSON AND THE CLERK

All real old stories of long ago should begin with "Once upon a time," and so, once upon a time there was a Bishop of Exeter who lay very ill at Dawlish, on the South Devon coast, and among those who visited him frequently was the parson of an inland parish who was ambitious enough to hope that, should the good bishop die, he would be chosen to fill his place.

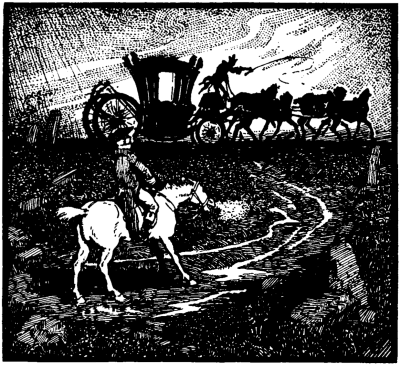

This parson was a man of violent temper, and his continued visits to the sick man did not improve this, for his journey was a long and dreary one, and the bishop, he thought, took an unconscionable time in dying. But he had to maintain his reputation for piety, and so it happened that on a winter night he was riding towards Dawlish through the rain, guided, as was his custom, by his parish clerk.

That particular night the clerk had lost his way, and, long after he and his master should have been in comfortable quarters at Dawlish, they were wandering about on the high rough ground of Haldon, some distance from the village. At last, in anger, the parson turned upon his clerk and rebuked him violently. "You are useless," he said; "I would rather have the devil for a guide than you." The clerk mumbled some excuse, and presently the two came upon a peasant, mounted upon a moor pony, to whom they explained their plight.

The stranger at once offered to guide them, and very soon all three had reached the outskirts of the little coast town. Both parson and clerk were wet through, and when their guide, stopping by an old, tumble-down house, invited them to enter and take some refreshment, both eagerly agreed. They entered the house and found there a large company of wild-looking men engaged in drinking from heavy black-jacks, and singing loud choruses. The parson and his servant made their way to a quiet corner and enjoyed a good meal, then, feeling better, agreed to stay for a while and join their boisterous companions.

But they stayed for a very long while. The drink flowed freely and both grew uproarious, the parson singing songs with the best of the company and shouting the choruses louder than any. In this manner they spent the whole night, and it was not until dawn broke that the priest suggested moving onward. So none too soberly he called for the horses.

At this moment the news arrived that the bishop was dead. This excited the parson, who wished at once to get to work to further his ambitious designs, so he pushed the clerk into the saddle and hastily mounted himself. But the horses would not move. The parson, in a passion, cried, "I believe the devil is in the horses!"

"I believe he is," said the clerk thickly, and with that a roar of unearthly laughter broke out all around them. Then the now terrified men observed that their boisterous friends were dancing about in glee and each had turned into a leering demon. The house in which they had passed the night had completely disappeared, and the road in which they stood was transformed into the sea-shore, upon which huge waves were breaking, some already submerging the clerk.

With a wild cry of terror the parson lashed once more at his horse, but without avail. He felt himself growing stiff and dizzy—and then consciousness passed from him.

Neither he nor his clerk ever returned to their parish, but that morning the people of Dawlish saw two strange red rocks standing off the cliffs, and later, [11]learning this story, they realised that the demons had changed the evil priest and his man into these forms.

Time and weather have wrought many changes in the Parson and Clerk Rocks, not the least curious being to carve upon the Parson Rock the semblance of the two revellers. From certain positions you may see to-day the profiles of both men, the parson as it were in his pulpit, and the clerk at his desk beneath him.

The red cliffs around Dawlish make the place peculiarly attractive at first sight, and the attraction is not lessened by familiarity with the town. It enjoys the best of the famous South Devon climate; warm in winter and ever cooled by the sea breeze in summer, it is an excellent holiday centre. Historic Exeter is close at hand and Dartmoor within afternoon excursion distance.

