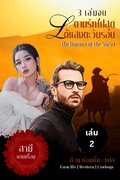

The Golden Slave

POUL ANDERSON

Cordelia lay on the couch before him.

Light rippled along her gown of sheerest silk, and her flesh seemed to glow through.

Beside her the table bore wine and food prepared for two.

Eodan gaped.

"Hail Cimbrian," Cordelia raised her hand and beckoned him. "Come," she said.

Eodan swayed toward her, the blood roaring in his temples.

"Will you drink with me?" she asked softly.

"Yes," he answered thickly.

Their hands touched as she poured the wine into his goblet, and he felt his flesh leap with excitement.

"My husband was wrong to set a king to work in his fields," she murmured. "Perhaps we two can reach a better understanding."

She lifted her goblet. "To our tomorrows, may they be better than our yesterdays."

They drank in turn.

Suddenly her arms went around him and her mouth was hot on his. "I meant this to be leisurely with much fine play," she whispered. "But that would be wrong with you. I see it now."

100 B.C.

The Cimbrian hordes galloped across the dawn of history and clashed in screaming battle against the mighty Roman legions.

Led by their chief, Boierik, and his son, Eodan, the hungry and homeless pagan tribes hurled back the Romans time after time in their desperate search for land. But for all the burning towns, the new-caught women weeping, the wine drunk, the gold lifted, the Cimbri did not find a home.

And now it was over. At Vercellae the Roman armies shattered them completely. Only a few survived—and for them death would have been more merciful.

Eodan, the proud young chieftain, had been caught and sold into slavery, his infant son murdered and his beautiful wife, Hwicca, taken as a concubine.

But whips and slave chains could not break the spirit of this fiery pagan giant who fought, seduced and connived his way to a perilous freedom to rescue the woman he loved.

The Golden Slave

I

The night before the battle, there were many watchfires. As he walked from the Cimbri, out into darkness, Eodan saw the Roman camp across the miles as a tiny ring of guttering red. Now the search has ended, he thought; this earth we shall have tomorrow, or be slain.

He thought, while his blood beat swiftly, I do not await my death.

Only the ghostliest edge of a moon was up, and the stars seemed blurred after the mountain sky. He felt Italy's air as thick. And the ground underfoot was dusty where tens of thousands of folk, their horses and cattle, had tramped over ripening grain. A poplar grove nearby stood unmoving in windless gloom. Suddenly, sharp as a thrown war-dart, Eodan recalled Jutland, Cimberland—great rolling heathery hills and storm-noisy oaks, a hawk wheeling in heaven and the far bright blink of the Limfjord.

But that was fifteen years ago. His folk, angry with their gods, had wandered since then to the world's edge. And now the Cimbrian bull must meet for one last time that she-wolf they said guarded Rome. It was unlucky to call up forsaken places in your head.

Besides, thought Eodan, this was good land here. He could make it a pastureland of horses ... yes, he might well take his share of Italy on the Raudian plain, beneath the high Alps.

The night was hot. He rested his spear in the crook of an arm while he took off his wolfskin cloak. Under it he wore the legginged coarse breeches of any Cimbrian warrior; but his shirt was red silk, made for him by Hwicca from a looted bolt of cloth. The twining leaves and leaping stags of the North looked harsh across its shimmer. He wore a golden torque around his neck, gold rings on his arms and a tooled-leather belt heavy with silver god-masks. The dagger it held bore a new hilt of ivory on the old iron blade. The Cimbri had reaved from many folk, until their wagons were stuffed with wealth. Yet it was only land they sought.

There was not much more air to be found beyond the watchfires than within the camp. And it was hardly less full of noise here: the cattle lowed enormously outside the wagons, one great clotted mass of horned flesh. Eodan remembered Hwicca and turned back again.

A guard hailed him as he passed. "Hoy, there, Boierik's son, are you wise to go out alone? I would have scouts in the dark, to slice any such throat that offered itself."

Eodan grinned and said scornfully, "How many miles away would you hear a Roman, puffing and clanking on tiptoe?"

The warrior laughed. A Cimbrian of common mold, the wagons held thousands like him. A big man, with heavy bones and thews, his skin was white where sun and wind and mountain frosts had not burned it red, his eyes were snapping blue under shaggy brows. He wore his hair shoulder length, drawn into a tail at the back of the head; his beard was braided, and his face and arms showed the tattoo marks of tribe, clan, lodge or mere fancy. He bore an iron breastplate, a helmet roughly hammered into the shape of a boar's head and a painted wooden shield. His weapons were a spear and a long single-edged sword.

Eodan himself was taller even than most of the tall Cimbri. His eyes were green, set far apart over high cheekbones in a broad, straight-nosed, square-chinned face. His yellow hair was cut like everyone else's, but like most of the younger men he had taken on the Southland fashion of shaving his beard once or twice a week. His only tattoo was on his forehead, the holy triskele marking him as a son of Boierik, who led the people in wandering, war and sacrifice. The other old ties, clan or blood brotherhood, had loosened on the long trek; these wild, youthful horsemen were more fain for battle or gold or women than for the rites of their grandfathers.

"And besides, Ingwar, there is a truce until tomorrow," Eodan went on. "I thought everyone knew that. I and a few others rode with my father to the Roman camp and spoke with their chief. We agreed where and when to meet for battle. I do not think the Romans are overly eager to feed the crows. They won't attack us beforehand."

Ingwar's thick features showed a moment's uneasiness in the wavering firelight. "Is it true what I heard say, that the Teutones and Ambrones were wiped out last year by this same Roman?"

"It is true," said Eodan. "When my father and his chiefs first went to talk with Marius, to tell him we wanted land and would in turn become allies of Rome, my father said he also spoke on behalf of our comrades, those tribes which had gone to enter Italy through the western passes. Marius scoffed and said he had already given the Teutones and Ambrones their lands, which they would now hold forever. At this my father grew angry and swore they would avenge that insult when they arrived in Italy. Then Marius said, 'They are already here.' And he had the chief of the Teutones led forth in chains."

Ingwar shuddered and made a sign against trolldom. "Then we are alone," he said.

"So much the more for us, when we sack Rome and take Italy's acres," answered Eodan gaily.

"But—"

"Ingwar, Ingwar, you are older than I. I had barely seen six winters when we left Cimberland; you were already a wedded man. Must I then tell you of all we have done since? How we went through forests and rivers, over mountains, along the Danube year after year to Shar Dagh itself ... and all the tribes there could not halt us—we reaped their grain and wintered in their houses and rolled on in spring, leaving their wives heavy with our children! How we smote the Romans at Noreia twelve years ago, and again eight and four years ago—besides all the Gauls and Iberians and the Bull knows how many others that stood in our way—how we pushed one Roman army before us across the Adige, when they would bar Italy—how this is the host they can hope to raise against us, and we outnumber it perhaps three men to one!"

The victories rushed off Eodan's tongue, a river in springtime flood. He thought of one Roman tribune after the next, tied like an ox to a Cimbrian wagon, or stark on a reddened field among his unbreathing legionaries. He remembered roaring songs and the whirlwind gallop of Cimberland's young men, drunk with victory and the eyes of their dear tall girls. It did not occur to him—then—how the trek had nevertheless lasted for fifteen years, north and south, east and west, from Jutland down to the Balkan spine and back to the Belgic plains, from the orchards of Gaul to the gaunt uplands of Spain. And for all the burning towns and weeping new-caught women, all the men killed and all the gold lifted, the Cimbri had not found a home. There had been too many people, forever too many; you could not plow when the very earth spewed armed men up into your face.

"Well," said Ingwar. "Well, yes. Yes." He nodded his bushy head. "It's plain to see whose son you are. His youngest, perhaps, not counting the baseborn, but still son to Boierik. And that's something. Me, I am only a crofter, or will be when I get my bit of land, but you'll be a king or whatever they call it. So remember me, old Ingwar that bounced you on his knee back home, and let me bring my mares for your fine stallions to breed, eh?"

"Eh, indeed." Eodan slapped the broad back and went on into the camp.

The wagons were drawn up in many rings, the whole forming a circle bound together by low breastworks of earth and logs. It seethed with folk, there among the wheels. Even from his own height, Eodan could not see far across that brawl of big fair men and free-striding girls.