THE WEAVER OF DEAN COMBE

About a mile outside Buckfastleigh, on the edge of Dartmoor, a little stream, the Dean Burn, comes tumbling down from the hills through a narrow valley of peculiar beauty. A short distance up this valley a waterfall drops into a deep hollow known as the "Hound's Pool." How this name arose is an old story.

According to the legend, hundreds of years ago, there was living in the neighbouring hamlet of Dean Combe a wealthy weaver named Knowles. He was famous throughout those parts of Devon for his skill and industry. But in due course he died and was buried.

On the day after the funeral, hearing a strange noise, Knowles' son ran to his father's work-room, where, to his alarm, he saw the dead man seated at his loom working away just as he had done day after day, year after year, in life. In terror the young man fled from the house, and sought the parson of Dean Prior.

The good priest was at first sceptical, but he returned with the frightened man to the house. As soon as the two had entered the door the parson's doubts vanished, for sure enough, from an upper chamber, came the familiar, unmistakable sound of the loom at work.

So the parson went to the foot of the staircase and shouted to the ghostly weaver: "Knowles, come down! This is no place for thee."

"In a minute, parson," came the reply; "just wait till I've worked out this shuttle."

"No," said the parson, "come thee at once; thou hast worked long enough on this earth."

So the spirit came down, and the parson led it outside the house. Then taking a handful of earth, which he had previously secured from the churchyard, he flung it into the ghost's face, and instantly the weaver turned into a black hound.

"Now, follow me," the parson commanded; the grim dog obediently came to heel. The pair then proceeded into the woods, which, so they say, as soon as the two entered, were shaken by a violent whirlwind. But at last the priest led his charge to the edge of the pool below the waterfall, then producing a walnut-shell with a hole in it, handed it to the hound and addressed it.

"Knowles," he began, "this shows me plainly that in life thou tookest more heed of worldly gain than of immortality, and thou didst bargain with the powers of evil. There is but one hope of rest for thee. When thou shalt have dipped out this pool with the shell I have given thee, thou shalt find peace, but not before. Go, work out thy salvation."

With a mournful howl that was heard as far as Widdicombe in the Moor, the hound leapt into the pool to begin its hopeless labour, and there, exactly at midnight or midday, they say, you may still see it at its task.

Buckfastleigh is on a branch line that runs up from Totnes, skirting Dartmoor, to Ashburton. All around is some of the most glorious scenery in Devon. Buckfast Abbey, founded in 1148 and for centuries a [15]ruin, was purchased by French Benedictines in 1882, and is now a live and busy monastery once again.

Just beyond Dean Combe is Dean Prior, a place of the greatest literary interest, for it was the home of the poet Herrick for many years.

The country all about abounds in objects of beauty and interest, yet is all too often neglected by the holiday-maker at the neighbouring seaside towns a few miles away, or the scurrying motorist speeding down along the Plymouth road.

THE DEMON WHO HELPED DRAKE

All the demons of whom the old folks tell in the West Country were not evil spirits. Some, like that one who helped Sir Francis Drake, worked good magic for the benefit of those to whom they attached themselves.

To Drake's demon a number of good deeds are attributed. One story they tell of him is of those days when the news of the fitting out of the mighty Spanish Armada had caused a thrill of apprehension to sweep through the country. The danger that threatened was very great, and Drake, like all of those who were charged with the safeguarding of our shores, was vastly worried, although he kept his worries to himself.

And one day, as the story goes, the great admiral was sitting, weighed down with anxiety, making and remaking his plans, on Devil's Point, a promontory that runs out into Plymouth Sound. As he was thinking, almost unconsciously he began whittling a stick. How, he wondered, could he find enough ships to combat the enormous force the King of Spain was sending against him?

Looking up from his reverie, at length, across the Sound, he started in happy surprise, for floating quite close to the shore he saw a number of well-armed gunboats; each chip that he had cut from the stick having been so transformed by the magic of his friendly demon.

Later, when Drake had achieved his great victory over the Spaniards, Queen Elizabeth gave him [18]Buckland Abbey. When he took possession, the legend goes, there was great need for stables and outhouses, and building work was set in train at once.

After his first night there, one of Drake's servants was amazed to find how much building had been done, and, feeling that something unusual must be going on during the hours of darkness, he secreted himself in a tree at dusk the next evening to see what happened. There he fell asleep, but towards midnight he was awakened by the tramp of animals and the creaking of wheels. Looking down, he saw several ox teams approaching, each dragging a wagon filled with building materials and led by a weird spectre form.

As the first team passed by, the spectre, urging the weary beasts on, plucked from the earth the tree in which the servant was hiding, in order to beat them. The unfortunate servant was cast to the ground, and, picking himself up, ran in terror to the house.

His violent fall injured him seriously, and they say that the fright made him half-witted for the rest of his life. Still, he recovered sufficiently to tell others of what he had seen, and to explain the mystery of the miraculous speed with which Buckland Abbey's outbuildings were constructed.

Buckland Abbey lies between Plymouth and Tavistock, close to the banks of the pretty River Tavy. Drake built his house there on the site of a thirteenth-century abbey, some remains of which are still to be found.

Preserved in Buckland Abbey is Drake's Drum, the beating of which in time of national danger would, so they say, bring the great Elizabethan sailor back from his ocean grave by the Spanish Main to fight once more for his country.

Plymouth, the port with which Drake is so closely associated, is a town brimful of interest, magnificently situated on high ground overlooking the sea. From famous Plymouth Hoe, the scene of the historic game of bowls, a view of unequalled charm may be obtained. Out at sea, the Eddystone Lighthouse is seen, and east and west the rugged shores of the Sound, always alive with shipping, meet the eye.

And although Plymouth is over 226 miles from London, it is the first stopping-place of the famous Cornish Riviera Express, which leaves Paddington each week-morning at 10.30 and arrives at Plymouth only four hours and seven minutes later.

THE SAMSON OF TAVISTOCK

In the beautifully situated old town of Tavistock there lived, just over a thousand years ago, a man of huge stature and great strength named Ordulph, of whom some strange stories are told. Ordulph was the son of Orgar, the then Earl of Devon, who was the founder of Tavistock's wonderful old abbey. Some of Ordulph's huge bones may be seen to-day in a chest in Tavistock church, to which place they were taken when his gigantic coffin was discovered beneath the abbey ruins many years ago.

As the old stories go, Ordulph used at times to amuse himself by standing with one foot on either side of the River Tavy, having previously ordered his men to organise a great drive of wild beasts from the Dartmoor forests above the town. The animals he caused to be driven between his legs, while he, stooping down, would slay them with a small knife, striking their heads off into the running stream.

On one occasion, they say, he rode to Exeter with King Edward of the Saxons. When the two with their retinue arrived before the city and demanded admission, there was some delay in throwing open the gates.

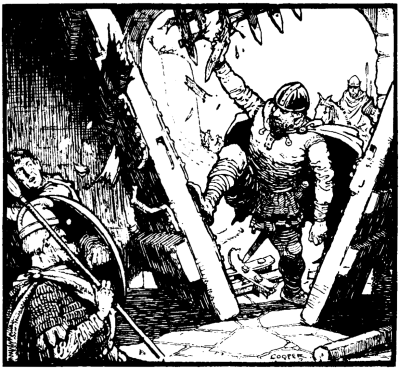

This Ordulph took as an affront to the King, and, leaping from his enormous black charger, he approached the portcullis and with his hand tore the ponderous thing from its sockets and broke it into small pieces.

Then, striding up to the strong iron-bound gates, with a kick he burst open bolts and bars, and proceeded [22]to lift the gates from their hinges. After that, with his shoulder he pushed down a considerable portion of the city walls, then strode across the ruins he had made into the now terrified city, and bade the alarmed townsfolk to be more careful next time to receive their King properly, lest worse things should happen to them.