Here a band of boys whooped and wrestled at a campfire, while an old wife stirred a kettle of stew, naked towheaded children rolled in the dust, dogs barked and horses stamped. There a gang of men knelt about the dice, shouting as the wagers went, betting all they owned down to their very weapons—for tomorrow they would settle with Marius and own Rome herself. An aged bard, chilly even in summer, huddled into a worn bearskin and listened dumbly to the war-song of a beardless lad whose hands had already been bloodied. A youth and a maiden stole between wagons, seeking darkness; her mother shook her head after them in some bitterness, for it was not like the time when she was young—all this rootless drifting had ended the staid old ways, and no good would come of it. A thrall from the homeland, hairy and ragged, grabbed lumberingly for a timid lass stolen out of Gaul, and got a kick and a curse from the warrior who owned them both. A man whetted an ax against tomorrow's use; beside him snored three friends, empty wine cups in their hands. Here, there, here, there, it became one great whirl for Eodan, and the voices and feet and ringing iron were like the surf he had not heard in fifteen years.

He pushed his way through them all, grinning at those he knew, taking a horn of beer offered by one man and a bite of blood sausage from another, but not staying. Out there, alone in the night, he had remembered Hwicca, and it came to him that the night was not so long after all.

His own wagons stood near his father's, which were close to the god-cars. In two of these lived the hags who tended the holy fire, took omens and cast spells for luck—ugh, they looked like empty leather sacks, and it was said they rode broomsticks through the air. But another held the mightiest Cimbrian treasures, ancient lur horns and a wooden earth-god and the huge golden oath-ring. Eodan and Hwicca had laid their hands on that ring last year to be wedded. The Bull rode in the same wagon, but tonight Boierik had ordered it set in an open cart, that all might see it and be heartened. It was a heavy image, cast in bronze, with horns that seemed to threaten the stars.

They had wandered far, the Cimbri, and they had lost much of old habit and belief and belongingness. They were not even the Cimbri any longer. That was only the chief tribe of many which had joined their trek. There were other Jutes, driven from Jutland by the same succession of wild wet years when no harvest ripened and hail fell like knuckle-bones on Midsummer Eve. There were Germans gathered in along the way; Helvetians from the Alps and Basques from the Pyrenees, neighbors to the sky; even adventurous Celts, throwing in with these newcomers who so merrily ransacked all nations. They had no gods in common, nor did they care much for any gods; they had no high ancestors whose barrows must be sacrificed to; they had not even a single language.

Red Boierik and the Bull held them together. Eodan, with scant reverence for anything else, shaded his eyes in awe as he passed the green, horned bulk of it.

Then he saw his own wagon and his best horses tethered beside it. A low fire was burning, and Flavius was squatting above it, poking with a stick.

"Well," said Eodan, "are you cold? Or afraid?"

The Roman stood up, slowly and easily as a cat. He wore only a rag of a tunic, thrown him one day by his master, but he wore it like a toga in the Senate. Men had advised Eodan not to trust such a thrall—stick a spear in him, or at least beat the haughtiness out, or one day he'll put a knife in your back. Eodan had disregarded them. Now and then he would knock Flavius over with a single open-handed cuff, when the fellow spoke too sharply, but nothing worse had been needed; and he was more use than a dozen shambling Northern oafs.

"Neither," he said. "I wanted a little more light, to see the camp better. This may be my last night in it."

"Hoy!" said Eodan. "Speak no unlucky words, or I'll kick your teeth in."

He made no move against the Roman. War or the chase were one thing; beating those who could not fight back was another, a distasteful work. Eodan laid the whip on his thralls less often than most. Lately he had given Flavius the job, and the Roman had shown Roman skill at it.

"After all, master, I could have meant that tomorrow we will sleep in Vercellae, and a few nights thereafter in Rome." Flavius smiled, the odd closed-lipped smile with drooping eyelids that made Cimbrian men somehow raw along the nerves but seemed to draw Cimbrian women. In his mouth the rough, burring Northern language became something else, almost a song.

He was about ten years older than Eodan, not as tall or as broad of shoulder, but more supple. His skin was nearly as fair, though his hair curled black; his face was narrow, smooth, with wide red lips, but his jaw jutted, and his nose was curving chiseled beauty; his rust-colored eyes had lashes a woman might envy. Four years as a Cimbrian slave had put certain skills in his hands, but did not seem to have dulled his gaze or numbed his tongue.

Eodan gave him a hard stare. "If I were you, not tied to the wheel tonight and my fellows close by, I'd slip from here. You'd have a better chance of escaping now than you ever had before."

"Not a good enough chance," said Flavius. "Tomorrow you will win and I would be scourged or killed if caught. Or the Romans will win and I shall be released. I can wait. My folk are older than yours—you are a nation of children, but we are schooled in waiting."

"Which makes you less trouble to me!" laughed the Cimbrian. "You can be my overseer, when I build my garth. I'll even get you a Roman wife."

"I told you I have one. Such as she is." Flavius grimaced delicately. Eodan bristled. It meant nothing for Flavius to bed with thrall women—any man would do that if no better were to be had. The ugly, hardly understandable gossip about boys could be overlooked. But a man's wife was his wife, sworn to him in the sight of proud folk. Even if he did not get on with her, he was less than a man for speaking her name badly before others.

Well—

"What is the Roman consul's name?" went on Flavius. "Not Catulus, whom you beat at the Adige, but the new one they say has been given supreme command."

"Marius."

"Ah, so. Gaius Marius, I am sure. I have met him. A plebeian, a demagogue, a self-righteous and always angry creature who actually boasts of knowing no Greek ... indeed. His one lonely virtue is that he is a fiend of a soldier."

Flavius had murmured his remark in Latin. The Cimbric, the speech of barbarians, could not have been used to say it. Eodan followed him without much trouble; he had had Flavius teach him enough Latin for everyday use, looking forward to the day when he dealt with many Italian underlings.

Eodan said, "In my baggage cart you will find my chest of armor. Polish the helmet and breastplate. I would look my best tomorrow." He paused at the wagon. "And do not sit close to here."

Flavius chuckled. "Ah—I see what you have in mind. You are to be envied. I know all Aristotle's criteria of beauty, but you sleep with them!"

Eodan kicked at him, not very angrily. The Roman laughed, dodged and slipped off into darkness. Eodan stared after him for a little, then heard him strike up a merry melodious whistling.

It was the same air Gnaeus Valerius Flavius had been singing at Arausio in Gaul, to hearten his fellow captives. That was after the Cimbri had utterly smashed two consular armies, while Boierik was sacrificing all the prisoners and booty to the river god. Ha, but the hag-wagon had stunk of blood! Eodan had been a little sickened, as one helpless man after another went to be hanged, speared, cut open and brains dashed out—the river had been choked with the dead. He had heard Flavius singing. He did not know Latin then, but he had guessed from the kind of laughter (the Romans had laughed, waiting to be murdered!) that the words were bawdy. On an impulse he had bought Flavius from the river for a cow and calf. Later he had learned that he now owned a Roman of the equestrian class, educated in Athens, possessor of rich estates and tall ambitions, serving in the army as every wellborn Roman must.

Eodan went up two steps and drew aside the curtain in his doorway. This was a chief's wandering home, drawn by four span of oxen, walled and roofed against the rain.

"What is that?" The low woman-voice was taut. He heard her move in the dark wagon body, among his racked weapons.

"I," he said. "Only I."

"Oh—" Hwicca groped to the door. The dim light picked out her face—broad, snub-nosed, a little freckled, the mouth wide and soft, the eyes like summer heavens. Her yellow hair fell so thickly past the strong shoulders that he could hardly see her crouched body.

"Oh, Eodan, I was afraid."

Her hands felt cold, touching his. "Of a few Romans?" he asked.

"Of what could happen to you tomorrow," she whispered. "And even to Othrik.... I thought you would not come at all tonight."

His arm slipped down under the wheaten mane, across her bare back, and he kissed her with a gentleness he had never had for other women. It was not only that she was his wife and had borne his son. Surely it was not that she also came of a high Cimbrian house. But when he saw her it was like a springtime within him, a Jutland spring in lost years when the Maiden drove forth garlanded under blossoming hawthorns; and he knew that being a man was more than mere war-readiness.

"I went out to look at things," he told her, "and spoke with some men and with Flavius."

"So.... I fell asleep, waiting. I did not hear. Flavius sang me a song to make me sleep when I could not ... he had first made me laugh, too." Hwicca smiled. "He promised to bring me some of these flowers they have—roses, he calls them—"

"That is enough of Flavius!" snapped Eodan. May the wind run off with that Roman, he thought, the way he bewitches all women. I come back and the first thing I hear from my wife is how wonderful Flavius is.

Hwicca cocked her head. "Do you know," she murmured, "I think you are jealous? As if you had any reason!"

She withdrew. He followed, awkwardly taking off his clothes in the black, cramped space. He heard Hwicca go to Othrik, the small, milky wonder who would one day sit in his high seat, and draw a skin over the curled-up form. He waited on their own straw. Presently her arms found him.

II

The Cimbri met the joint forces of Marius and Catulus on the Raudian plain near the city Vercellae. It was on the third day before the new moon in the month Sextilis, which is now called August. The Romans numbered 52,300; no one had counted the Cimbri, but it is said each side of their army took up thirty furlongs and that they had 15,000 horses.

Eodan led a wing of these. He was not on one of the shaggy, short-legged, long-headed Northern ponies that had trotted across Europe—the tall black stallion he had found in Spain snorted and danced beneath him. He dreamed about herds of such horses, his own stock on his own land. He would raise horses like none the world had ever seen. Meanwhile he rode with silver-jingling harness to cast down Consul Marius.

His big body strained against a plate of hammered iron; his helmet carried the mask of a wolf, and plumes nodded above it; a cloak like flame blew from his shoulders; he wore gilt spurs on boots inlaid with gold. He shouted and bandied jokes—the lusty mirth of a stock-breeding people—with comrades even younger than he, shook his lance to catch the sun on its metal, put the aurochs horn to his lips and blew, till his temples hammered, for the joy of hearing it. "Hoy-ah, there, Romans, have you any word I can take to your wives? I'll see them before you do!" And the young riders galloped in and out, back and forth, till dust grayed their banners.

Boierik—huge and silent, scarred hawk face and grizzled red hair beneath a horned helmet, armed with a two-pronged spear—rode more steadily in the van of the army. And not all the Cimbri who marched after the horses owned so much as an iron head covering: there were many leather caps and arrows merely fire-hardened. Yet even some bare-legged twelve-year-old boy, wielding no more than a sling, might be wearing a plundered golden necklace.

The Romans waited, quiet under the eagles, their cuirasses and greaves, oblong shields and round helmets blinding bright in the sun. Among them waved officers' plumes and an occasional blue cloak, but they seemed as much less colorful than the barbarians as they seemed smaller—a dark short race with cropped hair and shaven chins, holding their ranks stiff as death. Even their horsemen stood rigid.

Eodan strained his eyes through the dust that was around him like a fog, kicked up by hoofs and feet. He could scarcely see his own folk; now and then he caught the iron gleam of chains by which the Cimbri had linked their front-line men together, to stand fast or die. He thought, with a moment's unease, that it aided the Romans, not to be able to see how great were the numbers they must face.... Then a war-horn screamed, and he blew his own in answer and smote spurs into his horse.

Hoofs drummed beneath him. He heard the wild, lowing du-du-du of the holy lur horns; closer now, the Romans tubas brayed brass and the Roman pipes skirled. He heard even the rattle of his own metal and the squeak of leather. But then it was all drowned in the Cimbrian shouts.

"Hau-hau-hau-hau-hoo!" shrieked Eodan into his horse's blowing mane. "Hau, hau! Hee-ee-yi!" So did we shout at Noreia, when Rome first learned who we are; so did we cry on the Alps, when we romped naked in the snow and slid down glaciers on our shields; so did we howl as we ripped up a forest to dam the Adige, break the Roman bridge and wring the eagle's neck! Hee-hoo!

It was a blink of time, and it was forever, before he saw the enemy cavalry before him. A shape sprang out of whirling gray dust, a shadow, a face. Eodan saw that the man's chin was scarred. He reached into his belt, whipped out one of his darts, and hurled it. He saw it glance off the Roman cuirass. He veered his horse to the right and shook his lance as he went by.

Around him it was all thudding and yelling. He only glimpsed the Roman charge, fragments through the dust, a helmet or a sword, once the eye of a horse. He leaned low in the saddle and reached for his second dart. The Cimbrian riders were moving slantwise across the advancing Roman front, and only those on the left actually met that charge. Eodan edged toward the fighting.

A mounted man loomed up, sudden as a thunderclap. Eodan threw the dart. It struck the Roman's horse in a nostril, and blood squirted out. The horse screamed and lunged. Eodan knew a moment of reproach; he had not meant to hurt the poor beast! Then he was upon the enemy. The fellow was too busy with his frantic mount to raise shield. Eodan drove his lance two-handed into the man's throat. He toppled from his seat, and the shaft was almost wrenched from Eodan's hands. With a single harsh movement, he freed it, nearly falling himself.

Another shape came out of the racketing dust. Eodan was able to see this one more clearly. He could have counted the iron bands of the cuirass or the iron-studded leather strips falling down the thighs above the kilt. He braced his lance in his hands and waited. The Roman came in at a trot. His shaft struck out. Eodan parried it, wood smote dully on wood. The horses snorted and circled while their riders probed. The Roman's steel hit Eodan's shield, where it hung on the Cimbrian's arm, and stuck there for a tiny moment. Eodan grabbed the lance with his left hand and shoved his own weapon forward, clumsily, with his right arm. The Roman's shield blocked him. Eodan whipped his shaft down like a club, and it hit the Roman's knee. The man yelped and dropped his shield. Eodan's iron went through his jaws. The Roman fell backward, dragging the lance with him, strangling in blood. His horse bucked, brought down a chance hoof and cracked the wood across.

Panting, Eodan drew his sword and looked about. He could dimly see that men were skirmishing through dust and heat—the Bull help us, but it was hot!—and that the battle was moving toward the Cimbrian right. Sweat runneled from him, stung his eyes and drenched his padded undergarment. He should have been crowing his victory. Two men slain for certain; it was not often you knew what a blow of yours had done. But he felt too choked in the dust.

He rode after the fight in search of an enemy. Boierik's plan had worked, to draw the Roman horse away while the Cimbrian foot struck their center. He could hear the screeches and hammering as men battled on the ground; he could not see it.

Slowly his mount gained speed. He was riding at gallop when he saw the knot of men. Two Romans ahorse were circling about four dismounted Cimbri, who stood back to back and glared. Eodan felt the heart spring in his breast. "Hee-ya-hau! Hau, hau, hau!" He whirled the great iron blade up over his head and charged.

The nearest Roman saw him and had time to face the attack. Eodan struck down, two-handed, guiding the stallion with his knees. The blow cried out on the Roman shield, and he felt it shock back into his own bones. He saw the shieldframe crumple. The Roman whitened and fell from the saddle, rolled over and sat up holding a broken arm.

The other one darted to his rescue. Eodan took a savage spear-thrust on his breastplate; it glanced down and furrowed his thigh. He reached out, hammering with his sword. It bounced on helmet and shoulder pieces, clamored against wood and steel. The lance broke across. The Roman rider sat firm, working his way in, shield upraised. Eodan hewed at his leg. The Roman caught the blow on his own sword, but the sheer force of it pushed both blades down. Eodan struck with the edge of his small shield and hit the Roman on the shoulder, knocking him from his saddle. The four dismounted Cimbri roared and rushed in.

A wolf-fight snarled by. Eodan followed it. All at once he found himself out of the dust cloud. The ground was torn underfoot, and a dead barbarian glared empty-eyed at a cloudless sky. Not many miles off gleamed Vercellae's white-washed walls. He could almost see how the townsfolk blackened them, standing and staring. If Marius fell, Vercellae would burn. High over all, floating like a dream, remote and lovely, were the snowpeaks of the Alps.

Eodan gasped air into lungs like dry fire. He grew aware that his leg bled ... and when had he been wounded in the hand? No matter. But he would sell his best ox for a cup of water!

His eyes went back to the battle. The cavalry skirmished in blindness. The Cimbrian foot raged against Catulus' legions, and Catulus buckled. Where was Marius?

Even as he watched, Eodan saw Roman standards in the dust, a gleam, a rippling steely line, and the army of Marius came from chaos and fell upon the Cimbri!

Eodan jogged back, scowling. It was not well. He could see how the barbarians were suddenly caught and chopped—and they had the sun in their eyes, and never had men fought in so much heat.... What had become of Boierik?

He entered the dust again. His tongue felt like a block of wood. Presently he found some of his young riders streaming back to the main fight. Their cloaks were tattered and their helmets stripped of feathers; one man's cheek gaped open, and his teeth grinned through.

"Hau-hau-hau!" Eodan gave the war-cry, because someone must, and hurled himself at the Roman lines. There was a whirling and a shock, and then the earth came up and struck him. His horse galloped off, a javelin in its flank.