King Edward, they say, was as much concerned as the citizens of Exeter about this stupendous exhibition of strength displayed by his companion. He was fearful at first that so violent a man must be in league with the devil; but apparently he was satisfied that this was not the case, for Ordulph lived a very pious life in his latter years, and contributed large sums to the endowment of the abbey his father had founded.

Tavistock still retains many remains of its once mighty abbey. The town, situated as it is in a picturesque valley through which the beautiful Tavy rushes, crystal clear, from the moors, is one of the most attractive in all Devon. It is the finest centre for exploring the western part of Dartmoor, for the moorland creeps down to within a short walking distance of the town itself.

Fine fishing may be had in the neighbouring streams, there is a good golf course, and the country all around abounds in objects of great natural beauty and historic interest.

Exeter, the cathedral city which was the scene of Ordulph's Samson-like feat, is thirty-three miles away by a road that crosses the very heart of Dartmoor, a wild, beautiful highway that rises in places to [23]well over 1,200 feet; and sixteen-and-a-half miles to the south is Plymouth, from which Tavistock is easily reached by train.

There are few places in the West Country more attractive than this old town in the moors, so richly endowed by time and by nature.

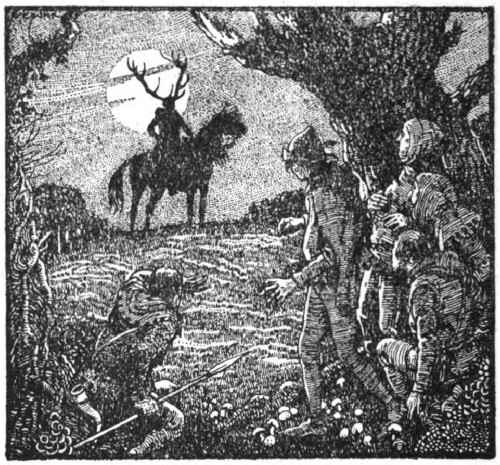

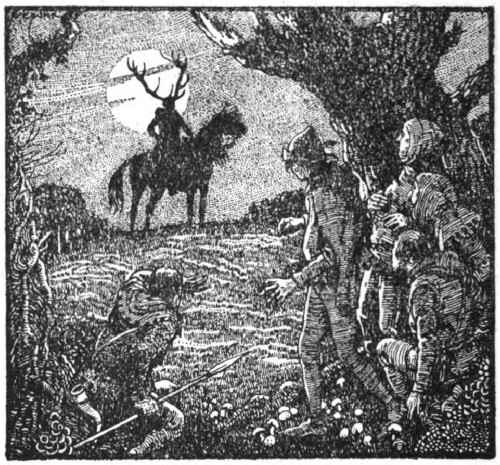

THE MIDNIGHT HUNTER OF THE MOOR

Running across the southern part of the heart of wild Dartmoor is a very ancient road. "The Abbot's Way" they call it, and antiquaries hold varied opinions as to when it was made, and even as to where it led to and from. To-day, much of this old trackway has gone back to nature and cannot be distinguished from the rugged moorland across which it passes, but some [25]stretches of it survive in a strange green path marked here and there by a boundary stone or a much-weathered Celtic cross.

But the old stories—tales perhaps even older than the road—tell that the Abbot's Way is the favourite hunting ground of the Wish Hounds or Yell Hounds, an eerie spectre-pack that hunts across the wildest parts of the moor on moonless nights.

Strange, gruesome tales are told by those who, benighted or lost in the fog, have stumbled home through the dark of a winter night across the grim moorland. They tell—half dazed with fear—as they reach at last some house and welcome human companionship, of the wild baying of the hounds that drifted through the murk night to their ears, or of the sudden vision of the pack passing at whirlwind speed across bog and marsh urged onward by a grim black figure astride a giant dark horse from whose smoking nostrils came flame and fire.