Eodan cursed, rose to his feet and ran to the Cimbrian foot. Behind the chained first rank he saw men who were stabbing with spears, hewing with axes and swords, throwing stones and shooting arrows. They leaped into the air, howled, shook their tawny manes and rushed to do battle. The Romans stood firm, shield by shield, and worked.

Eodan reached the front-line flank of the Cimbrian host. He faced a dimly-seen foe; the sun in his brows blinded him almost as much as the dust and sweat. He heard a whistling, like the wind before rain, and felt three thumps in his shield. The Romans had launched their massed javelins.

Cimbri clawed at whetted iron in their flesh. Eodan was unhurt, but his shield was useless. What new trick was this? Only one metal pin left in the javelin head—it was bent and held fast by its crooked point; he could not wrench it free. He knew a chill. This Marius had thought of such a trick!

Casting his shield from him, Eodan joined the charge.

Elsewhere the invaders were already locked face to face with the enemy; now this part of their host met him. Eodan struck at a shield. His sword was blunted; it would not bite. A Roman blade flashed at him. He dodged it, planted his feet wide and hewed two-handed. A Roman helmet stopped his swing. He heard neckbones snap across. The man crashed to the ground. One behind him stepped into line. The legion advanced.

Gasping, Eodan retreated. It was a hailstorm of blows now—shouts, shocks, no more war-cries for lack of breath, but always the din of weapons. And the rising wildcat song of the pipes ... where were the lurs? No one blew the holy lurs? He yelled and struck out.

Backward step by step. His boot crushed something, the bones of a face. He looked down and saw it was Ingwar, with a Roman javelin in his armpit. He looked up again from the dead eyes, sobbed and hit through redness at a face above a shield. The Roman had a long thin nose like a beak. And he grinned. He grinned at Eodan.

Crash and clang and boom of iron. No more voices, except when a man hooted his pain. Eodan saw one of the linked Cimbri fall, holding his belly, trying to keep in his bowels. He died. His comrades dragged him backward. The man beside the corpse gasped—a slingstone had smashed his teeth—and sat down. A Roman took him by the hair and slashed off his head. Four Romans, close together, stepped into the gap and cut loose.

The battle banged and thundered under a white-hot sky. Italy's earth rose up in anger and stopped the nostrils of the Cimbri.

Eodan slipped and fell in a pool of blood. He looked stupidly at his hands, empty hands—where had his sword gone? Pain jagged through his skull. He looked up; the Roman line was upon him. He glimpsed the hairy knees of a man, drew his dagger and thrust weakly upward. A shield edge came down hard on his wrist. He cried out and lost the knife. The shield struck his helmet and darkness clapped down. The legionaries walked over him.

He sat up again, looking at their backs. For a little while he could not move. He could only watch them as they broke his people. There was a tuba being sounded. Was it in his head, or did it blow victory for Marius? His wrist was numb. Blood dripped slowly from a forearm gashed across.

At least he lived, he thought. The dead around him were thick. Never had he seen so many dead. And the wounded groaned until he sickened of their anguish. He sat there for a while longer. The field grew black with flies. The sun got low, a huge blood-colored shield seen through dust.

The Romans took the field, gathered themselves together and quick-marched after the fleeing.

Eodan struggled for wakefulness. He kept slipping back into night; it was like trying to climb out of a watery pit. There was something he must remember.... Was it his father? No, surely Boierik was dead; he would not outlive this day. He would fall on his own double-headed spear if he must. His mother had died two years ago, now let her ghost thank the earth Powers for that. And Hwicca—

It came to him. He reeled to his feet. "Hwicca," he croaked. "Othrik."

The Romans would take the wagon camp. They would take the camp. The Cimbri would be slaves.

Eodan lurched through nightmare across the Raudian plain. The hurt wailed at him. The gathering crows flew up as he passed and then settled down again. A riderless horse rushed past; he groped for its reins, but it was many yards away. The horizon seemed to shrink until it lay about him like bonds; then it stretched until he was the only thing that was; he heard the fever-hum of the world's brain under his feet.

When he neared the camp, miles beyond the battle, he had to rest for a while. His legs would carry him no more. He had some thought that there would be horses about; he and Hwicca and Othrik could get away. Oh, the wide cool Jutland moors! He remembered how the first snow fell in winter.

He saw the beaten Cimbri, such as lived, pouring into the camp. He got up again and stumbled among them. The Romans were already over the earthworks, briskly, like men who round up cattle.

Eodan went among them somehow. He saw the Cimbrian women stand in black clothes on their wagons, spears and swords in hand, screaming. They struck at their husbands and fathers and sons and brothers—"Coward! Whelp! You fled, you fled—" They strangled their own children, threw them under the wheels or the feet of the milling kine. Eodan passed a woman he knew who had hanged herself from the pole of a wagon, and her children were tied dangling at her heels.

Men who had thrown away their weapons, and saw the Romans gather in their folk, took what rope they could find. There were no trees here; they must tie themselves to the horns of the oxen, or by the neck to a steer's legs, to die.

The Romans worked hard, prodding prisoners into groups, stunning, binding. They took some sixty thousand alive.

Eodan paid small heed. It was happening elsewhere. He was a pair of feet and a pair of eyes, searching for Hwicca ... no more.

He found her at last. She stood beside the wagon that had been her household. She held Othrik to her breast and a knife in her hand. Eodan slipped, fell, picked himself up, fell again, crawled on hands and knees toward her. She did not see him. Her eyes were too wild. He had no voice left to call.

"Othrik," said Hwicca. Her words wavered. He could barely hear them above the noise. "Good Othrik." The hand with the dagger stroked across his fine pale-gold hair as he slept in the curve of her arm. "Be not afraid, Othrik," she said. "It is well. All is well."

A Roman squad came from beyond the god-cars. "There's a beauty!" Eodan heard one of them shout. "Get her!"

Hwicca sucked in a gasp. She laid the knife at her son's throat. The blade fell out of her fingers. Two of the Romans ran toward her. She looked at them at they neared. She picked up the baby by his ankles and dashed his head against the wagon boards.

"Othrik," she said numbly, and let the thing drop to earth.

The Romans—they were both young, hardly more than boys—stopped and gaped. One of them took a backward step. Hwicca went down on her knees and fumbled blindly after the dagger. "I am coming, I am coming," she called. "Wait for me, Othrik. You are too little to go down hellroad alone. I will come hold your hand."

The Roman squad was kicking some of Eodan's thralls toward the main slave group. Their officer looked over his shoulder at the two boys he had sent after Hwicca. "Snatch her up or she'll kill herself!" he barked. "You can't peddle dead meat!"

They broke into a run again. Hwicca's hand touched the dagger.

Flavius the slave sprang from behind the baggage cart. He put his foot on the knife. Hwicca stared like a clubbed animal up into his face. He smiled. "No," he said.

Eodan hitched himself forward another yard. She had not seen him, even yet. The two legionaries reached her, pulled her erect and hustled her off. Flavius went after them. Presently another Roman detachment came by and found Eodan.

III

Early the next year, only a few days after the feast of Mars had signaled the vernal equinox, they brought an injured slave to the master's house. This was on a Samnian latifundium owned by Gnaeus Valerius Flavius.

It was a raw day—low smoky clouds scudded over the fields, with a cold whistle of wind and a few rain-spatters. The rolling land lay wet and dark, its trees nearly bare save for a clump of pines. A rutted road gleamed with wind-ruffled puddles, and a few cows and goats, still winter-shaggy, huddled behind the sheds. The field slaves stamped their feet, blew on chafed hands and bent to their task; no idleness now, this was plowing and sowing time, that the flax might clothe Rome next winter. Their overseers rode up and down the lines, touching a back here and there with a skilled lash, but lightly; today the air did all the needful whipping for them.

Phryne came out of the house and felt how the wind bit. Her stola skirts streamed from her girdle, and she almost lost the blue palla before she got it on. Nevertheless, she could not have stayed another hour in the villa. Mistress Cordelia would have it hot as Ethiopia, and drown the brazier fumes in enough incense to throttle a mule!

As she walked over the sere lawn, smiling to old gardener Mopsus but hurrying on (he was a dear, and so lonely since the master sold his last grandchild—and a Greek—but how he talked), she saw two field hands approach. They were common dark men, some or other kind of barbarian, she didn't know what. But the one they supported was something else. She had not seen so big a man in a long time, and his unkempt yellow hair and beard tossed a blaze across the sunless sky.

Why ... he must be a Cimbrian ... one of the very people who had captured Master Flavius in Gaul! It was a Euripidean situation. Phryne went down the hill for a closer look. One of the dark men saw her and bobbed his head with coarse deference—a household slave, personal attendant to the mistress herself, was not common folks.

"What is the matter?" asked Phryne. "What happened?"

The Cimbrian lifted his head. He bore a strongly molded face, heavy about the jaw and brows but almost Hellenic of nose. His eyes were wide apart beneath a tattooed triskele (how had the yelping barbarians of Thule ever come on that most ancient symbol?) and a green color like winter seas. He was white about the lips. His left leg dragged.

"He got hurt by a bull," said the first of the dark slaves. "The big white stud bull broke out of the pen and come ramping down in the field. Gored one man."

"They didn't dare kill him," added the other. "He's worth too much, you see. And we couldn't lay a rope on him. Then this fellow got in, took him by the horns, threw him and held him down till help come."

Phryne felt how the blood flew into her face. "But that was wonderful!" she cried. "Another Theseus! And only hurt in the leg!"

The Cimbrian laughed, a short inhuman bark, and said: "I would not have been hurt at all—we used to throw bulls every year at the spring rites—but when those trained pigs of cowherds let him up they held the ropes too slack." His Latin was rough and ungrammatical, but it flowed quickly.

"Foreman says get him to the barracks and fix the bone," said one of those who upbore him. "Best we go."

Phryne stamped her foot. At once she realized that she had driven her small shoe into the mud. She saw the Cimbrian's eyes slide down, and a grin went like a ghost over his mouth. He looked back at her and nodded wryly. He knew.

She blurted in confusion: "Certainly not! I know what you would do, have that fool of a blacksmith splint it—and he will limp for the rest of his life. Up to the villa!"

They followed her, bashfully. No, not the Cimbrian—he jumped one-footed—but, when they entered the kitchen and put him in a chair, he sprawled as if he owned it. He was caked with mud, he had on only a sleazy gray tunic, there were shackle scars on his wrists and ankles, but he said, "Give me some wine," and the chief cook himself poured a full stoup. The Cimbrian emptied it in three long gulps, sighed, and held it out again.

Phryne went off after the house physician. He was Greek like herself, all the most valuable slaves were Greek, even as the only valuable free folk had once been—an aging man, with a knowledge of herbs and poultices to ease Cordelia, who suffered loudly and would not be without him. He came readily enough, looked at the wound, called for water and began sponging it.

"A clean break," he said. "The muscle was little torn. Stay on a crutch for a few weeks and it should heal as good as new. But first we'll hear some of those famous Cimbrian howls, for I must set it."

"Do you take me for a Southlander?" snorted the hurt man. "I am a son of Boierik."

"There are philosophers in my family," said the physician, with an edge in his voice. "Very well, then."

Phryne could not look at the leg, nor could she look away from the barbarian's face. It was a good face, she thought, it would be handsome in a wild fashion if some god would smooth off the slave-gauntness. She saw how sweat spurted out on the skin, when his bones grated, and how he bit his lip till the blood trickled.

The physician splinted and bound the leg. "I will see about a crutch," he said. "It might also be well to speak to the major-domo, or the mistress. Otherwise, if I know the chief field overseer, they'll put this man back at work before he is properly healed."

Phryne nodded. "You may go," she said to the gaping sowers. The cook bustled off on some errand. Phryne found herself alone with the barbarian.

"Rest a while," she said. She noticed his cup was empty for the second time; she risked the steward's wrath and poured him a third.

"Thank you." He nodded curtly.

"It was heroic of you," she said, more clumsy with words than she was wont.

He spat an obscenity. "The bull was something to fight."

"I see." She found a chair and sat down, elbows on knees, looking at her folded hands.

"What is your name?" he asked.

"Phryne." Though it meant nothing to him, she was obscurely grateful to hear no sniggering reference to her historic namesake's profession; why did they never remember that the first Phryne had modeled for Praxiteles, and forget what else she had been?

"I am Eodan, Boierik's son. Are you a Roman?"

She started, met a smoldering in his eyes and laughed a little. "Zeus, no! I am a Greek. A slave like yourself."

"A well-tended slave," he fleered. He was drunk—not much, but enough to loosen the wariness learned in the dealers' pens. "A darling of the house."

Anger leaped in her—it stung that he should snap when she had offered only help—and she said, "Are you so brave to make war on me with your tongue?"

He checked himself. As he sat rubbing his shaggy chin, she could almost see him turning the thought over in his mind. Finally, pushed out with an effort that roughened it: "You are right. I spoke badly."

"It is nothing," she said, altogether melted. "I think I understand. You were a free man. A king, did you say?"

"We have ... we had no kings," he mumbled. "Not as you seem to mean the word here—what little I've heard. But truly I was a free man once."

A gust of rain went over the tiled roof. The hearthfire leaped and sputtered; smoke caught Phryne's eyes, and she coughed and threw back her cloak. Eodan's gaze fixed on her.

She knew that look. Every woman in the Roman world knew it, though the high-born paid it no heed. A slave girl must. It was the look of a man locked away from all women for months and years, lucky to have a rare hurried moment in a strawstack at festival time. The penalty for attacking expensive female property could be death, if her owner cared (Phryne doubted Cordelia would) ... still, a desperate hand might seize her one night. She stayed close to the villa when she was here.

She said quickly, "I have heard Master Flavius telling he was a prisoner among your folk for four years."

Eodan laughed, deep laughter from full lungs, but somehow grim. At last he answered, "Flavius was my slave."

"Oh—". A hand stole to her lips.

Still he looked at her. She was not tall, but she was lithely formed. The simple white dress fell about long slim legs, touched the curve of thigh and waist, drew over small firm breasts. Her hair was of deep bluish-black, piled on a slender neck and caught with a bone fillet. Her face did not have classic lines; perhaps that, and her quietness when Roman men were about, was why she remained a virgin at twenty. But more than one lovesick slave had tried to praise deep violet eyes, smoky-lashed under arching brows, a wide clear forehead, tilted nose and delicate chin, soft mouth and pale cheeks.

Eodan lifted his cup. "Be not afraid," he said. "I cannot leave this chair before they bring me a staff."

Phryne received his bluntness with relief. Some of the educated household men simpered about so she could vomit. She could give no better reason, in all honesty, for not taking a lover or even a husband. Cordelia had not forbidden her, and the memory of a certain boy was chilly comfort.

"I should think," she whispered, leaning close lest it be overheard, "that if you treated Flavius kindly—and he did not look much abused when he came back—he could have found something better for you than field labor. That destroys—" She stopped, appalled.

Eodan said bleakly, "Destroys men. Of course. Do you think I have not seen what a few years of it do to a man? He could have done worse, I suppose—resold me to the games I hear tell of, or as a rower on a ship. But he could never trust me running about a house, even another man's house, as freely as you do."

"Why not? You can have no more dreams of escape. You have seen crucified men along the roads."

"Some things might be worth a crucifixion," said Eodan. He made no great point of it; his tone was almost matter-of-fact, wherefore Phryne shuddered.

"Hercules help me, why?" she breathed.

Eodan said from a white face, "He took my wife."

He drained his cup.

Phryne sat very still for a while. The wind mourned about the house, wailed in the portico and rubbed leafless branches together. Another rain-burst pelted the roof.

"Well!" said Eodan at last, "Enough of that, little Greek. I should not have said anything, but for the wine, eh, and this leg feels as if there were wolves at it." The arrogance slipped from him and she looked into eyes hurt and helpless, which begged her to leave him his last rags of pride. "You will not speak of what I said?"

"I swear so," she answered.

He regarded her for a very long while. Finally he nodded. "I think I can believe that," he said.

Steps sounded on the brick floor. Phryne stood up, folding her hands before her and casting duly meek eyes downward. Eodan remained as he was, his gaze challenging those who entered. They were the major-domo and Mistress Cordelia.

The major-domo, an Illyrian grown fat and bald in his own self-importance till he could imagine nothing more than accounts and ordering other slaves about, said: "Here the Cimbrian is, I am told, my mistress. I shall call porters and have him carried back down to his barracks."

Cordelia said: "Wait. I told you I would like to speak with this bull wrestler."