The description of this figure, "The Midnight Hunter of the Moor," seldom varies, although stories of the Wish Hounds differ from time to time.

Some say that they are headless, and that their blood-curdling cries seem to emerge from a phosphorescent glow of evil smoke that hovers about the place where the head should be. Others describe them as gaunt, dark beasts with huge white fangs and lolling red tongues.

Up on the grim wild moors it is not hard at midnight, through the roaring of the wind, or in the stillness of a calm night broken only by the weird cry [26]of some nocturnal bird or the distant sound of a rushing stream, to imagine, far away, the baying of this spectre-pack.

The old country folk hold that the man or beast who hears the devilish music of the Wish Hounds will surely die within the year, and that any unhappy mortal that stands in the way of the hunt will be pursued until dawn, and if caught will inevitably lose his soul; for the dark huntsman, they say, is the devil, whose power is great over that rugged country between sunset and sunrise.

Even to-day some of the older people will tell you stories of escapes they have had from the Midnight Hunter, or of the fate that befell some friend or neighbour very many years ago who never returned from a night journey across the moor.

But grim as it may be after nightfall, the country which the Abbot's Way traverses is one of amazing beauty. You may pick up this old track on the moors a mile or two from Princetown, or strike north to join it from South Brent or Ivybridge station. To the west there is a stretch of it clearly marked near Sheepstor where it crosses the head-waters of the Plym.

Some think the old Way got its name because it was the means of communication between the Abbeys of Buckfast on one side of the moor and Tavistock on the other. Others say it was an old wool-trading track to the west.

Dartmoor all around this district is at its best. It is a riot of rugged boulder, fern, and heather, through which rushing streams, full of trout, flow swiftly [27]southward to the Channel. The Tors here are not the highest of the moor, yet many of them rise well above the 1,500 feet level.

It is a country easy of access, for the Great Western main line skirts the southern edge of Dartmoor between Totnes and Plymouth, and railway and coaching services enable the tourist to visit some of the most remote parts of the moor in a day trip from Torquay, Dartmouth, Teignmouth, or in fact any of the South Devon seaside resorts between Dawlish and Plymouth. But the visitor who wishes to explore Southern Dartmoor at leisure will find Newton Abbot the most convenient centre.

THE LOST LAND OF LYONESSE

There is a lot of truth mingled with the old legends that tell of the lost land of Lyonesse, a fertile and prosperous country that once extended west from Cornwall as far as the Scillies. According to those old traditions a vast number of villages and 140 churches were overwhelmed on that day, over eight hundred years ago, when the angry sea broke in and drowned fertile Lyonesse, and now, as an old rhyme has it:

"Beneath Land's End and Scilly rocks

Sunk lies a town that Ocean mocks."

On that fatal day, November 11, 1099, a mighty storm raged all about our coasts, but the gale was of unparalleled severity in the West. Those who have seen a winter gale blowing across the sea that now flows above the Lost Land will know that it is very easy to believe that those giant angry waves could break down any poor construction of man's hand intended to keep the wild waters in check.

For Lyonesse, they say, was stolen by the sea gradually. Here a bit and there a bit would be submerged after some winter storm, until came this grim November night, when the sea made a clean sweep of the country and rushed, with stupendous speed, across the flat wooded lands until it was brought to a halt by the massive cliffs of what is now the Land's End peninsula.

There was a Trevilian, an ancestor of the old Cornish family of that name, who only just escaped with his life from this deluge. He had foreseen what was coming and had removed his farm stock and his [30]family from his Lyonesse estate, and was making one further journey to his threatened home when the sea broke in upon it. Trevilian, mounted on his fleetest horse, just beat the waves, and there is a cave near Perranuthnoe which, they say, was the place of refuge to which the sturdy horse managed to drag his master through the angry waters.