Phryne raised her eyes, suddenly afraid for Eodan. He was so proud, too much so for his own good. Slaves whom the dealer failed to break inwardly, so that they let him chain their spirits as well as their hands, might sometimes rise high and even regain freedom; but they were more likely to end on a cross or in the arena. And Eodan was drunk and—O sea-born Cyprian—he was looking at his owner's wife as he had looked at her!

"You are a bold man," said Cordelia.

Eodan nodded.

She laughed. "And not overburdened with modesty," she went on. "Do not tell me we have another of these barbarian kings!"

Eodan replied: "If you are Flavius' wife, then we have your husband's one-time owner."

Phryne's heart seemed to crash to a halt. She stood for a brief space feeling blood drain from her. Now the gods would have their revenge, when a man bore his head so high.

Cordelia stepped back. For a moment she flushed.

She was a tall woman of Etruscan stock, perhaps descended from Tarquin himself and some jewel of Tarquin's harem. Thirty years old, she had the fullness of body that would turn to fat in another decade but was as yet only superb. A silken dress violated every sumptuary law the Republic had ever passed to emphasize hip and bosom, insolently. Her hair was thick, its black copper-tinged, her face curve-nosed and heavy-lipped, her eyes like southern nights. She had the taste to wear only one ornament, a massive silver bracelet.

The major-domo turned red and gobbled his indignation. Cordelia glanced at him, back at Eodan, then suddenly she laughed aloud.

"So this is what he looks like! And my husband, who has wearied Roman dinners this half a year with his stories of the Cimbri, did not bring you to show off!"

She paused, looked closely into Eodan's face—their eyes met like swords—and murmured, "But I see why."

Phryne leaned against the wall; she did not think her knees would hold her unaided. Now they were on a well-marked path; she knew what came next. The final fate of Eodan was hidden—it could be gay or gruesome, but this part of the way was mapped.

Young Perseus had entered the Gorgon's lair and come back alive.

She wondered why she felt like weeping.

IV

"He has deserved well of us," Cordelia said. "Let him be kept in the household, at least till he is properly healed. Give him good raiment and light work. And first of all a bath!"

Thereafter she did not hurry matters. Eodan limped about with a crutch, ate and drank and slept enormously, scoured pots or helped old Mopsus the gardener. He spent much time down at the stables, where he soon had the friendship of the head groom, a dour Cappadocian who was believed to have been hatched rather than born since not even a mother could have loved him. Phryne did not understand how a man of intelligence—and Eodan had a good mind in his rough way—could sit hour after hour talking about currycombs and fetlocks and spavins and whatever else there was; but so it went and, after all, divine Homer dwelt lovingly on horses.

Washed, shaved, his hair cut and combed, a white tunic and sandals on him, Eodan might almost have been a Homeric warrior himself—Diomedes, perhaps, or Ajax the haughty. As he grew rested and fleshed out, his manners became milder, he snarled or cuffed at men less often, his smiles were sometimes nearly warm instead of a mere wolfish baring of teeth. But he dropped his green eyes for no one, and the house slaves who shared their room with him were kept at a frosty distance.

The major-domo was afraid of him. "I would not trust that barbarian, not one inch," he told Phryne. "My dear, you should have seen his back when he first bathed. I would not even try to count all the whip scars. And many slashes were new—he got them here, in the months we have had him, the last of them perhaps only yesterday! Mark my words, it is the sign of an unruly heart. It is such men who lead slave revolts. If he were mine, I would geld him and sell him to the lead mines."

"Some men were born gelded," said Phryne coldly, and left. She could almost see the crisscrossing of thin white lines on Eodan's shoulderblades. She avoided him for a while, uncertain why she did so.

And the springtime waxed. Each day the sun stood higher; each day a new bird-song sounded in the orchard. One morning fields and trees showed the finest transparent green, as if the goddess had only breathed on them in the night. And then at once, unable to wait, the leaves themselves burst out and the orchard exploded in pale fire.

It happened Cordelia was complaining of a headache again; she must lie in a dark room and make everyone creep by. Phryne, who considered her mistress as strong as a cow, found an excuse to leave the villa. She would gather apple blossoms and arrange them for Cordelia's delight.

The morning was still wet, after a short rain. Where the sun struck the grass, it flashed white. A thrush sat on a bough and chanted of all bright hopes; a milk cow grazed in a meadow, impossibly red. When Phryne went among the gnarled little trees, they shook down raindrops upon her. She took a low branch in her arms and buried her face in its flowers.

"Poor blooms," she whispered. "My poor babies. It is wrong to take away your springtime."

The knife bit at the twigs; she filled her arms with apple blossoms.

Eodan came from the villa. He crutched along as readily as a three-legged dog, bound for the stables carrying a mended bridle. The endlessly gossiping slaves had told Phryne the barbarian was clever with his hands.

But when he saw her he halted. He had never thought much about beauty—land, workmanship, live flesh was good or bad, no more. Now, briefly, the sight of a girl's dark head and slim waist, with dew and white radiance between, went through him like a spear.

The moment passed by. He thought only as he swung about toward her that—by the Bull!—it was a new year and she was a handsome wench. "Ave," he called.

"Atque vale," said Phryne, smiling at him. His hair needed cutting again, and it was uncombed, tangled with sunlight.

"Hail and farewell? Oh, now, wait!" Eodan reached her and barred the path. "You have no haste. Come talk to me."

"My task here is finished," she said in a quick, unsure voice.

"Must they know that?" Eodan's coldest laugh snapped out. "I've learned how to stretch an hour's task into a day. You, having been a slave longer, must be even more skilled at it."

The fair planes of her cheeks turned red. She answered, "At least I have learned not to insult those who do me no harm."

"I am sorry," he said, contrite. "My people were not mannered. Is that why you have kept yourself from me?"

"I have not," she said, looking away. "It—it only happened ... I was busy—"

"Well, now you are not busy," he said. "Can we be friends?"

The gathered blossoms shivered on her breast. Finally she looked up and said, "Of course. But I really cannot stay here long. The mistress has one of her bad days."

"Hm. They say in the kitchen that's only from idleness and overeating. They say her husband sent her down here because her behavior made too much of a scandal even for Rome."

"Well—well, it was a—a rest cure...."

Ha, thought Eodan, I would like to help Mistress Cordelia rest her tired nerves! The story went that Flavius needed her family's help too much in his political striving to divorce her. And, if ever a man deserved the cuckoo sign, it was Flavius!

Eodan clamped on that thought and tried to snuff it out. He could taste its bitterness in his throat.

He said: "You have a Cimbrian habit, Phryne, which I myself was losing. You do not speak evil of folk behind their backs. But tell me, how long have you been here?"

"Not long. We came down perhaps a week before your accident." Phryne looked past a stile, over the meadow to the blue Samnian hills. Tall white clouds walked on a lazy wind. "I only wish we could stay forever, but I'm afraid we will go back to the city in a few months. We always do."

"How do you stand with the mistress?" asked Eodan. He hitched himself a little closer to the girl. "Just what is your position?"

"Oh—I have been her personal attendant for a couple of years. Not a body servant; she has enough maids."

Eodan nodded. His thoughts about Cordelia's younger maids were lickerish, and their eyes had not barred him. But so far there had been no chance. He listened to Phryne:

"I am her amanuensis. I keep her records and accounts, write her letters for her, read and sing to her when she wants such diversion. It is not a hard life. She is not cruel. Some matrons—" The girl shivered.

"You are from Greece?"

She nodded. "Plataea. My grandfather lost his freedom in the war of—No matter, it would mean nothing to you." She smiled. "How tiny our vaunted world of Greeks and Romans is, after all!"

"So you were born a slave?" he went on.

"In a good household. I was educated with care, to be a nurse for their children. But they fell on evil times two years ago and had to sell me. The dealer took me to Rome, and Mistress Cordelia bought me."

He felt a dull anger. He said, "You wear your bonds lightly."

"What would you have me do?" she replied with a flash of indignation. "I should give thanks to Artemis for a situation no worse than this—my books, at least, and a measure of respect, and an entire life's security. Do you know what commonly happens to worn-out slaves? But my mind will not wear out!"

"Well, well," he said, taken aback. "It is different for you." And then wrath broke loose, and he lifted his fist against heaven. "But I am a Cimbrian!" he shouted.

"And I am a Greek," she said, still cold to him. "Your people did not have to come under the Roman yoke. You could have stayed in the North."

"Hunger drove us out. We were too many, when the bad years came. Would you have us peaceably starve? We did not even want war with Rome, at first. We asked for land within their domains. We would have fought for them, any enemies they wished. We sent an embassy to their Senate. And they laughed at us!" Eodan dropped the bridle, leaned against his crutch and held out shaking claw-curved fingers. "I would tear down Rome, stone by stone, and flay every Roman and leave their bones for ravens to pick!"

She asked in a steel-cool tone: "Then why do you think it evil of them to do likewise to you, since the gods granted them victory?"

He felt the tide of his fury ebb. But it still moved in him; and the ocean from which it had come would always be there. He said thickly, "Oh, I do not hate them for that. I hate them for what came afterward. Not clean death, but marching in a triumph, shown like an animal, while the street-bred rabble jeered and pelted us with filth! Chained in a pen, day upon day upon day, lashed and kicked, till we finally went up on a block to be auctioned! And afterward shoveling muck, hoeing clods, sleeping in a hogpen barracks with chains on, every night! That is what I have to revenge!"

He saw how she shrank away. It came to him then that he had his own purposes for her. He forced a stiff smile. "Forgive me. I know I am uncouth."

She said with a break in her voice, "Were you put on the block? Did it only happen that Flavius bought you?"

"Actually, I was not," he admitted. "He had inquiry made for me, and bought me directly. He saw me and said with that smile of his that he wanted to be sure of my fate, so he could pay me back the right amount of both good and evil. Then I was walked down here with some other new laborers."

"And your—" She stopped. "I must go now, Eodan."

"My wife?" He heard his heart knocking, far away in a great hollowness. "He told me that he had Hwicca, too—in Rome ..."

His hands leaped out. He seized her by both arms so she cried out. The apple blossoms fell from her grasp, and his foot crushed them.

"Hau!" he roared. "By the Bull, only now do I think of it! You attend the mistress? And she still shares her husband's town house? Then you have seen Flavius in Rome this winter! You have seen her!"

"Let me go!" she shrieked.

He shook her so her teeth rattled. "How is she? You must have seen her, a tall fair girl, her name is Hwicca. What has become of her?"

Phryne set her jaws against the pain. "If you let me go, barbarian, I will tell you," she said.

His hands dropped. He saw finger marks cruelly deep on her white skin. She touched the bruises with fingers that trembled while tears ran silent down her face. She caught her lip in her teeth to hold it steady.

"I am sorry," he mumbled. "But she is my wife."

Phryne leaned against the tree. At last she looked up, still hugging herself. The violet eyes were blurred. She whispered, "It is I who must ask pardon. I did not realize it was the same—I did not know."

"How could you have known? But tell me!" He held out his empty hands like a beggar.

"Uicca ... I saw her once in a while. The Cimbrian girl, they all called her. She seems well thought of by Flavius. He keeps her in a room of her own, with her own servants. He is—often there. But no one else sees her much. We never spoke. She was always very quiet. Her servants told me she was gentle to them."

"Flavius—" Eodan covered his eyes against the unpitying day.

Phryne laid a hand on his shoulder. It shuddered beneath her palm. "The Unknown God help you," she said.

He turned around and looked upon her, then reached out and gathered her against him. He kissed her so her mouth was numb.

She writhed free, scraped down his ankle with a sandaled foot and clawed with her nails until he let her go. She was white; her loosened dark hair fell about her like a thunder-cloud.

"You slobbering pig!" she cried. "So that is all you miss of your wife!"

She spun about and ran.

"Wait!" he cried. "Wait, let me tell you—I only—"

She was gone. He stood upon the fallen blossoms and cursed. Hwicca would have understood, he thought in wrath and desolation; Hwicca is a woman, not a book-dusty prune, and knows what the needs of a man are.

He looked down, and up again, and finally north, toward Rome. Then he picked up the bridle and went on to the stables. That day he contrived to be given a task at the forge, shaping iron, and the courtyard rang with his hammerblows until dark.

The days passed. The flax was sown. They paid less heed to the ancient festivals now than formerly; once these acres had belonged to free men; now it was all one plantation staffed with slaves. But some custom still lived. The week of the Floralia was observed, not as immoderately as in Rome, but with a degree of ease and a measure of wine.

On the day before the Floralia the physician examined Eodan's leg. "It has knit," he grunted. "Give me back my crutch."

Eodan asked wearily, "Will they return me to the fields?"

"That is not my province." The physician left him.

Eodan walked slowly out of the villa into the walled flower garden behind the kitchen. His leg felt almost a stranger to him. No matter, he would be running in an hour. Running hence? They were not going to make a field hand of him again! It ground away, not only the body, but mind and pride and hope, until a mere two-legged ox remained.

Phryne was talking with one of Cordelia's maids. She saw him and said, "Enough. Come with me." The girl's eyes lingered on Eodan as she went by. He swore at Phryne; in all the time since the orchard morning, she would not speak to him—the winds take her! He considered how to get the maid alone.

"There you are! And well at last! You've been loafing too long, you lazy dog, and eating like a horse the while! Come here!"

Eodan strolled toward the major-domo. He rubbed his fist, looked at it and back at the man's nose, nodded and said: "I did not hear you. Would you repeat your wish?"

"There, there are some—heavy barrels to move," stammered the major-domo. "If you will kindly come this way ..."

Eodan was willing enough to trundle the wine casks about. It was a glory to feel his strength returned. And the villa was all in a bustle—they were hanging up garlands everywhere, the girls giggled and the men laughed, o ho ho, tonight! Eodan drew a pretty wench, a maid, into a corner, they scuffled a little, she whispered breathlessly that she would meet him in the olive grove after moonrise or as soon as she could get away....

The Roman correctness of household eased. Men helped themselves openly to wine, laughed with their overseers, drew buckets of water to pour over sweaty skin, combed the fleas from their hair and wove garlands. Eodan, rolling a great cheese from the storehouse, chanted a Cimbrian march for his friend the groom.

But no one understood the words.

At sundown the lamps were lit with those sulfur-tipped sticks Eodan still thought a rash risk of Fire's anger. The villa glowed with a hundred small suns of its own. He stood in the garden with Mopsus. "I must go in now and help feed my fellows," he said.

"So, so. A good feed tonight. A good feed. My granddaughter used to live for Floralia night—or was it my daughter, she was a baby too, once ... I wonder, though, why Mistress hasn't asked any high-born guests. It isn't like Mistress not to have fun when she can."

Eodan shrugged. He had seen Cordelia often enough, seated on a couch or borne in a litter, but his world had been far from here, even in the house; she rarely entered the kitchen or the stables. She was only a task his little maidservant must finish before joining him under the olive trees.

He went back into the villa. At its rear were the rooms where the household's male property ate and slept. As he passed out of the kitchen toward those chambers, he saw Phryne.

The lamp that she held turned her pale skin to gold. He moved forward, smiling, a little tipsy, meaning only to explain himself to her. She lifted her hand. "Stop."

"I'm not about to touch you," he flared.

"Good!" Her mouth twisted upward. He had seldom heard so whetted a voice. "I was sent to fetch you. Come."

She turned about and walked quickly toward the atrium. He followed. "But Phryne, what is this?"

Her fist clenched. "You do not know?"

He halted and said harshly, "If I am about to be sent back to the barracks—"

She looked over her shoulder. Tears stood in her eyes. "Oh, not that," she said. "Be not afraid of that. Be glad! You are about to be honored and pleasured."

"What?"

"In fact, the highest honor and the noblest pleasure of which you are capable." She stamped her foot, caught her breath and strode on. He followed in bewilderment.

They crossed an open peristyle, where the first stars mirrored themselves shakenly in a mosaic pool. Beyond was a door inlaid with ivory, Venus twining arms about beautiful Adonis. A Nubian with a sword stood on guard. Eodan had seen him about—a huge man, cat-footed, but betrayed by his smooth cheeks and high voice.

Phryne knocked on the door. "Go in," she said. "Go on in."

Someone giggled, down in the flickering darkness of the corridor. Eodan pushed his way through, and the door swung shut behind him.

He stood in a long room, marble-floored, richly strewn with rugs and with expensive furnishings. Many lamps hung from the ceiling, till the air seemed as full of soft light as of incense. The window was trellised with climbing roses.

A table bore wine and carefully prepared food for two. But there was only one broad couch beside it.

Cordelia was stretched out on the couch. Light rippled along her gown. It was of the sheerest silk; her flesh seemed to glow through. She sat up, smiling, so that her copious breasts were thrust at him. "Hail, Cimbrian," she said.

Eodan gaped. The blood roared in his temples.

She stood up, took a big two-handled silver cup and walked across to him. Her gait was a challenge. When she stood before him he could look down the loose open front of her dress. "Will you not drink with me?" she asked.

"Yes," he said, in his own tongue, for Latin had no such simple way of agreeing. He took the goblet and hoisted it in hands that shook. He was no judge of wine, nor would he have cared tonight, but he noticed dimly that this was smooth and strong.

"I have watched you go about," said Cordelia. "I wanted to thank you for your—services—but it seemed best to let your wound heal first. And then today I saw you lift a cask I would have set two men to carry. I am very glad of that."

He handed her back the cup, still mute. "All of it?" she laughed. "But I wanted to share it with you. As a pledge of friendship. Now we must pour another."

Her thigh brushed his as she turned. He gulped for air. "Come," she said, took his hand and led him to the couch.

The flask gurgled as she poured from it. "My husband was wrong to set a king to work in his fields," she went on. "For I will not believe you were anything less than a king of your people. Perhaps we two can reach a better understanding—for a while ..." She looked up at him, slantwise. "It will depend on you, largely." She lifted the beaker again. "To our tomorrows. May they be better than our yesterdays."

They drank in turn. She sat down and drew him beside her. "I have tried and tried to pronounce that barbarous name of yours," she said. "I will give you another. Hercules? Perhaps!"

Suddenly her mouth was hot upon his.

She stood up, breathing heavily. "I meant to eat first," she said, quick slurred words through curling sweet smoke. "It would be leisurely, civilized, with much fine play. But that would be wrong with you, I see that now." She reached out her arms. "Take off your tunic. Take off my gown. Let us keep the Floralia."

Much later, when the wine and the food were gone, the lamps burned out and the first thin gray creeping into the eastern sky, she ruffled his hair and smiled sleepily. "I will surely call you Hercules."

V

After festival time, the latifundium went back into harness. Up in the villa there was the measured pace of days—housework, garden work, much dawdling until some overseer went by, backbiting gossip, petty intrigues for women and position, sometimes after dark a furtive Asiatic ritual of magic or mystery. A womanish world. Eodan considered himself well out of it.

But riding through the fields, where the sun and the whip blistered a hundred naked backs and all a man's dreams finally narrowed to the day's hoeing and the night's shackled sleep, Eodan wondered with a chill how he had remained himself even for those few months he served. Winter had helped—days on end where he sat idle with the others, dozing, cracking fleas, once or twice knocking a tooth out of someone who offered him loathsome consolations.... Nevertheless, he searched himself as no Cimbrian had done before and knew that his servile time had indeed touched him. He went more warily through life, slowly learning how to guard his words. He would never again live wholly in the moment's joy; he would always be thinking beyond—where would the next attack come from, or how should he himself attack?

Even when Cordelia taught him some new pleasure—and she had given her life to such arts—a part of him wondered how long this would endure. For the rest, however, it had been a good month, or whatever time had passed. He had the name of bodyguard, though only the surly Nubian was allowed to bear weapons. He accompanied her on impulsive journeys about the countryside, organized hunts in the forests for her to watch, matched himself in athletic exhibitions with the brawnier slaves from this and surrounding farms. A few times she even sent him on errands of two or three days, as to a town to arrange for certain supplies. He thought of using the chance to escape—but no, he knew too little of Italy; they would snare him and tie him up to die. Wait a little longer, make careful plans, or even win freedom for himself and Hwicca within this Roman world. It was not impossible, given patience.... Meanwhile, aloneness with a blooded horse, among hazy hills and through woods where only dryads and charcoal burners dwelt, was a gift to him, almost like being free again.

Now he was coming back from such a trip. He rode at an easy mile-eating pace, soothed by hoof-plop and saddle-squeak, the breeze in his face amid the clean summery odor of his mount. He was richly clad; his tunic, cloak, and boots were of simple cut and muted color, but he liked the sensuous fabrics. His hair fluttered in the light wind, and he sat straight as a lancer; and, when he saw the villa itself, dark against a sky turning pink and gold with sunset, he was close to letting out a Cimbrian whoop. After all—Cordelia! He checked the noise and merely grinned instead, but he set the horse to a gallop, and they came ringing and snorting into the rear courtyard.

"Hoy-ah!" Eodan jumped to the flagstones, tossed his reins at a stableboy and strode quickly toward the garden gate. The shortest way to the atrium was through the roses.

As he passed into their fragrance, he stopped. Phryne was alone between the walls, gathering a few early blooms. A great cloud of hot bronze lifted far, dizzyingly far above her head; the sky beyond it was taking on the color of her eyes.

"Hail," he said.

She straightened herself. The plain white stola fell in severe folds, but could not hide a deerlike grace. She had not Cordelia's opulence, and she barely reached to his heart; yet it came to him that he had never thought of her as boyish, nor as just a little bit of a thing.

Her face, all soft curves and a few pert, nearly rakish angles, stiffened. She turned as if to go, but resolve came back; she continued her work, ignoring him.

He did not know why, unless it was that his small journey had given certain unseen chain-galls time to heal, but he went toward her and said, "Phryne, if I have wronged you, how can I mend it unless you tell me what I did?"

Her back was turned, her head bent. Under the softly piled black hair, he saw that her nape was still almost childish. Somehow that filled him with tenderness. She said, so low he could scarcely hear it, "You have not harmed me."

"Then why have you circled so wide of me? You never answered when I greeted you in passing. You have said me no word in weeks."

Her voice rose a little but shook: "Well, some women may be glad of your pawing. I was not!"

Eodan felt himself flush, as deeply as the western sky. He responded clumsily, "Why have you given me no chance to say what I meant? It was wrong of me to—to kiss you. I ask your pardon. But I was driven; there was a Power in that place—and did I hurt you so much?"

Then she looked up at him and said in a tone heavy with unshed tears: "It was chiefly yourself you harmed."

Eodan looked away. For a moment he trod from her, up and down a graveled path that mumbled beneath his feet. The bronze cloud cooled toward newly blown roses. In the west, just above the crumbling vine-covered wall, he could see a green streak, unutterably clear. Somewhere a cow lowed; otherwise it was very quiet.

Eodan said at last, slowly, word by word, as he hammered it into shape within himself: "I understand. But you do not understand me. They say you are still a maiden. Well, you have called a curse on me for doing something of which you have no knowledge."

Phryne's fingers clenched about a rose stalk. The thorns bit. She stared at the bright blood drops, wiped them on her gown in a blind fashion and said through unfirm lips: "Perhaps it is true. I thought one thing of you. When you did something else, that is how you hurt me. But perhaps I have indeed not understood."

"I am not wont to speak of these matters," he told her, with effort. "Among the Cimbri, it was not so—so twisted together. Wives did not betray their husbands. Husbands—well—a man is otherwise than a woman. He has other needs. I was driven by the Powers of earth; the Bull was within me that day, Phryne. And more than that—Can you understand how it felt to hear you tell what has—has become of my wife, the mother of my son, whom she killed to keep him free? Can you understand how I would turn for any—what is the word?—any comfort that you could give—or anyone could—Do you see?" he pleaded, facing her with his hands outspread.

She rubbed her eyes. "I see," she whispered.

He doubled up one fist and smote it softly into the other palm, again and again. "It would help Hwicca not a bit if I let the Bull roar within me so loud I could think of nothing else," he said. "Indeed it was a new thought to me, this you bring forth—that what is between a man and his wife, for good or ill, can in any way be changed by whether he sleeps alone or not when she is gone."

"I am not so sure of that," she answered. "No man will say it is true of her!" When she lifted her face, he saw it was streaked with silent tears. "But I could be wrong. I do know little of these matters."

Eodan said, with a sad smile tugging up one corner of his mouth, "Between the time I wed Hwicca and the time a year afterward, when we came to the Raudian field, I touched no other woman. It was not that I lacked the chance, but only that none seemed worth the time I could be with her. Will you believe that?"

She nodded dumbly.

"Well, then." Eodan held out his hand, in the manner he had learned from the Romans. "Shall we be friends?"

She caught it tightly. Sunset smoldered to dusk. He could see her as little more than a paler shadow.

She said at last, in a tone gone remote from sorrow, "I would not have you think, Eodan, that I ever condemned you because of some dead philosopher's thoughts on chastity. It was that I believed your case was like mine. I have been lonely too, now and then. But I see it was a false hope. No man, no woman ever has the same destiny; we are all pursued by our private Furies. Help me remember that, Eodan!"

He asked her, out of a newly reborn pain, "What happened, Phryne?"